Works by Mawande Ka Zenzile: Cash Cow

A Facebook post I happened to scroll past in January aroused my convictions that even if it takes millenia, there will come a time when science will need to extend its epistemological limitations and consult the hidden wisdoms of the knowledges it has done so well to demolish. Allow me to paraphrase it: stop being ignorant by praying for rain. Just use less water. Prayer is not going fix the water crisis but practical things such as using less water will.

[‘Sibhala Sicima’ a work by Mawande ka Zenzile (Courtesy of Stevenson)]

In December last year, my mother and her friend ant’Nomathemba came to Johannesburg from East London to attend an annual choral music festival. Every year, they stay with me and each morning I take them to the festival and pick them up in the evening. On the third morning of their visit, as the three of us were getting ready to leave the house — three different perfumes permeating the air — my mother remembered that she had wanted to tell me a little story.

The story goes that a longtime friend of hers has a farm near a small town in the Eastern Cape and on this farm there are some cattle among other livestock. Towards the end of last year, one of the cows broke its leg. (There are no veterinarians in the area and, as you are about to find out, there has not always been a need for them.)

My mother’s friend, upon learning of the cow’s broken leg, called the local dude you call when your livestock, impahla yakho or your wealth as they say in isiXhosa, is sick. The man agreed to come to the farm to see the cow and said he would need four men to assist him.

Two men would have to hold the cow’s horns while the other two would stand behind the cow during his examination. He said he would arrive during the day when the sun would be directly above them.

When he arrived, he was carrying a long syringe-like contraption, which my mother’s friend assumed he had made, that had plant medicine inside. He asked the men to isolate the cow in the kraal, take their positions and explained that the cow needed to stand in a way that it made a shadow of its body inside the kraal. When everyone was in position, including the cow, which could not walk properly, he approached the animal carrying his instrument.

What happened next surprised even his assistants and other spectators. The man took the instrument and pointed it not at the cow’s leg, but at the shadow of the cow’s leg. He then injected his plant medicine directly into the shadow of the cow’s broken leg, in other words, into the ground. When he was done, the men retreated to let the cow get its bearings. They then watched as the cow slowly started to move its leg, as if it was trying on a new shoe. After a few seconds, it started to walk further and further away, until it regained its gait. It was only a few days later that he returned to put a bandage around the cow’s leg so that the muscles would heal correctly.

My mother’s question at the end of the story was: “What is African knowledge and where does it belong today?”

When we heard this story, I could not believe my ears but ant’Nomathemba could. She sat down on the bed next to my mother and told us that when she was growing up in Ngqamakhwe in the 1960s, whenever inkanyamba (a tornado) or another vicious storm was on its way, the people of her village knew how to redirect it.

When the storm was approaching, everybody would get out of their homes carrying the loudest object they could beat. People would come out with pots, pans and drums and wooden spoons or pins to bang them with. All the twins and triplets of the village would be sent to the front of the large group and the older men would stand at the back. Everyone from the women to the men, boys, girls and grandmothers would beat their pots and drums as loudly as they could, looking towards the storm shouting eeeeeeeeeeMbooooo!!! eeeeeeeemmMboooooo!!! eeeeeMboooooo!!!!

eMbo is what abaNtu believe to be The Source, the place from whence we come and the place we shall return.

Ant’ Nomathemba said her grandfather would stand at the back of the crowd, chew on a particular root, which she named, and then spit the root out towards the storm also calling out to eMbo! After a short while, people would return to their homes and wait. Each and every time, she says, the storm would retreat or change direction and head for another village.

In my perennial need to make sense of life, six months ago I reached a threshold when it came to unpacking my physical identity — my race, ethnicity, gender, class, geography, sexuality. At some point when I was deep in my wokism and none the wiser, something required me to explore my invisible or non-physical identity for me to continue on the path of healing, acceptance, self-knowledge, wholeness, ubuNtu.

Because we are not just intellectual, emotional and physical beings, I knew that I needed to go in a direction where my political practice would be informed by a complementary spiritual knowledge and practice. So I started hanging around the intangible territory of knowledges that can loosely be termed as African knowledge systems, a local branch of universal Indigenous Knowledge Systems. Here I found a world that has always been there. A world that Africans and other indigenous groups around the world have had access to and routinely live within, in addition to living in the “developed world”.

In the “developed world”, knowledge is limited to what the five senses can conceive of, understand and explain. Anything that science cannot explain is often dismissed to the realm of the “superstitious” and because it cannot be explained in empirical terms, is delegitimised as a form knowledge. This is a problem that the developed world does not even know it has.

African knowledge systems for instance, are not known for being so insecure as to suppress other forms of knowledge that they do not understand. When you consult a healer for something, he or she can usually detect that something is painful in your chest region without touching you. After diagnosing what this could be, he or she almost always encourages you to go to a medical professional for more knowledge and understanding of the problem.

A medical professional, on the other hand, if after thorough research does not know what is wrong with you or if they are unsure, is legally barred from encouraging you to seek the help of an indigenous healer. Similarly, African spirituality does not limit one’s spiritual expression to itself only. It is not frightened when people want to learn about Christianity or Buddhism in addition to their African spiritual practice.

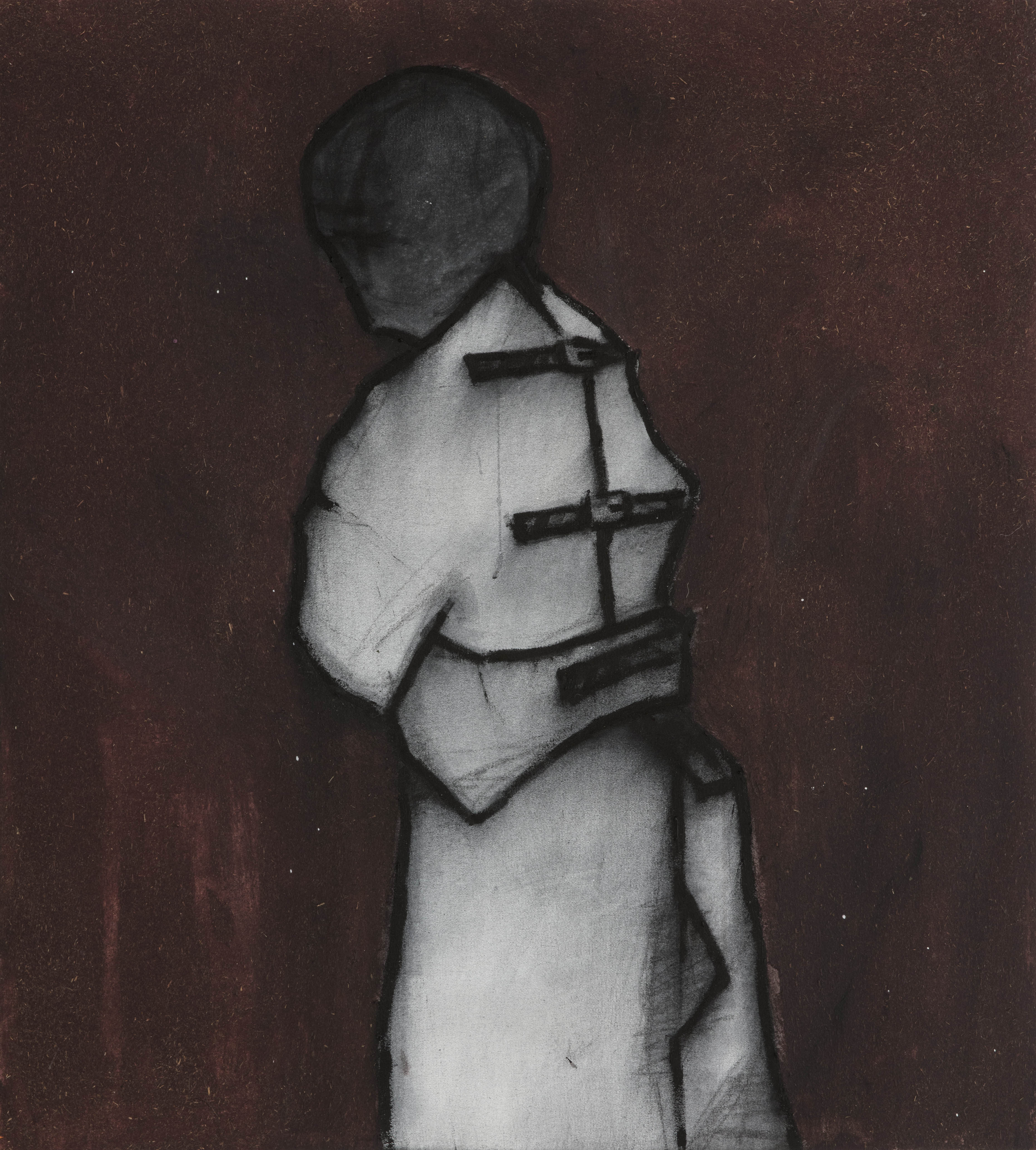

[‘Crazy’ a work by Mawande ka Zenzile (Coutresy of Stevenson, Johannesburg and Cape Town)]

But there seems to be this idea that if you are Christian you cannot and should not practise your African spirituality. That you need to choose one and stick with it. In both these cases, who is disadvantaged by the deliberate withholding of knowledge? Is it not ultimately all humans?

It’s true that one of the biggest issues facing African knowledge systems today is the lack of standardised practices. If a healer correctly diagnoses you with a stomach ulcer, there is usually no scientific way that they can explain how they arrived at that diagnosis, even though it is correct. One healer might feel it on their person and another might be shown a vision. This is a crushing impediment to the demystifying and normalisation of African knowledge systems, an impediment that has worked brilliantly for the slower advancement of human evolution through science only.

The classification systems we use today, which certainly make our modern lives easy, are colonial practices born of a school of thought that requires the mysterious to be captured, structured and organised in order to become legitimate knowledge. This is often in very particular ways such as laboratory-led science, scientific medicine, printed literature or anything tangible to the senses.

Although Western knowledge has produced incredible feats of progress for us as a species, it has not always been reliable or true yet it is still the main form of legitimate knowledge. It has informed laws that have governed the world as we know it and yet many of these man-made laws have had to be revised every couple of decades because of this unreliability and a fundamental lack of universality.

Any form of knowledge that lives outside of what is understood scientifically is not only ignored, not funded and not developed, there is a hostility towards the unknown that, at best, displays a fundamental immaturity and a lack reverence for life and, at worst, slows human evolution.

What has this meant for the development of the intellectual, philosophical and spiritual expressions of African knowledge systems in the last five centuries? Furthermore, what has this meant for the development of human knowledge generally? Without taking away our own agency and role in the colonial project, Africans have been dislocated from their lands, forced into labour often far away from home and limited to being teachers, nurses, clerks, domestic workers, drivers, gardeners and builders. This under the devastating yolk of a Christian civilisation that has thrived by ordering us to denounce our knowledge systems. So what has happened to those knowledge systems?

In the absence of a liberated people through which they could be expressed, did these knowledges disappear, hide, become dormant or reduce their modes of expression? All of these are possibilities.

But perhaps the cows are beginning to make their way home.

For a long time, many Africans have had to hide their knowledge of these knowledges. Their power. To survive in the colonised world. But today, freedom of movement, self-determination and life is not what it was in 1913. Today, Africans have survived and gained other knowledges and become professionals such as doctors, engineers, scientists, judges, lawyers, architects, artists and writers in addition to their suppressed African knowledge systems.

If those suppressed knowledges are freer to emerge today, does this not explain why our professionalism has not stopped some of us from getting spiritual or ancestral callings to thwasa even though we are doctors, lawyers, judges, accountants, teachers and writers?

Does this not make us perfectly hybrid beings, adept at being African and Western?

I believe in the universal law of balance. We may create our own rules to make sense of the world but the universe has its own unchanging system of laws that determine the evolution and survival of the earth and life.

If we acknowledge land as a living cosmological unit of the universe, something intrinsically linked to the consciousness and survival of all sentient and natural beings, if we acknowledge that land is not just something to build property on and create views of, then we can understand that the land does not forget what has been done to it.

And thus, I think there is another way to enter and understand the water crisis that has resulted from the drought in Cape Town. As it becomes increasingly clear that science and Western knowledge systems are not the only forms of knowledge, it’s important to consider that this drought might have little to do with meteorology and more to do the cosmological relationship between land, human behaviour and universal laws.

If my Facebook friend had made his statement while living on another continent — one where people have never summoned rain by playing their kiba/dinaka drums, where there was no rain queen, a place without its own intrinsic knowledge systems — then his statement would be irrefutable.

I don’t blame him though, as much as I want to. His regard for anything he can’t explain was trained in Helen’s colonised Africa, as was much of what is today considered legitimate knowledge.

The goal, though, is not to pit one knowledge system against another. The role of knowledge is to be of service to our lives on and in relation to the earth. It is to be shared, exchanged and expanded for the greater good of our species. When existing knowledges are deliberately ignored and expunged, everybody stands to lose.