'Finding grace during a time of political turmoil'

The year 1997 was important for the African-American hip-hop, pop and R&B scene.

It was the year Mariah Carey released her Butterfly album, which was discordant with the purist genre sensibility of straight R&B and pop. Her iconic collaboration with Bone Thugs-N-Harmony in their song Breakdown shifted the form and the trajectory of contemporary hip-hop hits so that the dulcet tonality of an R&B songstress matched and complemented the syncopated rhythms of a hip-hop MC.

Twenty years ago, a young, sex scandal-free Usher also released his album My Way, with singles such as You Make Me Wanna cementing the open silk shirt era in our Nineties’ imaginations — for better or for worse.

This was also the year Janet Jackson gifted the world with The Velvet Rope.

A departure from her five earlier works in sound and content, this studio album is heralded as an indisputable classic. The leading single of the album, Got ’Til It’s Gone, borrowing its chorus from the Joni Mitchell song of the same name, was released on September 22 1997 — exactly 20 years ago — marking a shift in Jackson’s career when she became vulnerable, honest and perhaps even more deliberately herself with her fans.

Although the song was not released as a commercial hit, it certainly created a sonic landscape for the latter part of the Nineties and embedded itself deep into the urban popular culture both abroad and here at home. Part of the reason for this relates to the music video, an overview of globalised blackness percolating in the interstices between African American and African life.

(Got ‘Til It’s Gone/ Janet Jackson)

Video director Mark Romanek places Jackson and Q-Tip in a make-believe world that emerges as strangely familiar. Despite it being shot in a theatre on Sunset Boulevard in Hollywood, there is a transience to this production that holds a quality distinctly African.

The ambiguity of this setting both in temporality and locale comes as no surprise, as Romanek is known and well acclaimed for his interesting cinematic choices. Before presenting him with the Video Vanguard award at the 1997 MTV awards for Got ’Til It’s Gone, Scream and others, Jackson introduced him by saying: “His videos lure you into a believable otherworld where natural, supernatural and provocative images exist.”

Got ’Til It’s Gone is set in a seemingly fantastical African locale, in which the city of Bamako in Mali has converged, entwined and populated itself with the residents of a Johannesburg on the cusp of apartheid.

[The video’s fantastical African locale (Got ‘Til It’s Gone/ Janet Jackson)]

Abstracted from the real world, sepia-coloured tones foreground this liminal place where the echoes of Mali’s post-colonial freedom and the oncoming repression of the South African state glide into one another.

This video encapsulates a brief moment when, perhaps in the early Sixties, black bodies quiver with desire and excitement and produce the kind of over-gesticulation and reckless abandon that is made possible by the imbibing of brown and clear spirits. The documenting of black joy, in spite of and perhaps even in resistance to, the “Europeans Only/Slegs Nie Blankes” signage is interspersed in the fictional building.

[The fictional building’s signage (Got ‘Til It’s Gone/ Janet Jackson)]

Images of young black men and women flash backwards and forward in between Jackson’s mellifluous vocals.

A man with a lighter flickering. Cutaway scenes of black boys holding each other close as they sway from side to side. This is a pure image of friendship, captured in embrace outside the imposition of terms such as “queerness” and “Other”, unable to castigate them into flimsy hetero-patriarchal relationships.

[Existing outside the imposition of heteronormativity (Got ‘Til It’s Gone/ Janet Jackson)]

The spectre of Joni Mitchell looms in a loop throughout the song as her voice crackles, singing the timeless hook “You don’t know what you’ve got till it’s gone” in conversation with Q-Tip’s “Joni Mitchell never lies” refrain. In the video, Mitchell’s face appears in concert with her voice on an old television set.

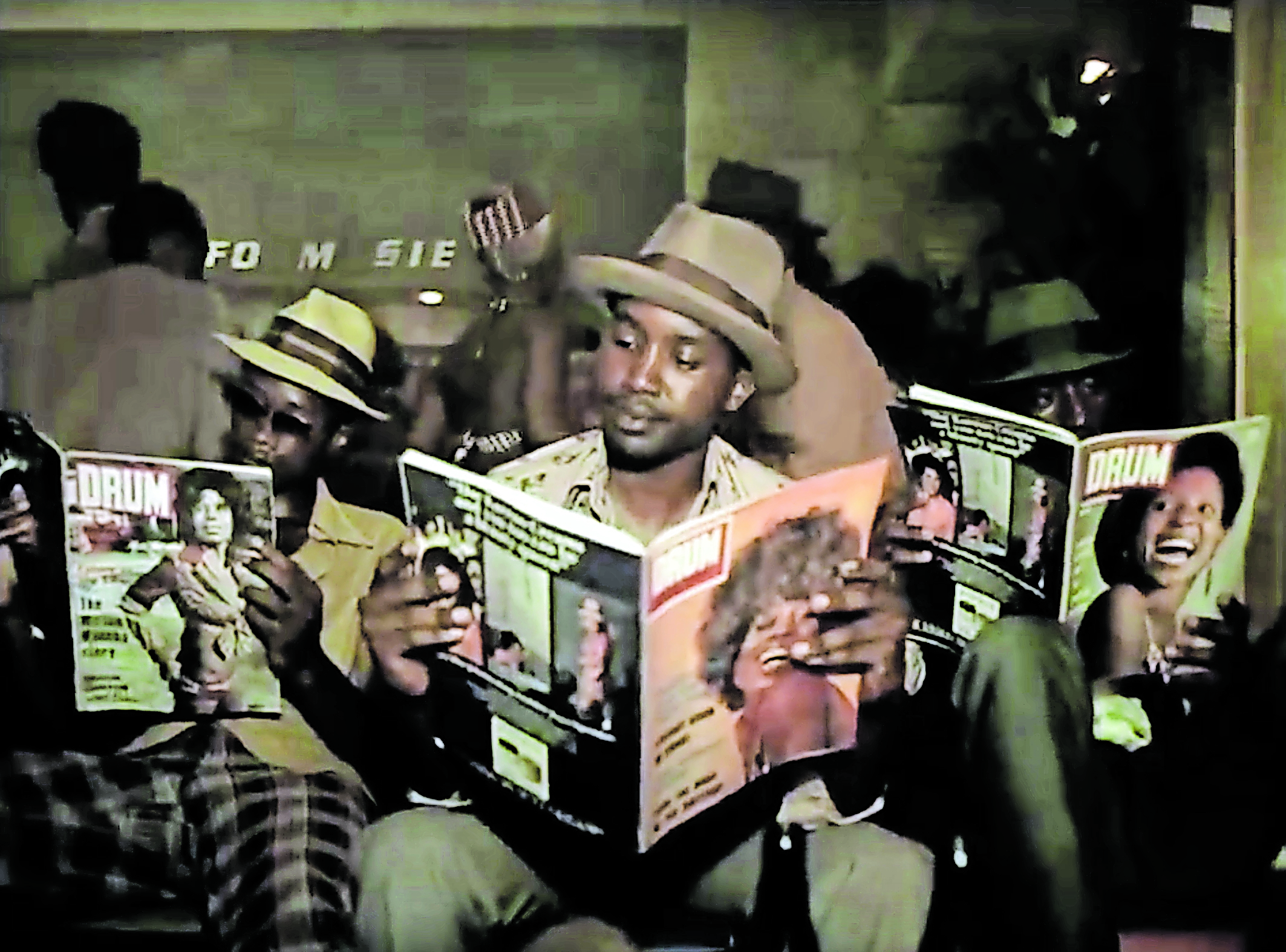

Some men hold out their identity documents as if asked for verification of who they are. Others pose with the latest issues of Drum and Esquire. A young couple peck gently at each other’s lips against a safari-themed wall. Exposed midriffs gyrate on the dance floor. Images of a young black boy thrown and suspended into the air by a crowd high on the euphoria of life. All of this black life squeezed into the confines of a music video that bursts at its own seams with sensuous joy.

Writing about the video, Marjon Carlos of Vogue remarked that “it felt like a scene straight from the work of Malick Sidibé, a Malian photographer who captured the fashionable mesh of modernity and tradition in postcolonial Africa in the Fifties, Sixties and Seventies”.

“Taking cues from Sidibé,” Carlos continued, “Romanek panned his camera over a gamely crowd who were finding grace during a time of incredible political and cultural turmoil, finally landing on Jackson, playing the role of the lounge singer, whose singular style and honeyed vocals had brought out the masses to get down.”

Romanek’s reference to Sidibé is masterful, as Sidibé’s portraiture was always inextricably linked to music, capturing on film the musicality of his subjects’ lives.

In an interview for GwinZegal in 2008, Sidibé said: “When you look at my photos, you are seeing a photo that seems to move before your eyes. Those are the sort of poses I gave them. Not poses that were inert or lifeless. No. People who have life need to be positioned that way.

“It was quite different at my studio.It was like a place of make-believe. People would pretend to be riding motorbikes, racing against each other. It was not like that at the other studios. That’s why my studio was so popular, already by 1964, 1965. The studio was a lot more laid-back.”

The trio of Jackson, Q-Tip and Romanek breathe fresh life into the image of this iconic studio, and Jackson’s nostalgic lament is of a time and a place gone by.

Twenty years on, Got ’Til It’s Gone — as both a cinematic and a sonic medium — can’t be referred to as dated or trite.

The same sensuous impulses that jolted us into a love affair with the immaculately lit black bodies of Jackson, Q-Tip and their troop of revellers continue to dazzle and delight our senses in 2017.