Finance Minister Pravin Gordhan delivers his 2016 budget speech.

Apart from a few welcome glimmers of relief, the 2017 budget did not offer the average citizen much joy.

But for wealthy individuals, the budget may well have put a few noses out of joint.

Thanks to dismal economic growth and a consequent decline in taxes collected, Finance Minister Pravin Gordhan had very few levers to pull to increase the government’s revenues.

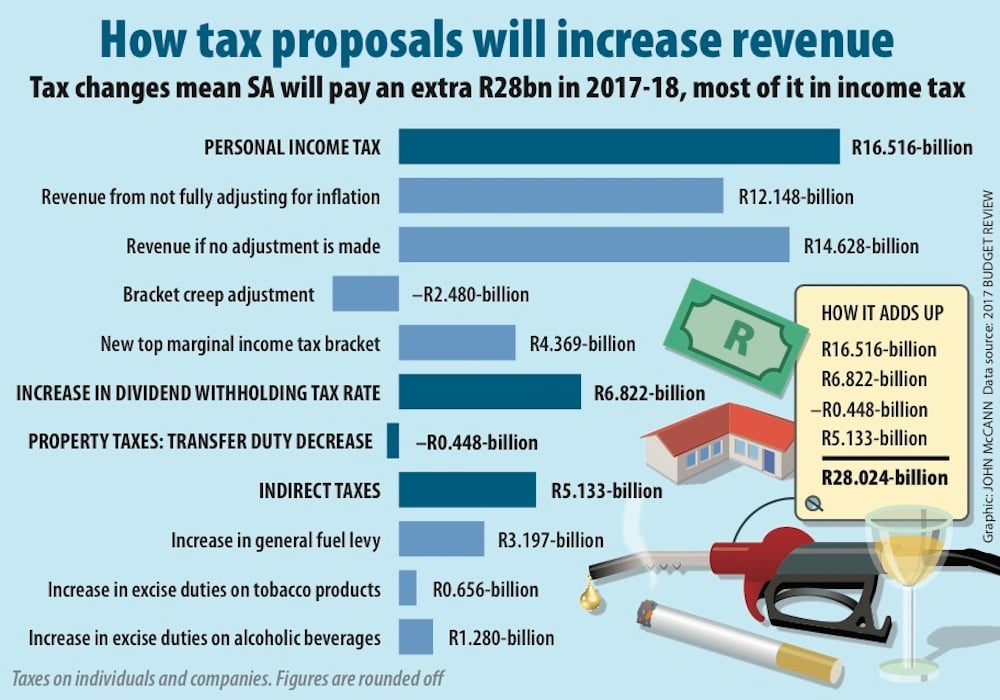

Despite some expectations that he would increase value-added tax (VAT), Gordhan avoided what is widely deemed a regressive and politically unpalatable step by introducing other measures to raise an additional R28-billion for the coming 2017-2018 year, mainly through personal income tax.

A VAT increase has not been ruled out entirely, with another R15-billion being sought for the 2018-2019 year, although the proposals to raise this will come only in the 2018 budget.

Taxpayers across the board will feel the pressure from a limited adjustment for inflation or bracket creep, and an increase in excise taxes, but the wealthy will be hit harder than the rest.

New measures include an additional tax bracket, with a marginal tax rate of 45%, for people with taxable incomes of more than R1.5?million and an increase in the dividends withholding tax from 15% to 20%.

A dividends withholding tax is subtracted and withheld by a company or intermediary before a net dividend is paid to the shareholder.

Revenue from the new tax bracket is expected to yield R4.4-billion and the increase in dividends withhoding tax is expected to bring in an additional R6.8-billion.

The additional tax bracket will affect about 100 000 people. According to the treasury’s figures, the increased rate will raise the amount a person with taxable income of R2-million pays in the coming year by slightly more than R19 000.

But a large amount of the additional money will come from the limited relief the treasury has given to personal income taxpayers to adjust for bracket creep.

Bracket creep occurs when personal income taxes are not fully adjusted for inflation, so that inflationary salary adjustments increase the effective tax rate individuals pay and reduce real income.

The effect of only providing partial relief is expected to raise about R12.1-billion.

Along with the subdued relief about bracket creep, “sin taxes” will be going up. Increases for alcohol and tobacco will raise slightly less than R2-billion, with increases in the fuel levy expected to net just over R3-billion.

A hotly debated tax on sugary drinks is expected to be added to this suite of tax measures later this year.

Gordhan did a good job of balancing the books, given the constraints he is operating under, said Malusi Ndlovu, the head of Old Mutual Corporate Consultants, although the budget was not entirely “a good story for consumers”.

Nevertheless, there was some relief for people from lower- to middle-income households, aimed at stimulating investment and efforts to grow savings.

The government proposes raising the duty-free threshold on the purchase of residential property from R750 000 to R900 000 from March 1. This could help to encourage people to buy homes or invest in residential property, and provide welcome relief for first-time buyers.

Harry Nicolaides, the chief executive of Century 21, welcomed the move, particularly because first-time home buyers make up the bulk of the property sales market.

It could stimulate property sales in this bracket, he said, because it may serve as a “catalyst for consumers who wish to sell their property below R900 000 and who then go on to buy more expensive properties”.

The budget did offer other ways for individuals to mitigate the impact of tax changes, said Ndlovu, notably through tax-preferred vehicles such as tax-free savings accounts. The government has increased the annual allowance for tax-free savings accounts to R33 000, adjusting for inflation.

The steps laid out by Gordhan were not regressive and will protect lower-income earners, said Tarryn Atkinson, the chairperson of the South African Institute of Chartered Accountants’ employee tax and expatriate subcommittees.

Given increased expenditure on items such as education and social welfare, Gordhan “ticked the right boxes”, she said.

But the biggest complaint was that revenue continued to be drawn from a relatively narrow tax base at the upper tier of income earners, said Atkinson. “Higher income [earners] are going to feel this budget.”

Including the 100 000 or so individuals in the new tax bracket, personal income tax is to be paid by a relatively small base of 7.4-million taxpayers, according to treasury data.

The increases on the dividends withholding tax came “as a surprise”, said Atkinson, although the explanation given made sense.

The combined move to increase the top marginal rate and the dividends withholding tax decreases the opportunity for individuals to pay themselves with dividends rather than salaries, according to the treasury.

The exemption and rates for inbound foreign dividends will also be adjusted in line with the new rate, according to the treasury.

Gordhan was limited in terms of how much more he could take from personal income taxpayers, Atkinson said.

“There need to be other measures in place because we cannot keep mining the same tax base all the time,” she said.

If, alongside the increased revenue measures the government put in place, it managed to deliver on the targeted costs savings and efficiencies, South Africa may be in a better position down the line, she added.

The treasury appears aware of this pressure. In its budget review, it did warn that “continuing to raise the personal income tax burden over a long period could have negative consequences for growth and investment”.

If economic growth does not accelerate in the coming three years, it may be necessary to make changes to consumption taxes.

“The least economically damaging means of doing so would be to increase the VAT rate, which is low by global standards,” the review said. This would be balanced against the effect it would have on poor households, although these could be mitigated by targeted public expenditure.

Ndlovu said Gordhan made the right call on VAT. Aside from the question of it being regressive and disproportionately affecting low-income earners, to address the revenue shortfalls a steep increase in the VAT rate would have been needed.

“That, psychologically, is very difficult to do,” he said.

But what he found concerning was the “unhinging” of the tax bracket structures that personal income tax is built around. The addition of the new tax bracket comes on the heels of last year’s increases to the top marginal rate of 41%.

“It’s not just a change in the levels [of tax]; it’s a change in the structure,” said Ndlovu.

If growth prospects did not improve, then more changes like this will be likely in the future.

This increased complexity for taxpayers had created more uncertainty both for individuals and the markets in general, he said.