Mokonyane says exports recovered strongly, but that this was offset by contractions in household expenditure. (Reuters)

Health Minister Aaron Motsoaledi has warned that R20-billion in annual medical aid tax credits will likely be cut to fund the National Health Insurance (NHI). Your benefits may have just been granted a temporary stay of execution.

Werksmans Attorneys director of health and life sciences practices Neil Kirby says it’s unlikely that government would be able to effect changes to medical aid tax benefits in time for the start of the next financial year in April 2018.

Kirby was speaking at the Hospital Association of South Africa’s (Hasa) conference in Cape Town this week. Hasa represents private hospitals in the country.

Research produced by economic consultancy Econex found that scrapping the government subsidies could force 2-million people to drop private cover, says the firm’s director Mariné Erasmus.

Both Motsoaledi and former finance minister Pravin Gordhan have said that money will be re-routed from these subsidies and into the country’s NHI universal healthcare scheme. The NHI, which will entail a series of health reforms, is conservatively expected to cost almost R300-billion by 2025.

Listen: Motsoaledi explains why your tax credits are on the table

[multimedia source=”http://bhekisisa.org/multimedia/2017-05-24-motsoaledi-what-the-nhi-will-mean-for-you-and-your-tax-credits”]

How the NHI will be funded remains to be seen but Erasmus characterised the debate around its financing as one of the biggest distractions in conversations around the healthcare reform.

On paper, South Africa’s health funding looks pretty good, says Erasmus. The country spends about 4% of its gross domestic product (GDP) on public health, World Bank data shows.

At this rate, South Africa outstrips even Thailand in public health spending. South Africa’s NHI is modelled in part on the Southeast Asian country’s successful universal healthcare programme.

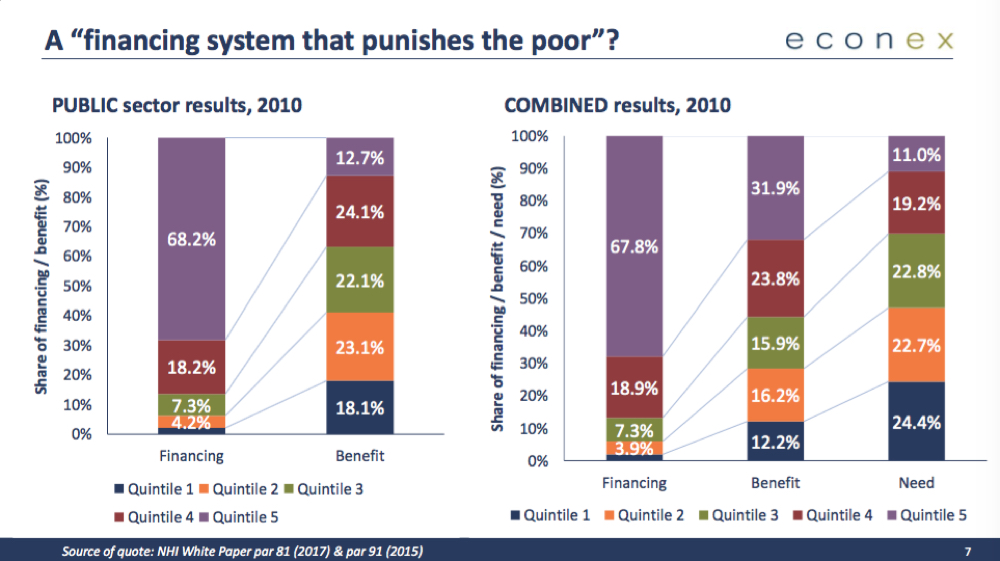

And South Africa even boasts healthy levels of cross-subsidisation in which wealthier citizen help pay for services for the poorer population, she says. According to an Econex analysis, the top wealthiest 40% of South Africans citizen are paying 85% of healthcare funding nationally: “They’re getting a little less than they’re paying for, that’s how all health systems work, but still get more than they need.”

When the same analysis was conducted on just public sector spending, the research firm found similar results.

“If you were to show me these statistics for any other country, I’d say it looks quite alright – people should be getting the services that they are paying for. But [in South Africa] the poor aren’t getting what the wealthy are paying for.

“The problem can’t then only be one of funding”, says Erasmus.

The answer to this riddle may, in part, lie in a recent report by the oversight body, the Office of Health Standards Compliance (OHSC). Between 2014 and 2015, the office’s inspectors conducted more than 600 appraisals of public clinics and hospitals across the country. Two out of every three facilities failed inspections.

Conditions were shocking. In one hospital, OHSC staff found sedated patients heaped onto the floor. Inspectors also documented instances in which health workers concealed expired medicines. In some cases, hospitals were found with medication that had expired three years prior.

Throwing money at problems like these won’t change them, cautions Erasmus.

“Why do [public health] facilities fail? The staff in the [private and public sectors] are the same, they work in the same sector, train in the same institutions, their patients have the same diseases…The only thing that I can think of is that leadership is problematic.

“One structural issue remains unaddressed: One of governance, management and accountability. If we focus on changing that… we may actually deliver better care since most of the funding seems to be there,” argues Erasmus, who gave input into the NHI white paper.

“But we’re focusing on a problem [funding] that is largely already solved. The public sector does not look the way it does due to a lack of funding. Structural problems need structural answers.”

A moment of reckoning?

That South Africa may not be able to blame the shockingly dirty toilets and collapsing ceilings of the public sector on funding alone may be one of the many harsh truths the country will have to face on the road to universal quality healthcare, warns actuary and University of Cape Town senior lecturer Shivani Ranchod.

At the hospital association meeting this week in Cape Town, heads of some of the country’s largest hospital groups and medical aid schemes pledged their support for the NHI.

“We cannot build a sustainable society and economy without ensuring the health of our nation. We recognise that given our shameful past in South Africa, we have created an incredibly unequal society and nowhere it that more evident than in the arena of healthcare. There is an enormous divide between the haves and have-nots and that gap is growing,” said Netcare CEO Richard Friedland.

Supporting access to quality healthcare is a no-brainer, according Ranchod. Deciding on how far you’ll go is another story:

“Of course we’re all committed to universal healthcare and the NHI because we care about human beings because it makes sense… because no one wants to see a neonatal intensive care unit without incubators.

“But to make a substantial change to any system is almost impossible to do without some sort of pain. We have to think about what is it as an individual and as institutions about what we are willing to give up for the system to change…whether we’re talking about land reform, employment equity or fees must fall.”

In the coming years, government will amend now fewer than 11 pieces of legislation to pave the way for the NHI and the health sector and consumers will have to negotiate these changes. Ranchod argues this should be through open, iterative processes that allow for conversation.

Because when it comes to the NHI, it may really be about the journey and not the destination, she says

“We have to get our processes right to engage in an open, honest way. We have to do something because our system is not good enough. South Africans deserve better.”