Making Exiled: "I think there was a lot of intuitive energy at play in making this music

Exile.

Noun.

The state of being barred from one’s native country, typically for political or punitive reasons.

Exile.

Verb.

The act of executing the same.

Pianist, composer and singer Thandi Ntuli has termed her sophomore album Exiled and she did this with the understanding that real life is never quite as simple as a dictionary definition. Instead, it is nuanced. It is lived. And so, it is fundamentally different.

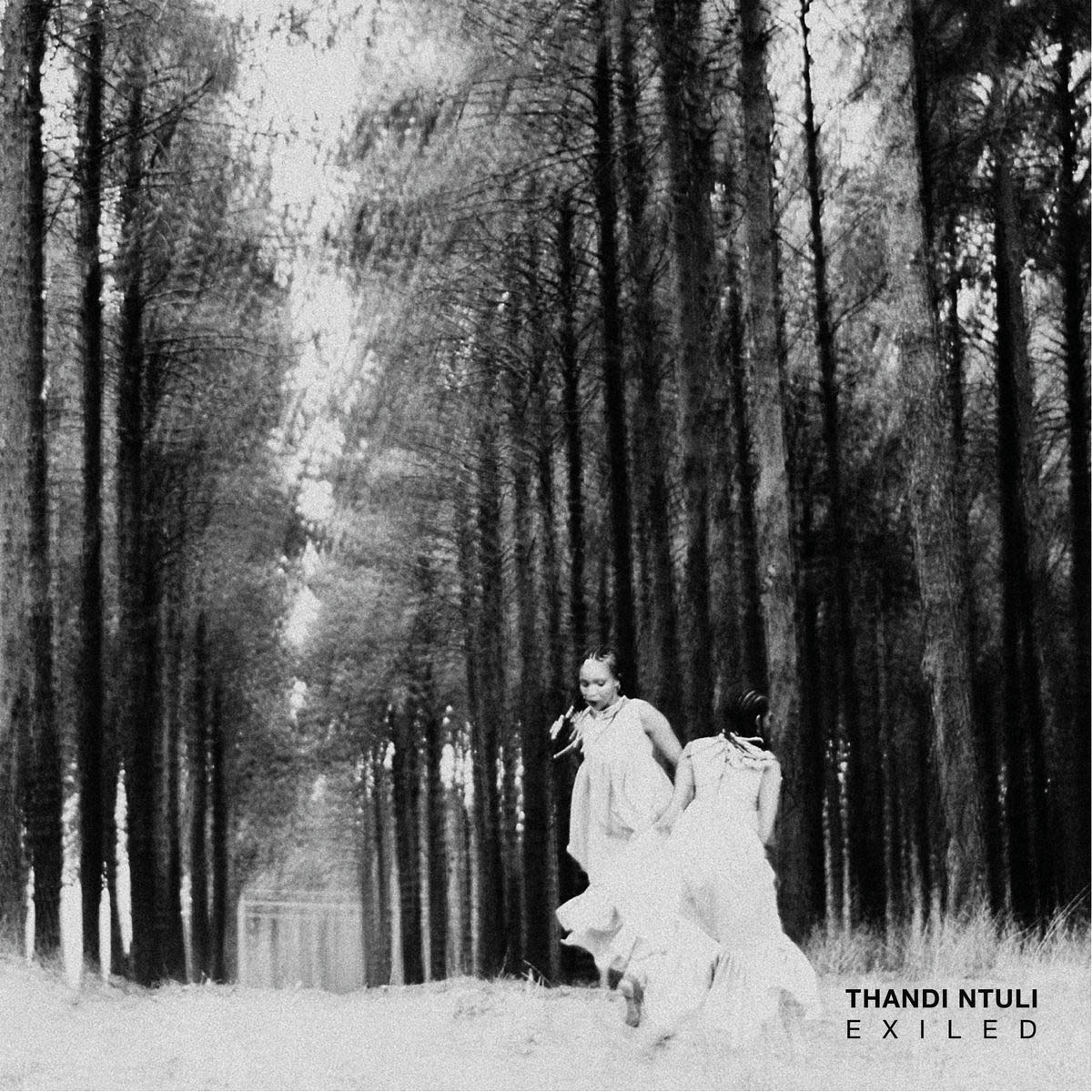

[Thandi Ntuli’s sophomore album Exiled (Cover: Ndlela Music Company)]

Ntuli curated the album’s flow by letting it build organically.

“It goes back to the fact that when I was creating the music, I didn’t create the whole concept. It sort of strung itself together. The use of the word ‘exile’ explored different meanings as the album came together. I thought it would be useful to use that word as it works so particularly for South Africans,” she says.

In 2014, after 26 years of taming the keys, she plied them for the celebratory salutation of The Offering. Now aged 30, that alchemy has yielded the masterful Exiled, a transformative work.

Like her debut album, she released this one independently, under her label Ndlela Music Company.

The launch was held at The Orbit in Braamfontein, Johannesburg, on Friday April 13. Superstition aside, Ntuli’s performance was not only a revelation for her audience but for the musician as well.

“It was so packed. I don’t think I’ve ever played at The Orbit and had it that full. People were standing. There were some people sitting by the steps of the stage … I enjoy that feeling of, you know, people communing around the music.”

Her thinking around the launch saw the concept of exile being articulated in more than the music.

“There’s lots of visuals that accompany it, and lots of writing — even stuff that was not included in the album … I put that together and I think people received the show well. It also connected the entire performance. As an artist, one of the biggest things I’m always sort of concerned about is: Will I be misunderstood? And I felt like everyone really understood, which was very rewarding and fulfilling for me. In that sense, the gig was totally beyond my expectations.”

Sense of displacement

The country’s history includes a significant exodus of its most valuable jewels prompted by past political climates. Families were broken apart. Circumstance forced locals from their homes, their origins, their ancestral bearing. Living out their lives in alien spaces where assimilation meant adopting an unfamiliar culture. An intentional loss of self for the sake of survival while still clinging to home.

Ntuli taps not only into the political but also into the personal. Because the word “exile” could never express just a singular form of ostracism. Of loss. Of going to pieces.

“There were ideas I was playing around with, exploring, which were intermingled. Questioning how black love exists, for example, within our families. Looking at spousal relationships, how black love exists within ourselves … My perception was that there’s some sense of exile still. Even though we’ve passed political emancipation. There are a lot of things which still feel displaced, even though we can’t put our finger on it.”

Ntuli says this led her to put Cosmic Light at the end of the album, as a sort of conclusion. It’s an ethereal composition. Benji’s Meditation surrenders itself as a prelude that sighs into the last track. The piece looks at the various versions of exile that people wander through, and how this journey doesn’t escape spiritual exile.

The violence of black lives

Voodoo.

Noun.

A magical practice combining ritual, religion and tradition characterised by sorcery and spirit possession.

Ntuli, high priestess, conjures with composition. The album art is eerie. The music settles like a veil, colouring the way you take in the world. Bold. Beautiful. Even brusque in places. It lingers like scenes from an X-rated horror movie that show up in staccato. On the screen for a split second, leaving you doubting what you’ve seen as the impression remains.

“I started writing the music for the album maybe late in 2015, early 2016. In that period I was going through whatever process I needed to bring it to life. And if I hadn’t been doing what I was doing, I wouldn’t have been comfortable with the music or how it would come about,” she says.

She jokes about 2015 being a pivotal period in her career and suggests that maybe we will see a song named after the year on her next album.

Near the end of 2016, Ntuli attended a talk that had local poet and writer Mongane Wally Serote behind the mic. She recalls straightening her spine when he said: “The story of black men in South Africa is a story that needs to be told.”

On her album, the concept of black love plays itself out in an intricately quirky and upbeat contemplation called Complicated, on which she and fellow vocalist Vuyo Sotashe banter playfully. The melody has two parts because black love can’t be expected not to spill over. Black love could never fit into a single rendition.

“I always felt that there was a link between how apartheid meddled with the black family … There’s never been a time for black men to have a chance to be tender. A lot of the way that black men relate to black women now can be based on that,” she says.

She adds that, based on the stories that Serote shared with her, she was able to stand in the unequivocal certainty that the basis of black lives has always been a violent one.

“The violence also existed within the home. Black man to black woman. Black woman to black man. Maybe it’s with understanding that we can start healing.”

She adds that too often in this country we remove social issues from the past. We talk about violence in isolation, instead of applying sankofa — an Akan term that literally means: “It is not taboo to go back and fetch what you forgot.”

Ntuli believes in excavating the past and applying its teachings to make sense of the present.

She tackles the theme of broken black boys in The Void, in which poet Lebo Mashile asks: “What happens to black boys who go missing? Do we even call them missing or do we just say he is gone? What happens to boys who learn to die inside their skins the day they learn what their fathers have done to their mothers? What their mothers have done to themselves?”

An anxiety that permeates

Something is wrong. There’s an insidious stranglehold that has dug its tentacles into the collective hearts of the youth. It squeezes. An incremental tightness closing in.

It manifests in ways that debilitate mentally. Physically.

It silently crushes. It feels like there’s no getting out from under it. No getting away. No way out.

In the documentary Generation Anxiety, British singer-songwriter and pianist Laura Mvula admits to the struggle she has been carrying.

“I still think there’s a huge part of me that still thinks: If you were to open me up and look inside, you’d find something terribly wrong, that’s not fixable,” she says.

Ntuli agrees: “We struggle a lot with anxiety. As much as folk are saying that what happened in the past is over and everything is equal now, it’s not necessarily over.”

A possible solution, she says, is “to be kinder to yourself and recognise it’s not due to lack of your initiative that things aren’t going your way”.

Perhaps, in recognising this malaise, Ntuli saw a need to bring forth some sort of alignment for herself. A fix. So she began a journey in 2015 that has served her and her music.

“Namaste. I bow to you. The spirit within me salutes the spirit in you.”

Among other things, this ancient Sanskrit greeting has been incorporated to signify the beginning and end of yoga sessions.

Ntuli says she was introduced to yoga at university but never stuck with it. That was until she read a Wayne Dyer book. He was a philosopher, self-help author and motivational speaker. And that’s when it occurred to her to change the way she had been practising yoga.

Initially, she would watch videos online or move into poses and breathe on her own. But in September 2015 she took to attending studio sessions and claims that the environment was good for her. She’s since witnessed a change in her wellbeing.

“The yoga has helped me emotionally, with my mental focus and my ability to be singularly in one place.”

She adds that she doesn’t think she stresses or freaks out nearly as much as she did in the past. “One thing I’ve learned through yoga and meditation is being at ease in whatever discomfort I find myself in,” she says.

This type of lifestyle overhaul —especially one existing on such a spiritual level — has also influenced her artistic process.

On creating Exiled she says: “I think there was a lot of intuitive energy at play in making this music. It took so long because I was fighting internally. My gut feeling and my brain kept telling me certain things won’t work.”

But on the flipside, she also admits that a lot of synchronistic things started happening that affirmed she was on the right track. “I’d have this conversation, meet this person, be in this place,” Ntuli says.

It was all coming together.

A bit of this, a bit of that

Ntuli’s work speaks to myriad influences such as incorporating the flute, as is done in what is commonly referred to as spiritual jazz.

One album that remains top of her mind is Wandishi, American jazz pianist and composer Herbie Hancock’s 1971 release. But in 2016 she also attended a concert at Emperors Palace where greats such as Hugh Masekela were playing some of Abdullah Ibrahim’s compositions. The musicians’ use of flutes and trombones also piqued her interest, leaving her with the thought of playing around with those sounds, which she found meditative and soothing.

Hancock, now 78, has shared stages with greats including Miles Davis and is hailed as one of the pioneers who led jazz into the electric era.

In an interview he said: “I think it is up to musicians to encourage people to be courageous, to try things and listen to things they haven’t heard before. To hear things through other people’s ears … I like to discover new rules, so I can break them. I look around and see what is becoming a musical convention. And then I work out how I might break it. That’s where innovation comes from; that’s what keeps me playing.”

Exiled is a breaking. Of rules. Of convention. It is brave, experimental. It stands on the edge and isn’t afraid to look down. To leap.

It’s therefore perhaps not surprising that Ntuli has been named the 2018 Standard Bank Young Artist for jazz.

The next direction she will pursue may not yet be certain but it will certainly be contemplated, contemplative and adroit.