This photo of people from Britain’s colonies in Africa is one of the 40 propaganda photos taken by Albert Grohs in the Ruhluben internment camp near Berlin. It is part of the Maurice Ettinghausen Collection of papers at the Harvard Law School Library

‘If you try to gramophone me, I’ll kill you!” Toby Roberts yells furiously. The internee from West Africa is a character in Wallace Ellison’s autobiographic novel Escaped! Adventures in German Captivity of 1918. The scene is meant to illustrate the ignorance of the imprisoned seamen from West Africa, who, in Ellison’s racist literature, are illiterate, simple-minded and “little more than savages”.

The author illustrates that Roberts cannot differentiate between “gramophone” and “chloroform”. Surely, Ellison continues, the prisoner meant to say: “If you try to chloroform me, I’ll kill you.”

The name “Toby Roberts” appears in The Index of British Fishermen and Merchant Seamen taken Prisoner of War (POW) in 1914-18, held at the United Kingdom’s National Archives.

Ellison may have found it enlightening to know that hundreds of these African seamen were indeed “gramophoned”, as part of a study by German and Austrian scientists.

During World War I an estimated 750 000 Africans were sent to battle in Europe. The presence of non-Europeans was seized on in 1915 by a group of German linguists, anthropologists and scientists who formed the Königlich Preussische Phonographische Kommission (Royal Prussian Phonographic Commission).

The group produced more than 2 000 acoustic recordings of languages and music with POWs in German camps and the Odeon recording studio in Berlin between 1915 and 1918.

Of the 350 recordings in more than 30 African languages that have survived, few have been translated. Those that have offer an insight

into the often neglected and forgotten experiences of African soldiers and civilians in these foreign lands.

They had not fought in the Great War, but were caught in the maelstrom of belligerent politics. Some men were deported straight from their ships, like the seaman from the Eastern Cape, whose name was probably Josef Ntwanambi. Khwel’itrain! (Get on the Train!) he sings on one of his recordings.

Others had lived in Germany for years, such as the seaman from Liberia, who appears in the Red Cross registration of POWs with the Germanised name of Stephan Bischoff and whose address was Auguststraße 4 in Berlin. Bischoff was recorded by the commission and would later become a language assistant at the Hamburger Institut für Kolonialsprachen, under the aegis of Carl Meinhof.

Ntwanambi did not come to Europe as a “war worker”, like many of his compatriots in the South African Native Labour Contingent.

The black South Africans who travelled to European battlefields were called “war workers”, because the British Army would not, like the French Army, consider arming Africans.

This offence has left an imprint in popular culture: “It is very hard and difficult to face the Germans without arms!” went the song of Nimrod Makanya, later popularised by the Bantu Glee Singers.

When Ntwanambi sang into the gramophone’s microphone, he had other things on his mind. He did not fight in the war, but was interned after his ship arrived in Hamburg.

Unlike Roberts, Ntwanambi was not fictionalised in a novel. Yet he was racialised as an object of colonial linguistics.

In a note addressed to his colleague Felix von Luschan, Carl Meinhof, one of the founders of Afrikanistik (African studies) in Germany, described Ntwanambi as “racially interesting” and asked the anthropologist if he could examine him. Luschan, like Meinhof, was a member of the commission.

His answer to Meinhof’s postcard cannot be found, because Meinhof’s house in Hamburg burned down during the air raids of World War II. Therefore, whether Ntwanambi was measured and examined remains unclear.

War also destroyed the registers of the German POW camps, so searching for the traces of the prisoners becomes a question of luck.

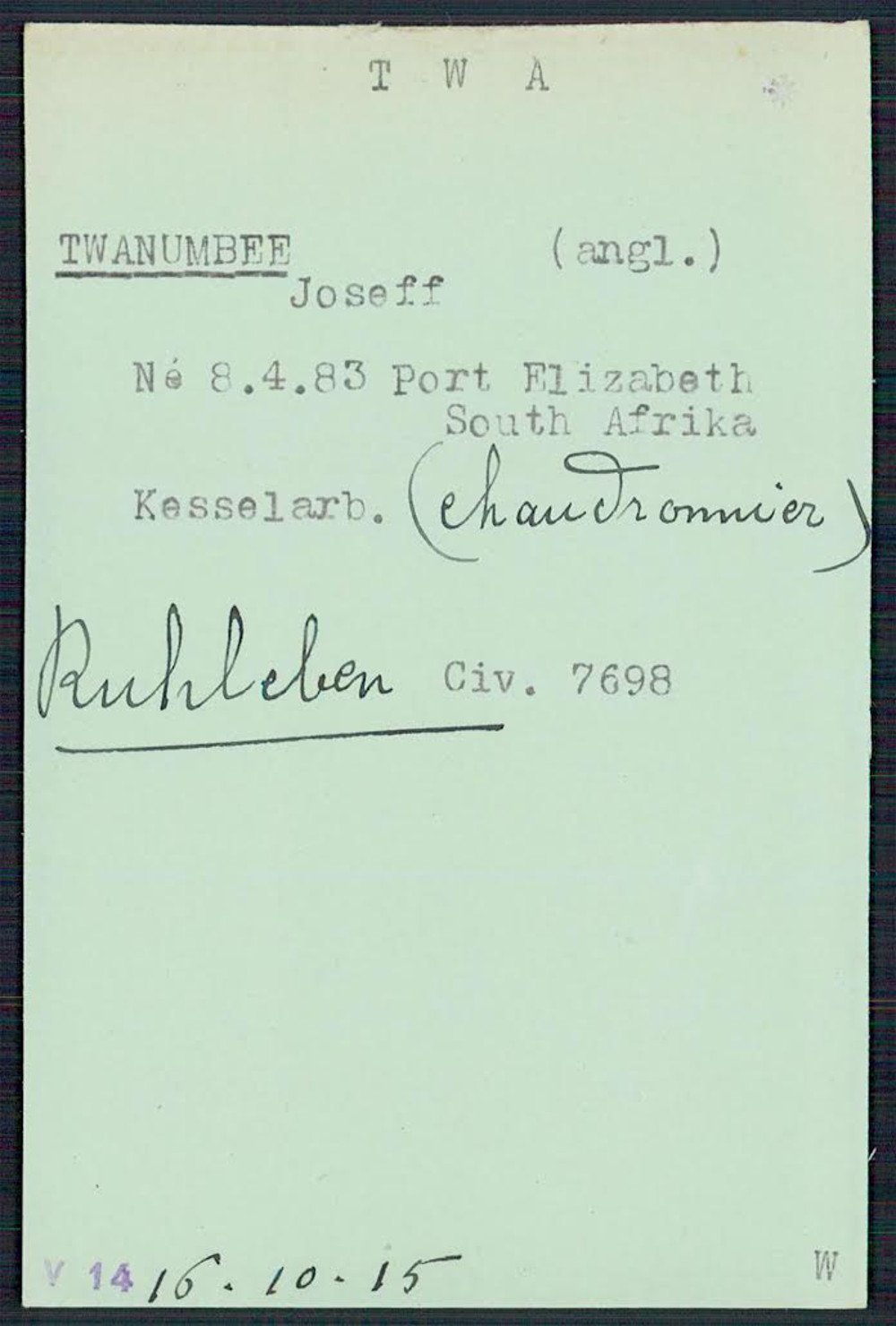

In the case of Ntwanambi, a snippet appears in the registers of the Red Cross that testifies to his presence. His name is variously registered as Twanumbee or Tuanambi. As with so many cases, the misspelling of non-European names complicates the identification of personal traces. According to the Red Cross register he was born in Port Elizabeth on April 8 1883 and was registered as a prisoner on October 16 1915.

In the written files of the commission, now held at the Lautarchiv (sound archives), Ntwanambi appears in an entry dated May 19 1917, when he was acoustically recorded by Meinhof and the philologist Wilhelm Doegen. According to the files of the Lautarchiv he had spent time in India after 1897. The protocol of his recording also states that he could read and write very little.

Only from the Red Cross files do we learn that he worked on a ship as a boilermaker.

During his recording, Ntwanambi did not sing of the war, having not seen the European battlefields. His chanting, melancholy voice instead sings of being incarcerated in a camp, an experience he artfully compares with the phase of seclusion in the rites of initiation.

In his songs, the inmates of the camp become abakhwetha (initiates).

In Phindezwa Mnyaka’s translation and with her interpretation of the songs that were captured by the commission, the profound beauty of these compositions and their inherent wealth of associative poetics emerge. His, like many other men’s recorded voices, articulates aspects of their experiences in captivity of uncertainty and fear.

Despite their age, the recordings sound astoundingly clear. The acoustic recordings in isiXhosa include series of words spoken by Ntwanambi. One of these series gives away Meinhof’s search for the names of God in African languages (Thixo, uThixo … inkosi, inkosin …). Another registers the pronunciation of clicks in isiXhosa: Umngqungqo, ncwadi … yincwadi … The songs that Ntwanambi sang were most probably recorded to get examples of “traditional” texts, and the flow of spoken language more generally.

Yet what was deemed a traditional song becomes interlaced with references to Ntwanambi’s situation of captivity, carrying a poignant sense of misery.

Ntwanambi’s chanting voice introduces the topic: “Initiates, there

I go hungry! We go hungry, Father!” he sings. His repeated reference to constant hunger, which would have been blacked out in the outgoing letters of prisoners by the censors, sharply contradicts the propaganda photograph of happy, well-fed men.

In contrast to the letters, the spoken, recorded words were not censored. They were not meant to leave the enclosure of the “museum of voices” and the field of linguistic research for which they were recorded.

In one of the few publications of the Lautarchiv, (from 1936), Ntwanambi’s chanting voice, which sets the stage for his words, is dismissed as “meaningless ejaculations”. Listened to today, not as an example of a language to be registered and researched, but as a historical document that speaks of the presence and the experiences of African internees, it’s a narrative of Ntwanambi’s journey to the camp.

Whether he was released or whether he returned to South Africa I could not find out.