Motala and Archbishop Emeritus Desmond Tutu listen to Nelson Mandela.

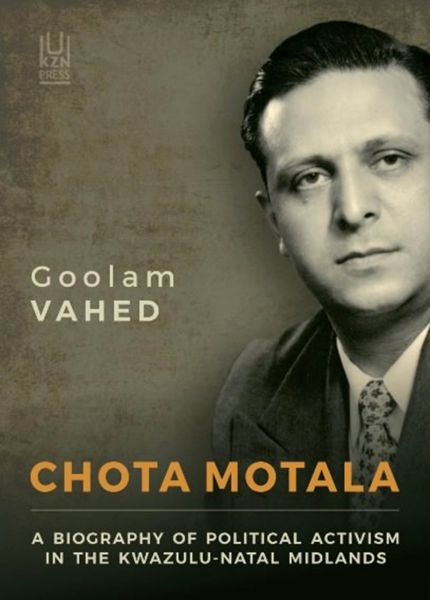

A recent book, Chota Motala: A Biography of Political Activism in the KwaZulu-Natal Midlands (KZN Press), recounts the doctor’s role in shaping politics during and after apartheid. This is an edited extract.

ACTIVISM

A sea change in the political climate took place from the mid-1970s, when student protests that broke out in Soweto on June 16 1976, ostensibly over the use of Afrikaans as a medium of instruction, rapidly spread countrywide. The protests were led by young people who … rejected an education system that prepared them to serve the white man’s farms and industries. Their determination to make their voices heard and refusal to be slaves in the land of their birth resulted in Dr Chota Motala describing this era as “a new spirit of revolt”.

As black South Africans gave vent to the years of anger that had been building up, the government employed the full force at its disposal to try to curb protest. Motala was involved in some of the high-profile political events around this time.

After his release from Robben Island in 1972, Harry Gwala started a laundry business in Pietermaritzburg with assistance from Motala and Vasu Chetty, who helped him to purchase a van. Gwala, however, was detained in December 1975 and accused with nine others of recruiting members for MK.

One of the accused, Joseph Mdluli, died in detention on March 19 1976. Phyllis Naidoo, defence attorney for some of the accused, recorded that Motala, Peter Brown, Vasu Chetty, Mavis Magubane and Elda Gwala “took care of the families of detainees in Pietermaritzburg” by providing accommodation, meals, medical treatment and other logistical support as it was required. Naidoo referred to Motala’s medical practice as “the subversive surgery”.

An increasingly desperate government, faced with burning townships and international censure after the Soweto uprising, cracked down severely on all activism. Meetings were banned and activists harried, beaten up, banned or detained. A number of activists died in police detention. In the wider Pietermaritzburg area, Pan Africanist Congress member Samuel Malinga died at Edendale Hospital on January 31 1977 after being detained for 22 days and Aaron Khoza, also a PAC member, was found dead in his cell on March 26 1977 at the Old Prison in Pietermaritzburg.

A third death connected to Pietermaritzburg was that of Hoosen Mia Haffejee, whom Motala knew because he grew up in the city. Haffejee had matriculated from Woodlands High in 1966, qualified as a dentist in Nagpur, India, in 1976 and obtained an internship at King George V Hospital in Durban. He was arrested under the Terrorism Act on August 2 1977 and taken to Brighton Beach police station in south Durban where he was interrogated for several hours and put into a police cell shortly after midnight. He was found dead the following morning in suspicious circumstances.

[Ismail Haffejee and Sarah Lall (left) with a portrait of their brother Hoosen Mia Haffejee, who died in police custody in 1977. (Rogan Ward/M&G)]

An inquest in March 1978 into Haffejee’s death was presided over by magistrate TL Blunden. It was not atypical for deaths in detention that underwent investigation, the state giving itself leave to produce patent fabrications for causes of death. Dr W Cooper, Harry Pitman and Ismail Mahomed represented the Haffejee family. Motala helped Ismail Mahomed, future chief justice of South Africa, to prepare for the case. Professor I Gordon, the chief state pathologist, concluded that, notwithstanding police beatings, death was caused by hanging. Blunden’s official verdict absolved the police of any homicidal action.

A frustrated Motala recorded in his notebook: “In 1977 a young Pietermaritzburg doctor, Dr Hoosen Haffejee, was arrested by the security police in Durban and died in detention 12 hours later. We were determined to challenge the cause of death and together with Dr David Biggs, a leading orthopaedic surgeon, we provided detailed evidence to the inquest that there were numerous injuries on Dr Haffejee’s body which remained unexplained. Needless to say, as with the Biko hearing, no one was found to blame by the inquest. As a medical professional and a political activist I tried at all times to ensure that the community of health professionals were made aware of the numerous problems which arose from the practice of apartheid and the violence perpetrated by police officers on their detainees.”

READ MORE: Luthuli inquest could be reopened

Hoosen’s brother Yusuf Haffejee was repelled by Gordon’s findings. He told the post-apartheid Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC) that the inquest “served only one purpose . . . to exonerate the Security Police”.

He spoke of the help that he received from the local community: “I contacted my school mate, Attorney Morgan Naidoo … and asked him to please come down to Durban. He came with advocate Harry Pitman and Dr Motala. We had a discussion, and as a result of that, advocate Pitman tried to get the services of a pathologist. He failed. Then he tried to get the services of any medical specialist, and didn’t succeed there either. It became clear to us that most specialists, members of a very noble profession, had no intention of tangling with the Security Police. Morally reprehensible conduct comes in all colours. Eventually Dr David Biggs, an orthopaedic surgeon, fearlessly rallied to our assistance. Helped by Dr Motala he conducted an examination and he took down notes … We remember the late Dr David Biggs, a quiet and unassuming person, for his bravery in the face of fascism, and Dr Motala for coming immediately when we needed his help.”

The TRC commissioners found that the police made “routine use of assault and severe torture as part of a systematic campaign to silence and suppress opponents of the South African government. The acts of severe ill treatment perpetrated by members of the South African Police (SAP) constitute gross violations of human rights. In some instances, these unlawful acts resulted in the deaths of detainees. The SAP is held accountable for these gross violations of human rights.”

READ MORE: Apartheid killings and awkward questions

Despite these conclusive words, deaths in detention appear to have had few consequences for perpetrators, but they did have wide ramifications for the organisation of health professionals in South Africa. While the medical and security establishments brushed aside the death of Haffejee, the death in detention of Black Consciousness Movement leader Steve Biko on September 12 1977 created an international storm that had implications for the local medical profession. Motala had maintained that his political activism would be meaningless if it did not carry over into his medical work and vice versa. He was appalled by the rulings in the cases of Haffejee and Biko.

The South African Medical and Dental Council (SAMDC) resolved not to take any action against the doctors for what appeared to be blatant negligence. The SAMDC’s decision was supported by the Medical Association of South Africa (Masa).

The SAMDC’s and Masa’s collusion with the apartheid regime resulted in black doctors charting a separate course. Fifty-two healthcare professionals in South Africa, including Motala, launched the National Medical and Dental Association (Namda) on December 5 1982. The immediate impetus was the outcome of the inquest into Biko’s death, but more broadly it was inspired by the effect of detention without trial on prisoners and inequitable apartheid health care provision.

Namda constituted a noble part of the civic groups mobilising in the country to dismantle apartheid; and it supported various sociopolitical campaigns and economic, cultural, academic and sporting sanctions against South Africa. It is plain that the liberation movement was reliant across multiple spheres of public life on professionals such as Motala involved in the founding of Namda, who were socially committed and politically conscientised.