A vast global data leak has shed new light on one of SA’s most notorious corporate scandals, and may reinvigorate the state’s faltering attempts to prosecute the alleged mastermind.

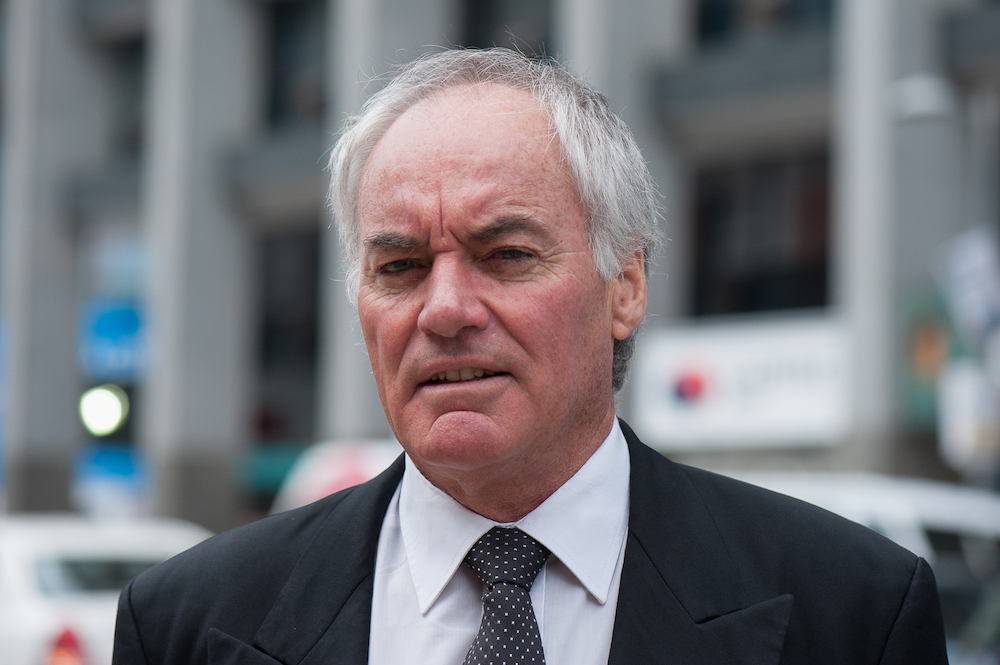

The leak provides a 15-year snapshot of KwaZulu-Natal farmer-accountant Gary Porritt’s business affairs in secretive offshore locations such as Panama, the British Virgin Islands and the obscure Pacific island of Niue.

Porritt’s arrest in 2002 led to the collapse of an investment fund underwritten by his high-flying Johannesburg-listed company Tigon.

About 2 950 investors in the PSC Guaranteed Growth fund — including a rural Free State school for intellectually handicapped children and, bizarrely, one of Porritt’s sons — lost a combined R162-million.

Under Porritt’s management, Tigon had blazed a trail across the JSE and was the best-performing stock for five consecutive years. Investigators later concluded that Porritt’s success was built on a series of frauds designed to manipulate Tigon’s share price and mislead the JSE and investors.

In 2005 the National Prosecuting Authority (NPA) charged Porritt and his associate Sue Bennett with more than 3 000 counts including fraud, stock exchange manipulation, contravening foreign exchange controls and racketeering.

Some of Porritt’s former colleagues pleaded guilty to related charges and spent time in jail. But Porritt and Bennett have fought a decade-long legal rearguard action, and have so far avoided facing the charges. They appeared in court again last month seeking a permanent stay of prosecution.The unprecedented leak of offshore company records was obtained by German newspaper Su?ddeutsche Zeitung and shared with the International Consortium of Investigative Journalists (ICIJ), whose partners include amaBhungane.

“collaboration with certain individuals aligned with the state”

The leak bolsters the state’s contention that Porritt masterminded an enormous financial racket. It shows that, between 1986 until his arrest in 2002, Porritt used the Panama-based law firm Mossack Fonseca to incorporate shell companies on his behalf in jurisdictions that offer a high degree of corporate anonymity. There is no evidence that Bennett had any dealings with Mossack Fonseca.

Porritt declined to respond to specific questions because they contained allegations pertaining to his pending criminal trial. He accused amaBhungane of “collaboration with certain individuals aligned with the state” attempting to influence court proceedings.

He also blamed his businesses’s collapse on unfair targeting by the South African Revenue Service (Sars), acting in concert with his competitors.

Sars could not respond to Porritt’s allegations by the requested deadline.

Mossack Fonseca helps clients shield their identities by providing nominee directors whose names appear on all official documents, as well as secretarial services for interactions with third parties.

While these services are not illegal, the gaps between what firms such as Mossack Fonseca know about their clients, and what they do for them, is wide open to abuse.

“My identity [must] never be revealed”

Porritt’s early foray into Mossack Fonseca’s offshore world is a classic example. In 1986 his businesses collapsed and his assets were sequestrated. According to the Mercury: “It was also around this time that the Gary Patrick Porritt Children’s Fund came into being. Porritt was reported to be a trustee at one point, and the trust owned 15 farms in the Kokstad area.”

The leaked offshore records show that Porritt acquired a Panamanian-incorporated company, Saints International, in December 1986. The following month Porritt sent an urgent message to Mossack Fonseca requesting that Saints International’s nominee directors offer to buy two KwaZulu-Natal farms and shares in a potato company owned by the Gary Porritt Children’s Trust.

“The properties are to be sold by public auction tomorrow. It is imperative that we make our bid prior to the auction or we will lose the deal,” Porrit wrote. “My identity [must] never be revealed.”

Although Porritt faces no charges with relation to this incident, it demonstrates his early grasp of the benefits of Mossack Fonseca’s services.

The firm did not respond to questions about Porritt, but told the ICIJ that “before we agree to work with a client in any way, we conduct a thorough due-diligence process”.

“We follow both the letter and spirit of the law,” it said. “Because we do, we have not once in nearly 40 years of operation been charged with criminal wrongdoing.”Over the next 15 years Porritt would open seven other shell companies via Mossack Fonseca and pay the firm tens of thousands of dollars in administration fees from a Swiss bank account. Swiss banking law is notoriously secretive. Until very recently, it prohibited banks from revealing account holders’ identities.

In this way, Porritt could wear a cloak of anonymity whenever he needed to operate beyond the oversight of business colleagues, investors and creditors, as well as regulators, tax- and law enforcement agencies. Crucially, it enabled him to do business with himself, but make it look to outsiders like a legitimate arms-length transaction.

No queries, no payments

Porritt allegedly engaged in multiple frauds in this way, bolstering his companies’ balance sheets by swapping assets and liabilities between companies, creating or erasing vast sums of money at a single stroke.

Most of the companies Porritt opened with Mossack Fonseca were instrumental to his alleged crimes. But it appears from the charge sheet that, although prosecutors knew about the existence of most of these companies and suspected Porritt’s hidden hand behind certain transactions, they did not realise the extent of his secret offshore control over them.

The NPA did not respond to questions.

In 1989 Mossack Fonseca provided Porritt with a marketing and loan agreement between a Porritt company, Effective Barter (Natal) and Fleur de Lys of Bordeaux. The agreement appears to have been for Fleur de Lys to market Effective Barter’s wines overseas.

Porritt submitted a tax refund claim of nearly R200-million for this marketing expenditure that led to a 20-year tax dispute between him and Sars.

Prosecutors now believe the agreement was a sham: “This loan account due by Effective Barter was running into millions of rands [but] it never received any queries with respect to this loan, nor were any payments ever made to Fleur de Lys of Bordeaux with regard to the repayment.”

Mossack Fonseca’s records confirm their suspicions: Porritt secretly controlled both parties to the loan agreement.

The charge sheet further alleges that between 1988 and 2001, Effective Barter falsely claimed R303-million in cumulative tax losses that included the agreement with Fleur de Lys. It claims that Porritt tried to offset the taxes owed by his other companies — including companies that drove Tigon’s share price — against Effective Barter’s huge false claim.

“a fac?ade and [an] artificial scheme”

In 1995, Porritt listed Tigon on the JSE. The following year, Tigon announced that it had raised nearly R50-million from issuing shares. A company called Gold Star bought 1.5-million Tigon shares.

The state alleges that Gold Star never paid for its shares and the leaked records show Porritt controlled Gold Star, having registered it on the Pacific island of Niue.

Tigon subsidiaries supposedly provided Gold Star with investment advice and claimed to have earned performance fees for Tigon in return. But the state alleges that Gold Star and others never paid any money to Tigon, and that it was “a fac?ade and [an] artificial scheme, with the intended effect that the Tigon group would report profits based on the performance of its own share price which … would in turn further increase the market price of the shares thereby artificially creating further profits”.

This alleged scam is central to the charges Porritt faces of overstating Tigon’s earnings by R26-million over two financial years.

Porritt later opened two more shell companies via Mossack Fonseca, which he used to conduct ever more audacious transactions. He allegedly claimed fictitious profits for Tigon by selling hugely overvalued and largely intangible intellectual property and trademarks to another JSE-listed company he controlled, Shawcell Telecommunications.

Shawcell in turn claimed tax allowances against the same assets. At various times, nominal ownership of the intellectual property and trademarks passed through Porritt’s Mossack Fonseca-incorporated companies.

“a large asset base outside SA”

By 2000, Tigon’s headline earnings per share was galloping along at an annual average return of 145%. The PSC Guaranteed Growth Fund — which prosecutors claim was de facto managed by Porritt — persuaded 2 950 investors to invest R162-million in Tigon and Shawcell shares.

Among the drawcards for investors, says the charge sheet, was that Tigon claimed to have “a large asset base outside SA through operations conducted through its foreign subsidiaries”. But at least one of these subsidiaries was a Mossack Fonseca- administered shell company.

When the fund collapsed in 2003, liquidators tried to trace the money back through Porritt’s web of companies and failed. Mossack Fonseca’s staff only realised something was amiss when their bills for Porritt were being returned undelivered. They finally looked him up online and learned of his arrest almost 18 months before.

“The name of our company is not mentioned in any of the [news] items,” wrote a relieved staffer, “but taking into account the bad reputation that this could bring, I suggest [we] resign as directors and registered agent of all [his] companies.”

The amaBhungane Centre for Investigative Journalism produced this story. Like it? Be an amaB supporter and help us do more. Know more? Send us a tip-off.