(Graphic: John McCann)

COMMENT

Many observers of the #RhodesMustFall and #FeesMustFall protests have been struck, or shocked, by the level of anger that welled up among the protesters and, at times, spilt over into verbal abuse and acts of violence, destruction and intimidation.

Insofar as this anger may be the most reliable indication of what motivates activism, it is important to fathom what underlies it — otherwise the most well-intentioned efforts to find solutions may be fruitless.

A number of reasons for the protests have been given. Moreover, it is clear that the protesters are not homogeneous, and different groups will have different motivations.

The reasons given include:

• Overt ones, given by protesters, focus on higher education — particularly removing financial and other material barriers and “decolonising” curriculums; and

• Covert ones, advanced mainly by analysts and government or political representatives — which point to wider social, economic and political factors. Examples of the latter include frustration with “enduring inequalities” and “the lack of change in post-apartheid South Africa”, as well as more specific political motives.

“The anger of student protests across South Africa [is] a symptom of the loss of confidence in Jacob Zuma’s government,” wrote Nathan Geffen on the GroundUp website last year.

Higher Education Minister Blade Nzimande said: “The ulterior motives are actually to destabilise the government and to mislead students for [the activist leaders’] own narrow political agendas.”

There is no way of knowing how such motivations are spread across protesters, but the implication is that the “narrow political agendas” exist primarily in the radical core groups.

In any event, my concern is with the anger of the majority of the protesting students who — though no doubt affected by social inequality — appear to be mobilised predominantly by the broad appeal to fight unfair obstacles to higher education, which directly affect them and their communities.

Their anger is rooted not only in the grievances already identified, but also in their experience of failure arising from obstacles that extend well beyond colonial curriculums.

Protests have been racialised, with the Fallist movements emphasising conditions and inequalities that are seen to affect black people in particular. It is thus justifiable and necessary for analysis of the issues to focus on black students, though always in the context of the system as a whole.

So far the issue that the protests have most strongly focused on — and that has attracted most public attention and precipitated unprecedented government response, with many billions of rands being “re-prioritised” to student financial aid in remarkably little time — is the demand for free higher education.

There is no doubting the significance of this concern for many students, but it is only government, not the institutions, that can address it.

So is the fees issue sufficient to explain the anger directed at universities?

Other major demands, particularly those concerning curriculum and institutional culture, relate to the students’ experiences at university.

It is accepted that institutional culture has a powerful effect on how positively students experience the learning process, and hence on their success. #RhodesMustFall was a manifestation of how emotionally charged this matter can be.

The demand for decolonising the curriculum can be seen in a similar light. But this demand is currently directed primarily at content — only one element of curriculum.

Moreover, the fact that there has been notably little specificity suggests that the protesters do not have a developed view of what decolonisation would entail across disciplines with diverse forms of knowledge. This may indicate that the demand is, in itself, symbolic of other, less-acknowledged, sources of alienation.

The question is: If a fully inclusive culture and curriculum could be achieved — assuming it would make a meaningful difference in fields such as mathematics, engineering, information technology and accounting — would this be enough to meet the students’ needs?

I believe not. My perspective, from three decades of working in educational development, is that for many black students in particular, anger with the status quo is strongly fed by frustration — and at times humiliation — arising from obstacles to their success in mainstream universities.

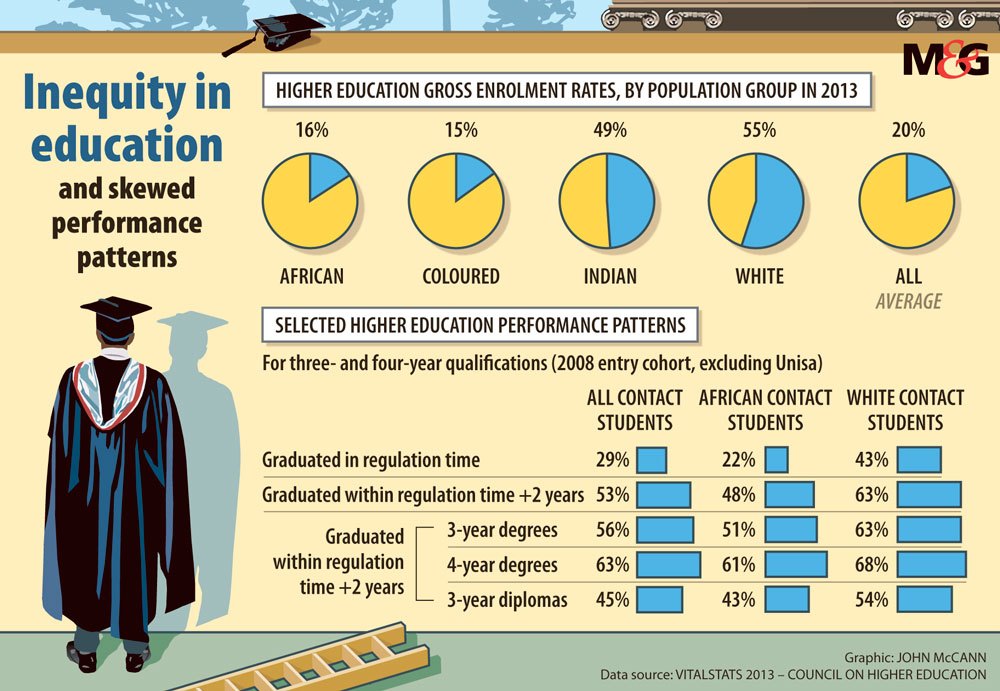

These obstacles affect students from all groups, but have a disproportionate effect on African students, as illustrated in the graphic.

Equal access to higher education — in the sense of gaining a place in a university — may appear to be close to realisation, but this is illusory.

Black student enrolment reached 70% of the total in 2013, yet participation rates (indicating the proportions of the different population groups getting into higher education) show a different picture — major racial skewing against a backdrop of low overall participation relative to other countries.

The gross enrolment ratio indicates total enrolment as a percentage of the 20- to 24-year-old population, so, in fact, only about 12% of African and coloured youth are entering public higher education. Protesters are right that access remains a major problem.

Because those entering university are generally among the best achievers at school, the African and coloured youth in higher education represent a small “elite” with high potential to succeed. But there is something seriously wrong in the system in this regard. Access without success is a hollow achievement. The figures in the graphic highlight key aspects of what is being achieved.

No group is doing well. The graphic shows only African and white performance rates, but coloured and Indian performance invariably falls between these. It is only in the “elite” four-year degrees that the completion rate after two additional years exceeds 60%. Department of higher education data tells us that nearly half of all students entering universities are not graduating even within 10 years.

The continued racial skewing in performance compounds the inequalities in participation rates. The consequence is that only about 7% of African and coloured youth are succeeding in higher education, and the gains made in black enrolment are largely neutralised by limited success.

The performance patterns reveal a near-tragic irony for #FeesMustFall — the access that is being fought for is access to only a 50% probability of succeeding. For National Student Financial Aid Scheme-supported students, the probability is closer to 40%.

Although success has not been an overt element in the protests, research shows that students’ academic performance can have a major effect on their productive engagement with their university. It is most likely that the low and skewed completion rates significantly underlie student disaffection.

The predominant reason people go to university — and why families and communities often make sacrifices to enable this — is to succeed, to gain a qualification that will improve their lives. So failure at university is deeply demoralising, and is often bewildering because the reasons for failing are not clear.

These students commonly experience self-doubt, anxiety and frustration, which can become anger and suspicion, or a heightened consciousness, of institutional discrimination. What is more likely to cause alienation from an institution than frustration of one’s core purpose for being there?

The current performance patterns may well become a major overt source of student dissatisfaction. If equal access is realised, will a focus on equal outcomes be far behind?

The political demands of the movements create a major risk that all available funding will go towards student financial aid. Even if accompanied by attention to institutional culture and curriculum, this would by no means accomplish substantial improvement in the outcomes of higher education.

The need for such improvement lies not only in satisfying student demands, but also in giving due respect to the intellectual potential and the educational aspirations that exist in all our communities.

More detailed analysis of the obstacles to student learning, and how they may be addressed, will be published next week.

Emeritus professor Ian Scott is the former director of the University of Cape Town’s Academic Development Programme