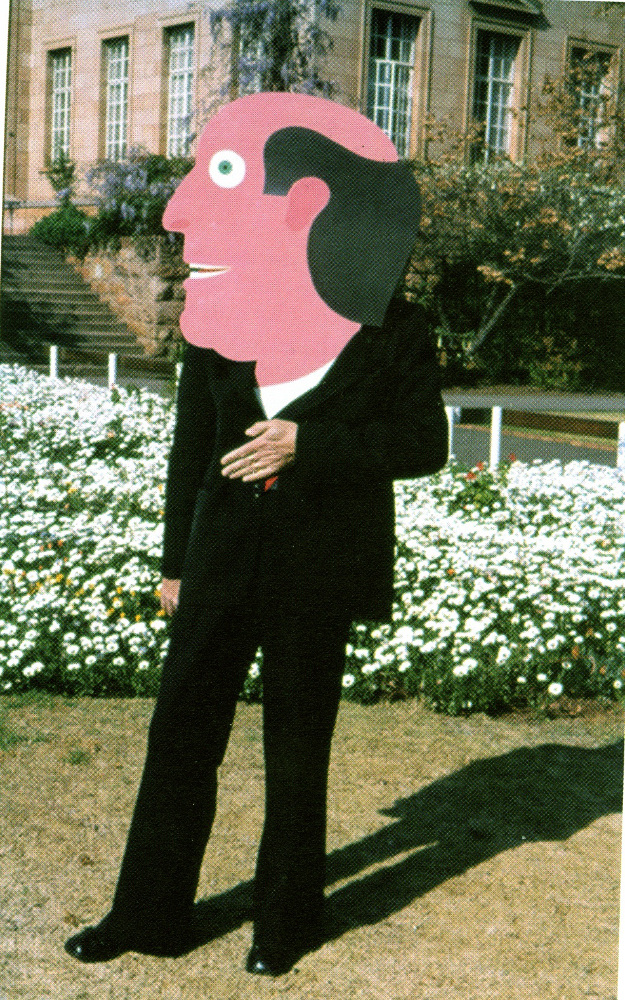

Pancho Guedes.

Grief is an intensely personal thing. We all feel it differently and we all express it in our own ways. And yet, when the person who died is Pancho Guedes — architect, philosopher, artist and creator — the grief exists not just in the personal space but is owned by the many his life touched.

Since Pancho’s death on Saturday morning — holding my aunt Kitty’s hand and looking at a portrait of his beloved wife, my grandmother Dori – we have felt the love and support of a global network of his friends, associates, ex-students and admirers. All forged a personal connection with Pancho and all feel his loss keenly. It helps. It helps to not be so isolated in our grief and to feel that so many understand what has been taken from us.

I am not an art historian or an architect. My admiration for my grandfather was not based on his incredible intellect or his astounding creativity — these were simply a facet of his existence. I loved him as a grandfather, but it’s not possible to have a grandfather like that without his brilliance the creativity intersecting with everyday life.

The garden of my grandparents’ house in Melville was lined with wooden totem poles of trains charging skyward. When, one summer, a woodpecker made its home in the intricate sculptural work, my grandfather wasn’t dismayed. Rather, he put up a stepladder and encouraged me to climb the pole up to peer at the nest.

Pancho wasn’t a purist. He accepted that his architecture had a life of its own and would be appreciated and adapted by the people – and woodpeckers – who made their homes in it. These are his words:

When is the building most real?

When it is a bunch of ideas?

A rough scribble?

When it is many sheets of municipal linen prints?

Is it when the bones are up?

When the plastering is done?

When the owners move in?

When it catches fire?

Or when the first owners move out?

Is it not real exploding?

Is it real riddled and shattered by bullets?

Or faked new by a new owner?

Or with broken window panes, haunted, in a wild and overgrown garden – a young gang’s clubhouse?

He lived surrounded by his creations. He didn’t make art to sell but for himself, perhaps as a counterpoint to the architectural work he did for clients – though I doubt he was ever bound by anyone else’s sensibilities. I’ve heard stories of clients listing their priorities, then being presented with plans that were nothing like they envisaged, and yet, on reflection, were everything they had hoped for.

The doll’s house he made “for Kitty” was suspended on the wall of his office by the time I came along. He lived surrounded by a friendly chaos of books and art and objects. I was allowed to play with treasures at his feet while he worked: fertility figurines from around Africa, bits and pieces from ancient Roman digs, a moonstone the size of a hen’s egg and sometimes, if I was very good, a red chariot in which a photograph of him and Dori (short for Dorothy) had been mounted — him with a sheath of swords and arrows strapped to his back.

And I could spend hours looking at plans that became paintings that became sculptures that inspired children’s drawings that were embroidered on to cushion covers. His home was a fascinating, sometimes unsettling space, for a child to grow up in.

Pancho was not a distant intellectual. He loved his family. He was fascinated by each of our stories – and sometimes equally by his own flights of fancy that sprung from these. He would sit with my daughter at a table as he drew figures on request – birds, men on horses – with increasingly trembling hands.

He walked me down the aisle at my wedding, fulfilling his role as the only father figure I have ever known. But he knew that, on that day, the absence of my grandmother would be keenly felt, so he also cast himself in the part she would have played had she been with us: the creator of the cake. It must be remembered that this was a man who could not be trusted to boil an egg, and he certainly didn’t interfere with the baking or the icing, but rather drew a clear set of plans, detailing how each tier should look, to be delivered to the somewhat bewildered local confectioner.

He was a great father and grandfather, but his greatest love was always my grandmother. They were always together, arms linked, his hand covering hers. She was his greatest critic, and I can remember him once saying “It was such a good drawing, even Dori liked it!” as if this was the highest praise he could hope to achieve.

He was finally assured of her good regard when he was awarded one of many honorary doctorates. At the symposium that followed, she took to the podium to grant him another award: “And now,” she said, “to celebrate this eventful, stimulating and deeply fulfilling life that Pancho has lovingly shared with me, I wish to bestow yet another doctorate on him – a Doctorate Honoris Causa in Matrimony.”

He has requested that his ashes be mixed with hers. In his final years, he spent time with my mother in Johannesburg, and lived mostly on the farm in the Karoo with Kitty. He created sculptural angels and threatened to paint the shadows on the mountains – I’m not sure he ever got around to it. Instead, he enjoyed a quiet time, a winding down, though still with activity all around him, and with a book – and sometimes a cat – on his lap.

Yet when students or film crews visited him, he was filled with characteristic enthusiasm and insights for their projects and questions. It may seem to some that he faded away towards the end, but I like to think of these as his contemplative years. To borrow from his own poetry: “When is an architect most real?”

The Guedes clan will miss our patriarch terribly. But there is consolation in the fact that he lived his life well, completed it surrounded with love, and leaves behind a tangible legacy of buildings and objects and ideas – and people – for us to remember him by.

Pancho Guedes, alternative modernist

Guedes was born in Portugal in 1925, studied architecture at the University of the Witwatersrand (Wits), and worked in Mozambique until 1975. That year, he left Mozambique to take up the seat of professor and Head of the Department of Architecture at Wits. He then returned to Portugal, where he lived in Lisbon and a small village outside of Sintra, lecturing at three universities, and painted, sculpted and practiced architecture. He was awarded Honorary Doctorate Degrees by the University of Pretoria, University of the Witwatersrand and the Universidade Tecinica de Lisboa.

Guedes, who died on November 7, is described as an “alternative modernist” and was known for drawing on traditional African styles and creativity in his work. In 1962, he attended the first Congress on African Culture in Salisbury (now Harare), where he met Sir Roland Penrose, Tristan Tsara and Alfred Barr, and established himself as a collector of and authority on African art. He was subsequently invited to join Team 10, and regularly and enthusiastically participated in their assemblies.

This paragraph taken from his manifesto describes his architectural outlook: “We must become technicians of the emotions, makers of smiles, tear jerkers, exaggerators, spokesmen of dreams, performers of miracles, messengers; and invent raw, bold, vigorous and intense buildings without taste, absurd and chaotic, to invent an architecture the size of life. Buildings shall yet belong to the people, architecture shall yet become real and alive, and beauty shall yet be warm and convulsive.”