“Technology has value but it doesn’t have values

For those on the outside looking to break in, jobs in journalism are scarce. And, for those on the inside, working in the chaos of constant change is yet another reason journalism is rated among the worst jobs in the world.

In South Africa, all major news publishers, including the Mail & Guardian, have gone through painful retrenchments. Leaner newsrooms are meant to serve the added technological imperatives of our journalism better.

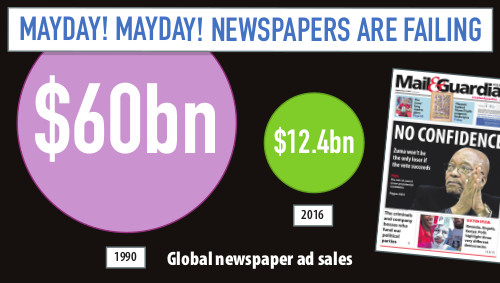

It’s also meant to serve profit margins better as print revenues continue to dwindle and digital revenues fail to keep pace with the deficit.

It’s not just South African newsrooms that are under pressure. Journalists searching for work in the United States have found that jobs they apply for one week may be scrapped the next as publishers opt for more video output.

Vocativ, an online news and analysis site, which uses deep web technology to develop stories, strategically shifted its entire newsroom on to video. But it is not alone. MTV News, which focuses on entertainment, recently restructured, moving away from long-form written content to short-form video, “more in line with young people’s media consumption habits”. Vice Media, which forges content partnerships and branded content aimed at younger people, also laid off 60 people to focus on video.

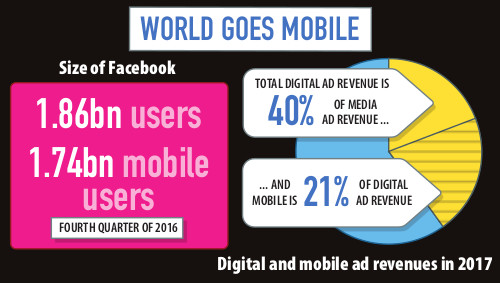

Facebook chief executive Mark Zuckerberg sees the future of all digital content, not just news, dominated by video.

“I just think that we’re going to be in a world a few years from now where the vast majority of the content that people consume online will be video,” Zuckerberg said at a conference in Barcelona last year.

As Richard Gingras, a senior director of news and social products at Google, says: “Technology has value but it doesn’t have values.”

Young people particularly are watching more video online, forcing news publishers to innovate with video formats. The shift to video stems from the reliance on Facebook and Google to direct traffic to the digital properties of news publishers.

According to a study by Antonis Kalogeropoulos and Nic Newman of the Reuters Institute at Oxford University, fewer than half the people who find a story from social media correctly remember which publication published it. But roughly two-thirds of those same people are able to remember correctly which social media channel led them to the story.

It’s more terrible news for the likes of the M&G. We can hardly maintain a loyal readership base if our audience can’t even remember our name.

And then there is a drive towards publishers disseminating content directly on to Facebook platforms and Google, inspiring fierce competition between the tech giants for a larger share of the market.

Although Facebook is the world’s largest social media platform, it still falls short on video. YouTube continues to dominate that category, with more than one billion hours of video watched every day — about 10 times what Facebook generates.

Facebook, however, has strategically calculated its news feed algorithm to prioritise native video content in the news feed — video that is uploaded directly on to the platform.

And, although there is a definite upsurge in video views, the shift to video is also a workaround the waning efficacy of digital display advertising.

But this has come at great cost to news publishers. Google and Facebook are now the greatest recipients of digital advertising revenues, creating a duopoly that threatens the future viability of digital news publishing, which relies on advertising alone.

Gingras says Google cannot bear the responsibility for the shifts in news production and consumption alone.

“There are lots of challenges in the ecosystem today,” he says, pointing out that Apple, as a hardware giant, also has a role to play in the emerging ecosystem of digitally distributed news.

The ecosystem Gingras refers to includes publishers, citizens, governments and tech giants, who all must somehow come to an understanding about how best to ensure that technology does not fritter away the worth of journalism in a free society.

“How do we collectively evolve our approaches to try to make sure that we’re doing right by the societies we live in?” he asks.

Key to the future of news media is whether trust in publishers can be restored. The 2017 Edelman Trust Barometer, released in February, found that trust in the media in South Africa dropped to 39% in 2017 from 45% in 2016. This compares with a 43% global average.

“Legitimate news organisations are indeed competing with the blogger,” Gingras says. “They are also competing with some site that’s actually a corporate advocacy site, or a state-sponsored site, and it’s hard to know the difference.”

He acknowledges that Google is an expected to do more to distinguish news produced by journalists, an issue Google is addressing somewhat by collaborating on projects to ensure journalism stands out in the chaos of the web. But the problem is as much an issue for news publishers as it is the nature of the web.

“The web, over the last 20 years, has got ponderously slow and the advertising behaviours have become outrageously disrespectful,” Gingras says.

For him, the web itself is in trouble.

“It’s so easy to drive the virality of content distribution that you can take a bit of spurious material and get a whole lot of people to accept it and believe it, so we end up therefore with the ability to create multiple silos of belief … multiple silos of alternate reality.”

And that is ultimately eroding the ability of journalism, and news media, to do its work as a bulwark of democracy.

“And so here we are in an environment where a company like Facebook dominates the web, and I don’t say this as a criticism, it’s a great product, but I don’t think we want a world that is dominated by proprietary platforms,” Gingras says.

But before publishers can lay the blame on the pernicious algorithms of evil tech empires, newsrooms are sometimes filter bubbles in themselves.

More than the disruption of technology to newsrooms, the ability of journalists to reach more people than the elites within which they are embedded is also key to ensuring a viable future for news publishers.

Google and Facebook need news publishers; they need content to keep users on their platforms, but they are also primed to become powerful publishers themselves, if they so wish.

“We’re not a news organisation, we don’t want to be, we don’t need to be — we connect the dots between knowledge and people’s interests. But we have a deep interest in the health of the ecosystem and the approaches we can take are, in a sense, architectural,” Gingras says.

Somehow, news publishers have to ensure our content contributions are compelling and viable, but also contribute to a better experience of the web.

“How do we, going forward, evolve models of journalistic storytelling to be more effective in a world driven by mobile devices?” asks Gingras.

One solution proffered by him, and echoed by others, is data journalism. Data journalism can be best understood as the amalgamation of traditional news-gathering techniques with the sheer scale and range of digital information now available.

But it is often an expensive exercise, especially for newsrooms that are already stretched.

“Twenty years ago, people were looking at video and saying that’s very expensive … and it was,” Gingras says. “It became less expensive when [the cost of] the hardware went down … it became less expensive as more people became simply capable of understanding what to do with it.”

A new initiative from Google will offer journalists across Africa training in skills such as mobile reporting, mapping and data visualisation, as well as verification and fact checking. In partnership with the World Bank and Code for Africa, the project aims to train more than 6 000 journalists by February 2018.

There is, though, an almost evangelical zeal attached to discussions about the value of data journalism for African newsrooms, a zeal that is sometimes discomforting considering the constraints newsrooms labour under.

Gingras acknowledges that ultimately it is us, as publishers of news, who will determine our future. “You don’t need somebody from Google telling you what to do,” he says.

The choice for publishers is simple — evolve or die. But we cannot risk being distracted by yet more shiny new things. Somehow we must be able to dabble with video formats and infuse more data journalism into our existing storytelling techniques, while at the same time ensuring that the value of journalism, the routine act of telling true stories about the world, is not adversely affected.