(John McCann/M&G)

The stronger dollar this week surprised the markets and raised the prospect of an imminent hiking of United States interest rates and concerns about the inevitable troubles this will create for emerging markets.

“It’s as though that has been a new thought. It’s as if people have just woken up to this,” said Stanlib chief economist Kevin Lings.

The rand reached its weakest level this year when it breached 12.80 to the dollar this week, before recovering. As Nedbank corporate investment bank analysts put it: “A stronger US dollar is a reflection of tighter global financial conditions, which is not conducive for risk assets [like the rand].”

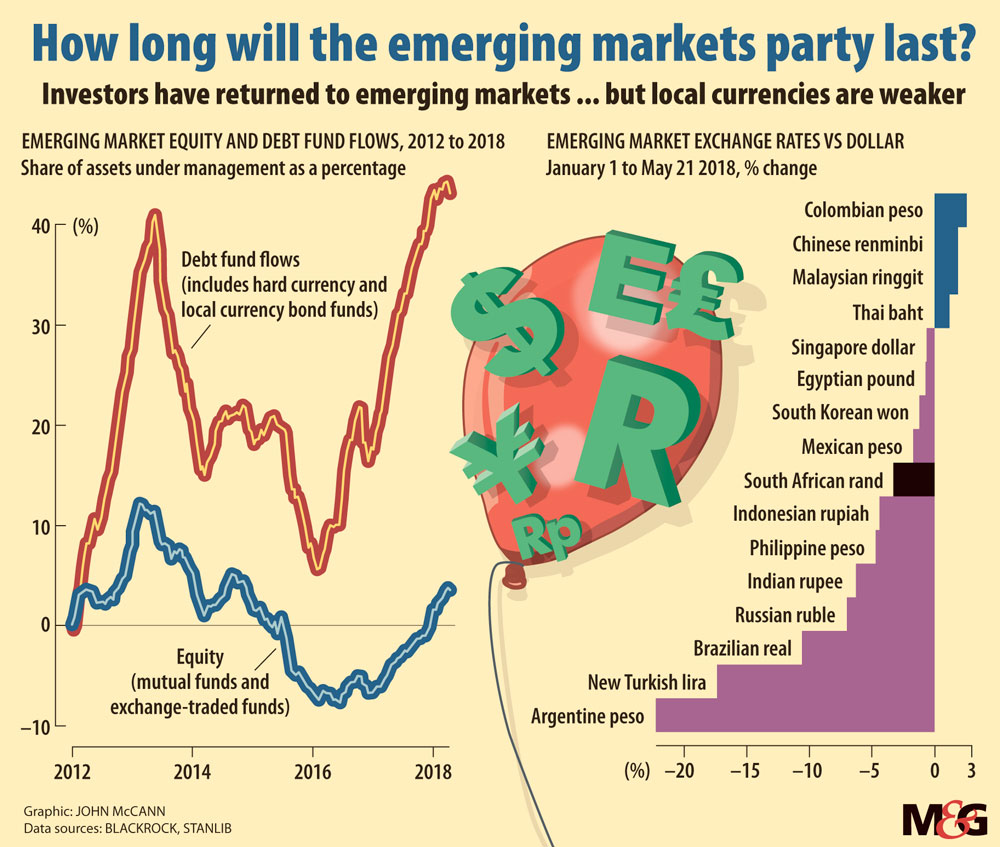

Richard Turnill, BlackRock’s global chief investment strategist, said in a note this week that emerging market currencies are down more than 3% in aggregate this year against the dollar, and emerging market equities have given up all their early 2018 gains.

Econometrix chief economist Azar Jammine said the dollar strength came as a surprise to most, especially in light of the US’s twin deficits — a budget deficit and a current account deficit.

Its current account deficit is $23-billion, compared with a German current account surplus of $310-billion or a Dutch surplus of $85-billion, Jammine said. “So the question people ask is: Why should the dollar strengthen against the euro, when those current accounts are in surplus?”

There is no clear reason. One factor may be that the imminent threat of a trade war between the US and China appears to have fizzled out. Another, Jammine said, might be new import tariffs for steel and aluminum imports is anticipated to push up inflation and possibly even spur on an interest rate hike.

The US Federal Reserve has been clear about its intention to continue hiking interest rates, said Lings. The interest rate differential and the relatively strong dollar, which could continue to strengthen, has attracted money to the US.

At the end of 2015, the Fed began a slow and steady rate-hiking cycle, increasing the rate from 0.25% to 1.75% currently. A few months later, the European Central Bank dropped the euro area interest rate to 0%.

Emerging markets have attracted $2.5-trillion in foreign portfolio investment over the past nine years, Lings said. The search for yield has even included frontier markets, which would normally have struggled to raise funds by issuing international bonds.

Both these markets have also attracted a great deal of crossover investors, who would not normally have ventured into these unknown territories but were attracted by higher yields.

“As the US raises interest rates, the money stops going to EMS [emerging markets], or even reverses. This has been accentuated by the fact that emerging markets are cutting rates, some of them quite aggressively,” Lings said.

Brazil has actively closed the gap between itself and the US, he said. It cut rates by 750 basis points, dropping them from 14% to 6.5% over 15 months. The South African Reserve Bank has cut interest rates by 150 basis points since last year, with the repo rate also currently at 6.5%, but the cut was not as aggressive, Lings said. Meanwhile, the Fed is under pressure to get interest rates up so that it will have room to cut.

“They need to do that because the US economy may well start to slow next year,” Lings said.

Different trajectories

The dollar’s strength has also encouraged investors to take a sharper look at the economic fundamentals of emerging economies, some of which are not in good shape. But Lings warned against a one-size-fits-all analysis of what is happening in emerging markets. “There are clear divergences across these countries and, more and more, that pattern will develop. Where you have countries that have a clear deterioration in economic fundamentals, they are being much more actively punished by the market now.”

South Africa is not one of these. Instead it falls into a camp where the market is unsure and, although there is some weakness, the economies are not tipping into positive or negative territory just yet, Lings said.

Then there are a few who break the mould. China has long been one. Another is Columbia, where a large oil industry benefits from the rising oil price, which recently briefly broke through the $80 a barrel threshold — a four-year high.

Focus on growth

Apart from yield, nations will now have to offer something else to investors — growth.

“In this world, which is nervous about interest rate differentials narrowing, there starts to be a search for growth, not yield. There will be a premium paid for growth in the world because growth is not easy to come by,” Lings said.

Some emerging markets, such as South Africa, have become investment destinations simply because their interest rates are substantially higher than in other markets, which is why the Reserve Bank has been nervous about closing the interest rate differential and what it would mean for the currency, he said.

South Africa has improved its economic fundamentals to some extent but “money is going to be harder to get hold of”, Lings said.

“It will be slow over maybe the next five years of so … but there is no doubt liquidity is going to dry up and investors will need to think more carefully. We will go back to an era where credit ratings and growth mattered more [than yield]. That’s the test for South Africa.”

Jammine said this bout of emerging market panic is not unlike what happened in 2015, although “the intensity is not quite as deep on this occasion”.

Then, the world economy was weaker and the downward pressure on emerging markets was more pronounced.

The concern was not just the strengthening of the dollar but also fears of a weakening Chinese economy. The US was also starting to scale back its quantitative easing programme, causing investors to buy the dollar.

“This time around there is no immediate fear of a major slowdown. The fear is more about that the US may hike rates faster than anticipated,” Jammine said.

But Turnill said, for emerging markets, the broader fundamentals are robust and he believed the drawdown in fact presents buying opportunities.

“We do not see a repeat of last year’s heady returns. But several trends underpinning the relative appeal of emerging market assets are intact,” he said, adding that BlackRock data points to the synchronised global expansion continuing in 2018.