Ratings agency Moody’s downgraded Steinhoff’s credit rating by four notches three days after Jooste stepped down.

In just days after the Steinhoff saga began to unfold rapidly, a few investigations were initiated but many more fingers were pointed, and several parties could have a case to answer. But could anyone have seen it coming?

In fact, some did. Not least is Futuregrowth Asset Management, which has not had any exposure to international retailer Steinhoff for several years.

Its chief investment officer, Andrew Canter, said, although fortuitous investment decisions are often just a fluke, the decision to reduce Futuregrowth’s exposure to Steinhoff to zero was not luck.

“There was enough anecdotal or circumstantial evidence there to tell you, as an asset manager, to either dig deeper or leave it alone.”

Canter decided to end Future-growth’s exposure to Steinhoff in 2009, after having invested in the company for many years. Futuregrowth, the largest bond investor in Africa, had also limited its exposure to African Bank before its collapse in August 2014.

The decision to drop Steinhoff went against the trend. The company had long been a stock exchange darling and, according to market evaluation, was the seventh-largest company in the JSE Top 40. As such, many funds that held the index automatically held Steinhoff.

The market largely bought into the company’s management’s assurances that an investigation into its tax affairs in Germany would come to naught and also did not show overt concern that the company’s auditors had refused to sign off on its financial statements before their release.

But when the Steinhoff chief executive, Markus Jooste, stepped down last Tuesday night in light of so-called “accounting irregularities” and it became clear the financials would not be released, investors realised that the company was not in as good financial health as it purported to be and the share price tanked from R65 to R5 in a day.

For Canter, there were four things that informed Futuregrowth’s decision to divest.

Complexity

With dozens of companies and products in several jurisdictions, the business was enormously complex.

“As a lender, it becomes virtually unanalysable; you are just not able to understand. So you have to take a view of whether it’s intentional or just due to the nature of the business. We took a value judgment that it was intentionally complex. In our view, it was a seemingly wilful desire by management to create opacity. They would say: ‘It’s complex. Just trust us.’ As a lender, that doesn’t work for me.”

Serial acquisition

The company had a high rate of acquisitions.

“They just never stopped buying stuff. That sort of behaviour, serial acquisition, it’s a textbook warning sign. It also means you can’t compare last year’s results with this year’s results. So you never have a base to determine whether the company is well run or badly run.”

Past dealings

“Years ago, we had specific dealings with how they interpreted the terms of a listed bond agreement. I could see their approach was more liberal than we were comfortable with. When we challenged them, there was a very unfriendly response. It taught us this was not a company that in a sense respected their lenders,” Canter said.

Bad vibes

Various reported allegations cast Steinhoff and its affiliates in a negative light over the years. Many people will remember how chairperson Christo Wiese was stopped at London City Airport en route to Luxembourg with bags full of cash, which he explained as originating from diamond deals in the 1980s and 1990s.

When Steinhoff acquired Pepkor, there were allegations that Wiese had bought shares during a period when dealings should have been closed.

In October this year, the Financial Mail did a profile on Jooste, who revealed the company had already set aside money in anticipation of what the German authorities might find in its tax investigation.

“At the end of the day, what will happen will happen and we are more than adequately provided for,” Jooste was quoted as saying.

Canter said: “There have been periodic allegations over the years of aggressive tax and accounting practices, as well as hints of other possible impropriety. Equity investors just don’t seem to pay attention to this kind of thing.”

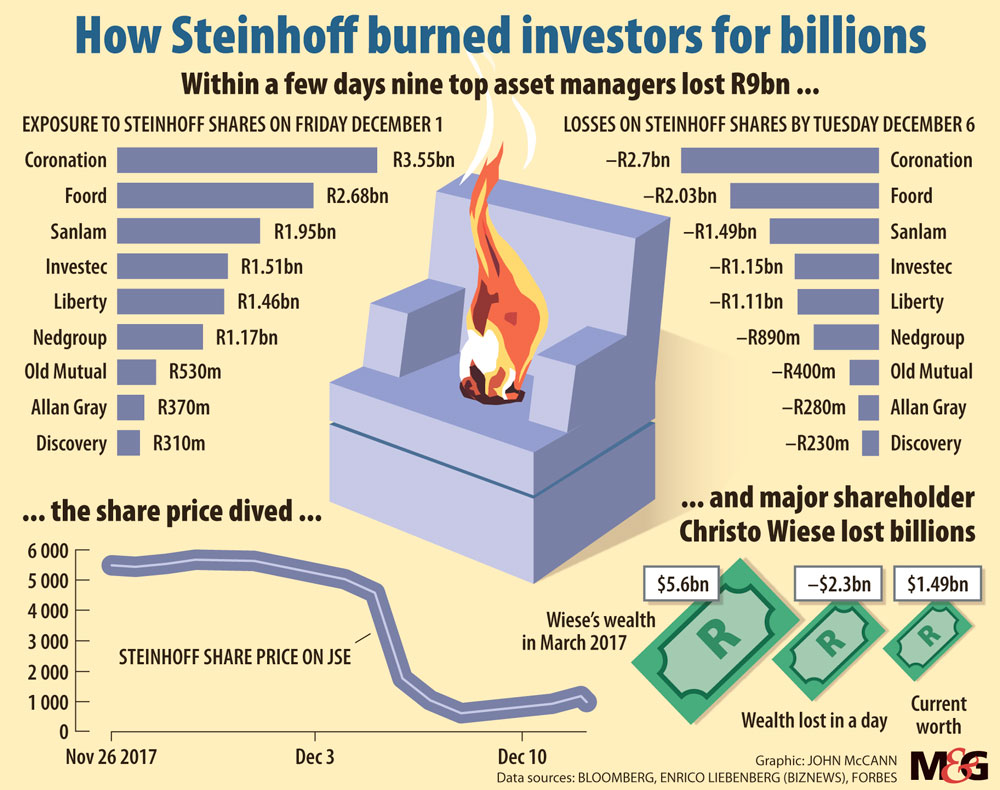

Many prominent asset managers were exposed to Steinhoff and took a substantial knock. According to estimates by chartered accountant Enrico Liebenberg and published on Biznews.com last week, the most exposed of the major fund managers (and thus the biggest losers) were Coronation, followed by Foord, Sanlam, Investec, Liberty and Nedgroup.

The Government Employee Pension Fund, managed by the Public Investment Corporation, held about R28-billion in Steinhoff International Holdings, roughly 10% of the company’s shares but 1% of the total assets of the fund. Estimates put the possible losses in the region of R15-billion to R17-billion.

The exposure of local banks that lent Steinhoff money is not yet known although estimates of their debts range up to R240-billion, according to Business Day.

Magda Wierzycka, the founding chief executive of Sygnia Asset Management, questioned how asset managers did not pick up clear problems with the company, which she said she found within 30 minutes of reading through Steinhoff’s financials.

But shareholder activist Theo Botha said he was sure that everybody had probably trawled through the financials. Asset managers asked questions behind closed doors and tended to be quite tacit, he said, “and, of course, [chairperson and billionaire] Christo Wiese was flavour of the month”.

But there are other parties who could be called to account.

Steinhoff’s board and its directors are already in the sights of the Companies and Intellectual Property Commission (CIPC), which on Tuesday announced it would investigate allegations that relate to noncompliance with the Companies Act and regulations.

This follows an announcement last week that the Financial Services Board has instituted an independent investigation into possible false and misleading reports, and possible abuses in contravention of the Financial Markets Act.

The JSE also has launched an investigation to determine whether there have been any breaches of its listing requirements, including in relation to previous financial disclosures made by Steinhoff. It is also reviewing trades in the share before the company’s announcements, which preceded the share price crash.

But Botha asked why the company’s shares had not been suspended from trading altogether. “With African Bank, the share tanked on Wednesday and, on Friday, they suspended trade,” he said. The Steinhoff share should be suspended as shareholders are able to trade recklessly at the moment with no information whatsoever.

“Surely the board is being irresponsible and the JSE is also being irresponsible,” he said.

After crashing to R5 a share last week, the Steinhoff share on the JSE lifted to R9.80 on Thursday.

The JSE said this week it had decided to allow the share to continue to trade because the company has disclosed as much price-sensitive information as it is able to. Also “it would be detrimental to the interest of investors to prevent them from trading Steinhoff International shares on the JSE when it is not suspended on the Frankfurt Stock Exchange”, it said in a statement.

Ratings agency Moody’s reacted, downgrading Steinhoff’s credit rating by four notches three days after Jooste stepped down.

But, ultimately, many of the parties called to account will likely say they relied on the financial statements signed off by auditors Deloitte in past years.

The firm said it is unable to comment because of client confidentiality and the ongoing investigations.

The CIPC this week asked the Independent Regulatory Board for Auditors (IRBA) to look into the matter.

The issue is complex because the details of the collapse remain unclear and the matter is a multijurisdictional, so the board still needs to consider its role, said Bernard Agulhas, IRBA’s chief executive.

Steinhoff’s primary listing is in Frankfurt and it has a secondary listing on the JSE. The company is incorporated in the Netherlands but operates in several jurisdictions.

Agulhas said “accounting irregularities” also do not necessarily indicate an audit failure, as accountants and auditors have different responsibilities with respect to financial information. Also, different structures have oversight over accountants and auditors.

The South African Institute of Chartered Accountants, a professional body, has oversight of chartered accountants, such as Jooste, but it does not have investigative capacity and has to rely on the outcomes of other processes, which may take years, before it can take action.

For example, Leon Kirkinis, who headed African Bank at the time of its collapse, remains a registered chartered accountant while an investigation into the then auditors of the bank continues.