The crowd at the Union Buildings on August 9 1956. About 20 000 women marched to Pretoria to protest against passes for black women.

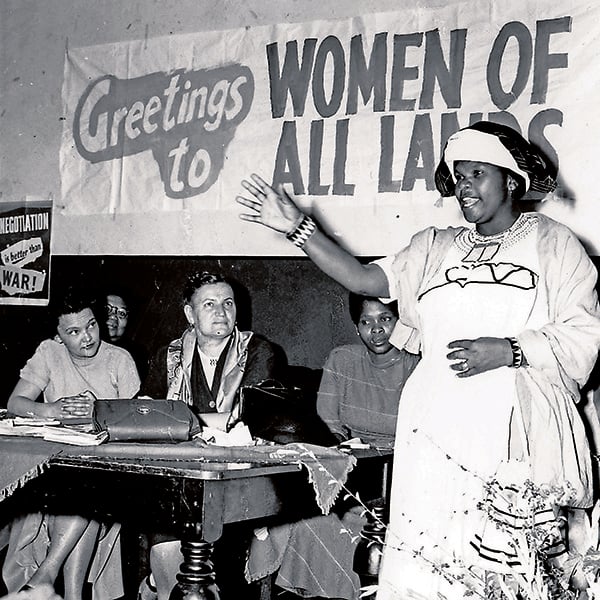

11. Dora Tamana

Dora Tamana was born in Hlobo, Transkei in 1901. Her father and two of her uncles were among those killed at the Bulhoek Massacre in 1921. In 1923, she married John Tamana, and the couple relocated to District Six in Cape Town. Tamana’s husband often squandered the family’s meagre income on cars, alcohol and girlfriends, and in 1948, he left her and their children.

Tamana’s involvement in politics began when the government decided to clear and re-house squatters in Blouvlei, the informal settlement where she lived, and the Communist Party of South Africa (CPSA) became the first of many organisations she joined. She later became a member of the ANC, and was heavily involved in mobilising women against the imposition of passes.

Tamana was elected the national secretary of Fedsaw in 1954. Soon thereafter, she and Lilian Ngoyi attended a World Congress of Mothers in Switzerland, and visited China and Russia. This drew the attention of the government and upon her return to South Africa in April 1955 she was banned from a number of organisations and from attending political meetings for five years.

In the following years she suffered constant police harassment. During the 1960s, she was imprisoned twice, and her health deteriorated to the extent that she could no longer work. However, she continued to participate in local affairs for many years, joining a group of women to protest high rents, and to start projects such as first-aid classes and crèches in townships.

In 1981, the United Women’s Organisation was officially launched with 400 delegates from the Western Cape. The 80-year-old Tamana opened proceedings from her wheelchair, urging women to unite. She died in July 1983. — Fatima Asmal

12. Dorothy Nyembe

Dorothy Nomzansi Nyembe was born in 1931 at Talane, near Dundee in northern KwaZulu-Natal. She attended local mission schools until standard nine, when she gave birth to her only child at the age of 15.

Nyembe earned a living as a hawker, and joined the ANC in 1952. In 1954 she participated in the establishment of the ANC Women’s League in Cato Manor and was named chairperson of the “Two Sticks” branch committee. She then became vice-president of the Durban ANC Women’s League and a leading member of the Federation of South African Women.

Nyembe was one of the leaders against the removals from Cato Manor in 1956, and also led boycotts of the government controlled beer hall, which was seen as a threat to traditional beer brewing — an important source of income for township women. An obituary by Paul Trewhela in January 1999 said that during her funeral at Umlazi “one respectful man ruefully reflected that he still carried the scar where Nyembe had hit him during the beer hall protests”.

She led the Natal contingent of women to the Women’s March on the Union Buildings in Pretoria and was among the 156 arrested and charged with high treason. However, the charges against her and 60 others were later dropped. In 1959 she was elected president of the ANC Women’s League in Natal, and in 1961 she was recruited into Umkhonto we Sizwe. In 1962, she became president of the Natal Rural Areas Committee, and participated in the Natal Women’s Revolt.

In 1963, Nyembe was arrested and charged with furthering the aims of the banned ANC. After her release from prison in 1966, she was served with a five-year banning order. In 1968 she was detained with 10 others and charged under the Suppression of Communism Act. In 1969 she was found guilty of harbouring members of Umkhonto we Sizwe and was sentenced to 15 years’ imprisonment. After her release in 1984, she became active in the Natal Organisation of Women.

In 1994, she became a Member of Parliament. She was honoured with the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics People’s Friendship Award and the Chief Albert Luthuli prize for her commitment to the liberation struggle. Nyembe died in 1998. — Tracy Burrows

13. Elizabeth Mafeking

Elizabeth “Rocky” Mafikeng was born in 1918 in Tarkastad, a small town in the Eastern Cape. Her father died shortly after she was born, forcing her mother to work as a cook in a hotel. To assist the family, Mafikeng began selling fat-cakes to factories near her home at the age of 14 and worked at a canning factory, where she cleaned basins of fruit for 75c a week.

Her political life started in 1941, when she joined the Food and Canning Workers’ union. Between 1954 and 1959 she served as president of the African Food and Canning Workers’ Union (AFCWU) and branch secretary in Paarl. She also joined the Paarl branch of the ANC and in 1957 became the vice-president of the ANC Women’s League.

Mafikeng was one of the founder members of the Federation of South African Women (Fedsaw). She was served with a banning order in 1959, shortly after she led a huge demonstration in Paarl against an attempt to issue passes to African women there. She fled to Lesotho with her one-month-old baby, and lived in a remote area there. Both her mother and her husband died while she was in exile, but she was unable to attend their funerals.

She returned to the Cape in 1991 and lived in Mbekweni township in Paarl, in a house built for her by the Food and Allied Workers Union. — Fatima Asmal

14. Ethel Leisa

“Ma” Ethel Leisa was born in Ga-Marishane in Limpopo, in 1914, two years after the ANC’s formation. Upon completion of her schooling, she moved to Johannesburg to train as a nurse. It was in the big city that she experienced racial and gender discrimination firsthand, and it shocked her.

“This was when I decided to take part in the fight against apartheid,” she said.

Choosing to take an under-the-radar stance, Ethel was careful to participate only in local township meetings rather than larger public gatherings, thereby ensuring her efforts were discreet but still helped the cause.

Working as a nurse at Shanty Clinic in Orlando West, Ethel joined the Federation of African Women closely assisting “Ma” Lilian Ngoyi, the first woman elected to the executive committee of the ANC and co-founder of the federation.

A member of the ANC Women’s League, she ran a safe house for ANC comrades on the run, and became renowned as a teacher, mentor and “mother” for activists.

With her underground position, she played an active role in supporting the ANC leaders on trial for treason and sabotage during the 1950s and 1960s, helping to raise money for their families and arrange for schooling, clothing and emotional support. — Linda Doke

15. Fatima Meer

(Photo: Robben Island Mayibuye Archives)

Professor Fatima Meer was born in 1929 in Durban, and raised as one of nine children. Her father Moosa Ismail Meer was the owner and editor of the influential Indian Views newspaper. Meer studied at the University of Natal and Wits University, completing her master’s in sociology.

Meer started the Student Passive Resistance Committee, joining the 1946 Passive Resistance Campaign and addressing mass meetings of South African Indians. In response to the violent Durban race riots in 1949, she was part of establishing the Durban and District Women’s League, working together with the ANC Women’s League to build alliances between black and Indian communities.

She married in 1950, and she and her husband Ismail “IC” Meer worked to build relationships and networks between the segregated races of South Africa.

Meer participated in the Natal activities of the 1952 Defiance Campaign, and was arrested and banned by the apartheid government from 1952 to 1954. However, she continued to speak out, eventually becoming one of the most recognised voices of the Black Consciousness Movement.

Due to her prominence and organising success, she was one of the first women leaders approached in Natal when the idea of the Federation of South African Women (Fedsaw) was birthed. Her spearheading of the Women’s March was critical in ensuring women from Natal formed part of the protest on August 9 1956.

Meer lectured sociology at the University of Natal in 1959, becoming the highest-level black academic at a white university in South Africa. She travelled abroad several times, but the apartheid government refused to renew her passport after the June 1976 Soweto Uprising. She was banned for another five years, restricting her movement, association, writing or publishing. Fortunately, she could continue to teach.

Fedsaw was effectively silenced by the apartheid regime when it was forced to go underground, and many of its members were banned or imprisoned in the 1960s. Meer, together with Winnie Madikizela-Mandela, attempted to revive Fedsaw in the 1970s. She was elected the first president of the South African Black Women’s Federation in 1975.

In the 1980s and into the 1990s, she worked with NGOs fighting for the rights of shack dwellers and urban migrants. She was also involved in building schools, a teaching college and a crafts centre, as the leader of the Natal Education Trust. When Meer was arrested for breaching her banning order, the apartheid government shut these projects down.

Meer continued to work with NGOs after 1994, as well as advising the government. She worked to cancel third world debt as a member of Jubilee 2000. Nelson Mandela entrusted to Meer the task of his first authorised biography, Higher than Hope, in 1990.

A prolific writer as well as an academic, she authored several books, numerous articles and a film screenplay. She died in Durban in 2010 at the age of 81. — Romi Reinecke

16. Fatima Seedat

Fatima Seedat was born in 1922 in the Strand, near Cape Town, where she attended Trafalgar High School until age 15.

Seedat’s political awareness was sparked as a teenager as she became aware of the impact of the segregation laws. She joined the Communist Party, and moved to Durban when she was 23 to marry Dawood Seedat, a fellow Communist Party member. There she became actively involved with the politics of the Indian community and joined the Natal Indian Congress.

When the organisation joined forces with the ANC as a result of the Dadoo-Naicker-Xuma Pact (also known as the Joint Declaration of Cooperation or “Three Doctors Pact”) in 1947, Seedat also became a member of the ANC.

When her first child was just four months old, Seedat was arrested for her role in passive resistance in the Durban area. She was jailed a second time in 1952 for her role in the defiance campaign, and was sentenced to one month of hard labour.

In 1956 she took part in the historic Women’s March to the Union Buildings. Two days later Seedat presented at the Second National Conference of the Federation of South African Women, where she spoke of the importance of opposing the Group Areas Act, and the powerful role women could play in helping to free South Africa from apartheid.

“Women from all over the world are playing an increasingly important role in the life of their countries. We women in South Africa too have the duty to play a great role in our beloved country. Let us women stand together and build a mighty Federation of South African Women, so that we can all march forward to free South Africa from racial prejudice,” she said.

Eight years later, Seedat and her husband were banned for five years under the Suppression of Communism Act. Although she remained a member of the ANC after this, her health deteriorated due to diabetes and she died in 2003.

17. Florence Matomela

(Photo: Robben Island Mayibuye Archives)

Born in 1910, Florence Matomela worked as a teacher while raising her five children. She died at just 59, but hers was a life rich in sacrifice for her fellow countrymen and women.

In 1950, she led a demonstration against new influx control regulations in Port Elizabeth. She was one of the first women to volunteer for the 1952 Defiance Campaign and she spent six weeks in prison for civil disobedience.

During the mid-1950’s Matomela was the Cape provincial organiser of the African National Congress Women’s League (ANCWL), and the vice-president of the Federation of South African Women, which was one of the organisers of the 1956 Women’s March to the Union Buildings in Pretoria against the pass laws.

Matomela was among the original 156 defendants in the Treason Trial, but charges against her were later withdrawn. In 1962 she was banned, and restricted to Port Elizabeth. She was also given a five year-sentence for furthering the aims of the banned ANC, and her health deteriorated severely while she was in prison. She was at times deprived of the medical attention she needed, including insulin to treat her diabetes. After her release she was banned again, and remained so until her death in 1969. — Fatima Asmal

18. Florence Mkhize

(Photo: Robben Island Mayibuye Archives)

Florence Grace Mkhize, known affectionately as Mam Flo, was a daring, determined and resourceful anti-apartheid activist and a leader in the women’s movement.

Mkhize was born in 1932 in Umzumbe, on the Natal South Coast, sharing in the privations of South African black women. From her teenage years she was determined to be part of the solution, and joined the ANC. By the age of 20, Mkhize was at the forefront of the struggle.

She joined the 1952 Defiance Campaign and was banned by the apartheid government soon after. However, she continued to communicate and organise with her comrades. Mkhize secretly used her place of work, a sewing factory in Durban, as their base.

Her obvious political maturity saw her assigned to ensuring participation in the forming of the Freedom Charter. After all her hard work, the bus on which Mkhize was travelling to Kliptown for the Congress of the People was stopped by the police and turned back to Natal, along with many other buses also on their way to the event.

Despite living under a banning order throughout the 1950s, she a key organiser within the Federation of South African Women (Fedsaw) in Natal. Her support gave the new organisation credibility, legitimacy and strategic direction in the province.

She mobilised many women to travel and attend the planned Women’s March on August 9 1956. Again, however, Mkhize and her bus full of delegates travelling to Pretoria was stopped by police and forced to return to Natal.

As a member of the South African Communist Party, she was one of the leaders of the potato and tobacco boycotts against apartheid-colluding industries in 1959. After the ANC was banned in 1960, she continued the fight underground and arranged legal representation for many young people arrested for political activities. She participated in the South African Congress of Trade Unions until its structures were also destroyed by the government. In 1968, she was banned again under the Suppression of Communism Act.

Undeterred, she redirected her organising skills into the Release Mandela campaign in the 1970s. Her family’s home was a hive of activity, often sheltering comrades in hiding from security forces. A community activist at heart, she was tireless in tackling the education and housing crisis in Lamontville, south of Durban, during the 1980s. She flew to Amsterdam to successfully raise funds for the children of political activists who were refused admission to state schools.

She was also a founding member of the non-aligned United Democratic Front in 1983, as well as organising women across racial lines in the affiliated Natal Organisation of Women.

After South Africa’s first democratic election, and despite her failing health, Mkhize’s community work in Lamontville was unceasing, and she was elected ward councillor in 1996.

The ANCWL awarded Mkhize the Bravery Award in 1998, and Nelson Mandela bestowed a South African Military Gold Medal on her in Durban in 1999, shortly before she passed away. An HIV facility she had fought to create in Lamontville was completed the following year.

19. Florence Mophosho

Florence Mophosho was born in 1921 in Alexandra Township in Johannesburg. Household conditions forced her to drop out of school in standard six, and work first as a domestic worker, then in a factory. Inspired by the 1952 Defiance Campaign, she joined the ANC. She was instrumental in organising the Congress of the People, which adopted the Freedom Charter in 1955, and was actively involved in the women’s movement. She became a full time organiser for the ANC and participated in many of the campaigns of that time. Mophosho mobilised women in Alexander – her birthplace – for the Transvaal demonstrations against the passes for African women, and also participated and mobilised women to participate in the nationwide anti pass women’s march on 9 August 1956. She mobilised domestic workers in the urban areas and later in the rural areas, including Lichtenburg. In 1960 when the government announced the state of emergency Florence went underground and continued to further ANC objectives. She was detained on numerous occasions and banned in 1964, after which she went into exile to Lusaka and later to Tanzania. Mophosho was elected to the national executive council of the ANC in 1975, and re-elected in 1985. She died less than two months later in Lusaka on Women’s Day, August 9 1985. – Fatima Asmal

20. Frances Baard

(Photo: Robben Island Mayibuye Archives)

Frances Goitsemang Maswabi Baard was born in 1901 in Beaconsfield, Kimberley, in the Northern Cape. She trained as a teacher, and then moved to Port Elizabeth, where she worked as a domestic worker, and then in the food and canning industry.

A natural organiser, she became a leading member and rose to secretary of the Food and Canning Workers Union, and was influenced by Raymond Mhlaba. She would later be on the executive committee of the South African Congress of Trade Unions.

She joined the ANC in 1948 and fast became leader in the ANC structures of the Eastern Province, as well as the ANC Women’s League (ANCWL). In the 1952 Defiance Campaign, she was an ANCWL organiser in the Eastern Province.

In April 1953 Baard held a meeting with Ray Alexander Simons and Florence Matomela that galvanised the creation of the Federation of South African Women. Baard founded the Port Elizabeth branch of Fedsaw, and was on its executive committee.

Due to her active involvement in the Freedom Charter, Baard was arrested in the 1956 Treason Trial. She was detained again in 1960 and 1963, imprisoned at age 62 in solitary confinement for 12 months. Afterwards she said: “I nearly went off my mind”.

In 1964 she was finally sentenced for contravening the Suppression of Communism Act, with a punishment of five years imprisonment for her involvement in ANC activities. When she was released from prison in 1969, she was banned under apartheid state laws, restricting her movement, association and personal freedoms. Far worse than this was the cruelty of the apartheid state in forcing her apart from her children and family. Baard was banished from the Eastern Province into exile, in what was then the Transvaal.

She was unable to leave Mabopane township, near Pretoria, so that her punishment included isolating this mother and leader of many, to a strange place where she had no relatives and knew no one. When she was banished, the municipality also evicted her children from their family home, forcing them to scatter across the country.

Nevertheless she persevered in activism, becoming a patron of the United Democratic Front in the 1980s. She wrote a moving account of her experiences with Barbie Schreiner, entitled “My Spirit is Not Banned”.

Baard passed away in 1997. The seat of Frances Baard Municipality in the Northern Cape is Kimberley — her birthplace.

When Hilda Bernstein interviewed Baard in the 1970s, she noted Baard’s indestructible spirit. Her final words on her experiences were: “I have survived”. — Romi Reinecke

1-10

21-30

31-40

41-50

51-60