Religious groups fight back against a commission that does not hear them

The large room on the first floor of Soweto’s Orlando Stadium — filled with about 400 members of independent churches and religious bodies — erupts into ululations and applause as Prophet Samuel Radebe, head of the Revelation Church of God, enters.

“How do we trust such biased, abusive liars?” Radebe asks when he eventually addresses the gathering, mobilised by the All African Federation of Churches in response to what it sees as a bid by the state to control religion — driven by the Commission for the Promotion and Protection of the Rights of Cultural, Religious and Linguistic Communities.

In 2015, the commission began investigating the commercialisation of religion and the abuse of people’s belief systems.

The commission’s chairperson, Thoko Mkhwanazi-Xaluva, says the investigation was undertaken following “controversial news reports and articles about pastors [that] have left a large section of society questioning whether religion has become a commercial institution or a commodity to enrich a few”.

News reports have shone a light on preachers’ potentially harmful practices, including spraying congregants with insecticide and making them eat snakes or drink petrol.

The commission’s report, which has been tabled before Parliament, includes a recommendation that all religious practitioners be registered with the commission through an accredited umbrella organisation of their choice.

“This was necessitated by the fact that currently there is no comprehensive register where the communities can verify who is a bona fide religious practitioner … This register will also ensure that the religious leaders are compliant with the various laws of the country,” the report noted.

The recommendations didn’t sit well with those at Orlando Stadium on Saturday.

Radebe is a vocal opponent of the investigation. He refused to appear before the commission and ignored its request to view his church’s financial statements.

Guest speaker Liverson Mdongo kicks off the discussion: “Today we are gathered here in what is going to go down in the annals of history as a gathering of the religious community in protest.

“The report amounts to state control of religion. There should always be, in any democracy, a distinction between religion and state,” he states.

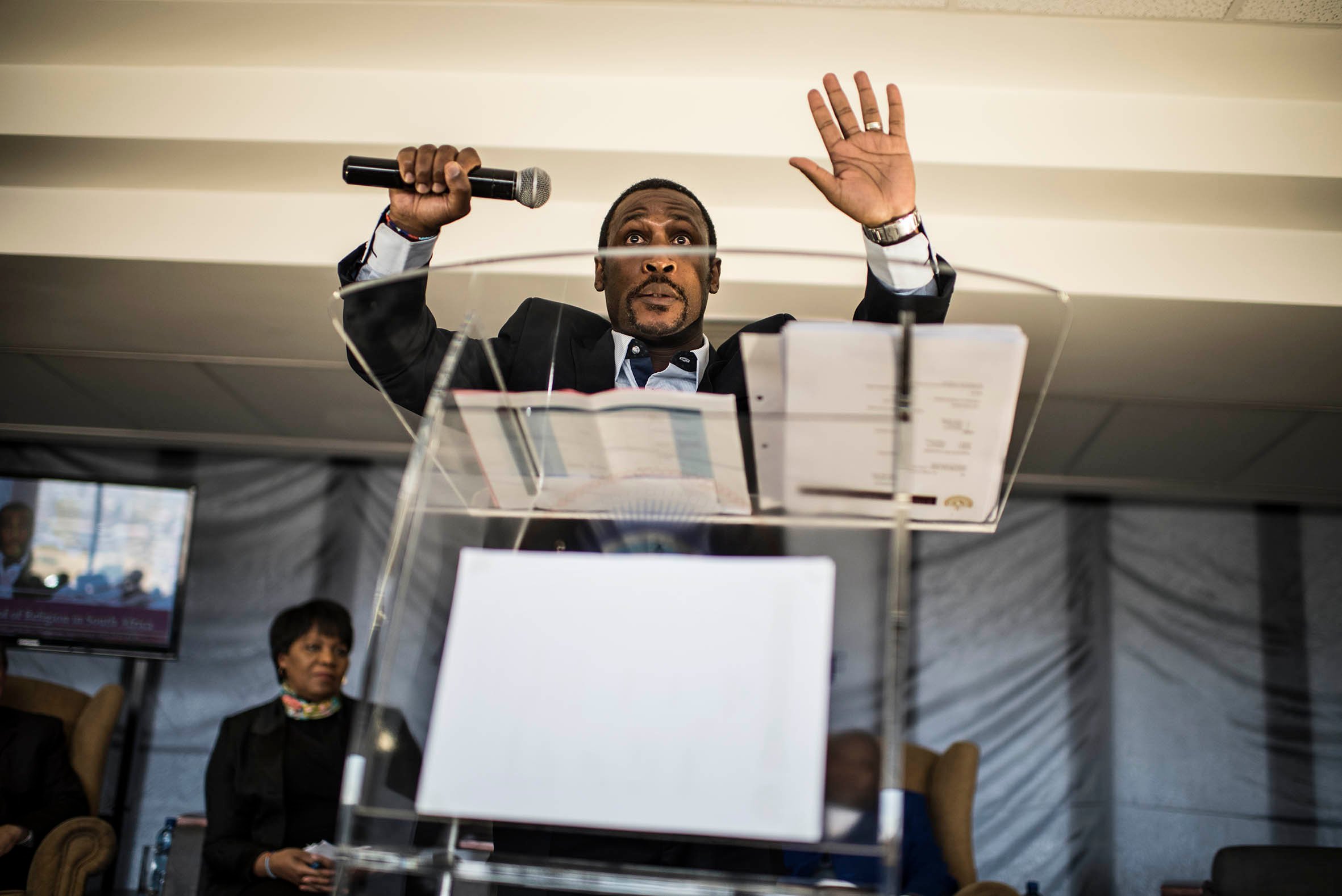

[Prophet Mboro addressing the Commission (Paul Botes/M&G)]

Speaking to the Mail & Guardian, Errol Jacobs, a pastor at Eldorado Park Believers, says the report’s recommendations are “demonic” and remind him “of the coming of the anti-Christ”.

“The result is that the commission — and by implication, the government — is on a collision course of conflict with the religious community. Our war is not against flesh and blood, but against the principalities and powers of darkness. We will … ask God to deal with them.”

Jacobs says that although the report highlights issues that are of “deep concern”, the commission has refused to have a constructive debate with the major faith groups and denominations.

“Instead,” he says, “they have chosen to sensationalise the handful of abuses — which the media profiled — to imply that all religious practitioners are at least potentially guilty of exploiting their congregations.”

Speaking during the debate, Michael Swain, executive director of Freedom of Religion South Africa, says: “It is not true that religion is not regulated.

“We live in a society that has the rule of law. We are all subject to those laws. Those laws are there for our protection. The problem is that these laws are not being enforced.

“For example, when you see somebody is being assaulted, you should call the SAPS [South African Police Service]. When someone has a prayer meeting for 20 people and the next day they bank R1.5-million, that is potentially money laundering — and you can’t hide that behind freedom of religion.

“In those instances, the relevant authorities should intervene. We have said from the beginning that the commission is the wrong organ to speak [on] this issue, because they are a state institution. It is up to [religious leaders] to keep our house in order.”

Favour Mary Stephens is the secretary general of the South African Union Council of Independent Churches. Speaking to the M&G, she echoes Swain’s call for self-regulation of the sector.

[Discussion during the Commission (Paul Botes/M&G)]

“Yes, there are people who are doing things that are not in accordance with the scriptures, but we would prefer there to be a regulatory body set up by churches themselves, not government. Government cannot regulate spiritual matters. We are directed by God. The Bible is our constitution.”

Edward Mafadza, the commission’s chief executive officer, has a different view: “The commission is a constitutional body … Nowhere in its recommendations does the commission say that the state must interfere in the religious affairs of any religion. Instead, the recommendations encourage self-regulation.”

He adds: “We are aware that the matters that the commission is dealing with when it comes to religion are not easy and we do expect some individuals to be uncomfortable.

“This is due to the fact that accountability … takes the powers back to the people that are being served, rather than the religious leader having absolute control over people.”

He says the majority of leaders in the religious sector and the majority of South African communities contributed positively to the report produced by the commission.

“The commission’s door is open for all faiths that genuinely want to drive the agenda of promoting and protecting the religious rights of communities.”

But it is not only independent Christian churches that have taken issue with the commission and its report.

Nokuzola Mndende is the founder of the Eastern Cape-based Icamagu Institute and says the commission does not value traditional African religions. “It still defines us like they did during colonial times — under ‘culture’.”

Although some of the institute’s representatives appeared before the commission during its hearings, “the final report does not talk about us. It talks about the privileged religions, like Christianity.”

Vuyani Cetywayo is the chairperson of Icamagu Spirituality, an organisation that represents traditional indigenous African religions.

“We appeared before the commission, but with the types of questions they asked us, it was clear that they were unfortunately using a wrong template.

“It was all about Christianity, not religion at large. So we have really lost interest in the commission.”

Cetywayo adds that the commission’s emphasis on requesting statistics on the number of people practising indigenous African religion increased their disillusionment.

“Most African people have two religions: their religion of choice, Christianity for example, and the one they were born with. And most of us perform rituals. It is more than just culture. That is our religion. We can’t quantify those numbers.”

Mndende, a former commissioner, adds: “The commission has existed for more than 15 years now, so can you say this is simply a lack of understanding? Or is it deliberate exclusion?”

But Mafadza says the commission is inclusive and “never meant to marginalise any religion, including traditional African religious leaders”.

Cetywayo says: “We have complied as much as we can … but the problem is we are not being listened to. No one wants to understand and hear us.”

Back in the packed room in Orlando Stadium, Radebe echoes this sentiment.

“We are not standing up because we are criminals,” he says. “We are standing up for our religion. Why are we not being listened to?”

Carl Collison is the Other Foundation’s Rainbow Fellow at the Mail & Guardian