Mighty memes: By deconstructing the notion of art

We take art as it is and make of it what we want. The artist has the responsibility to take their labour and bring it to life for their audience. We live in an information-driven age, in which our digital calendars ping to remind us of where the next cool gig is for a night out with friends.

On Thursday morning I received an email with a shortened URL link and a brief description about an internet project — and then later, a Twitter notification with a photo tag pops up from Tiger Maremela (aka A VERY COOL TIME), about their first solo exhibition at the J&B Hive in Braamfontein. We retweet with much excitement. The internet is an interesting place to live.

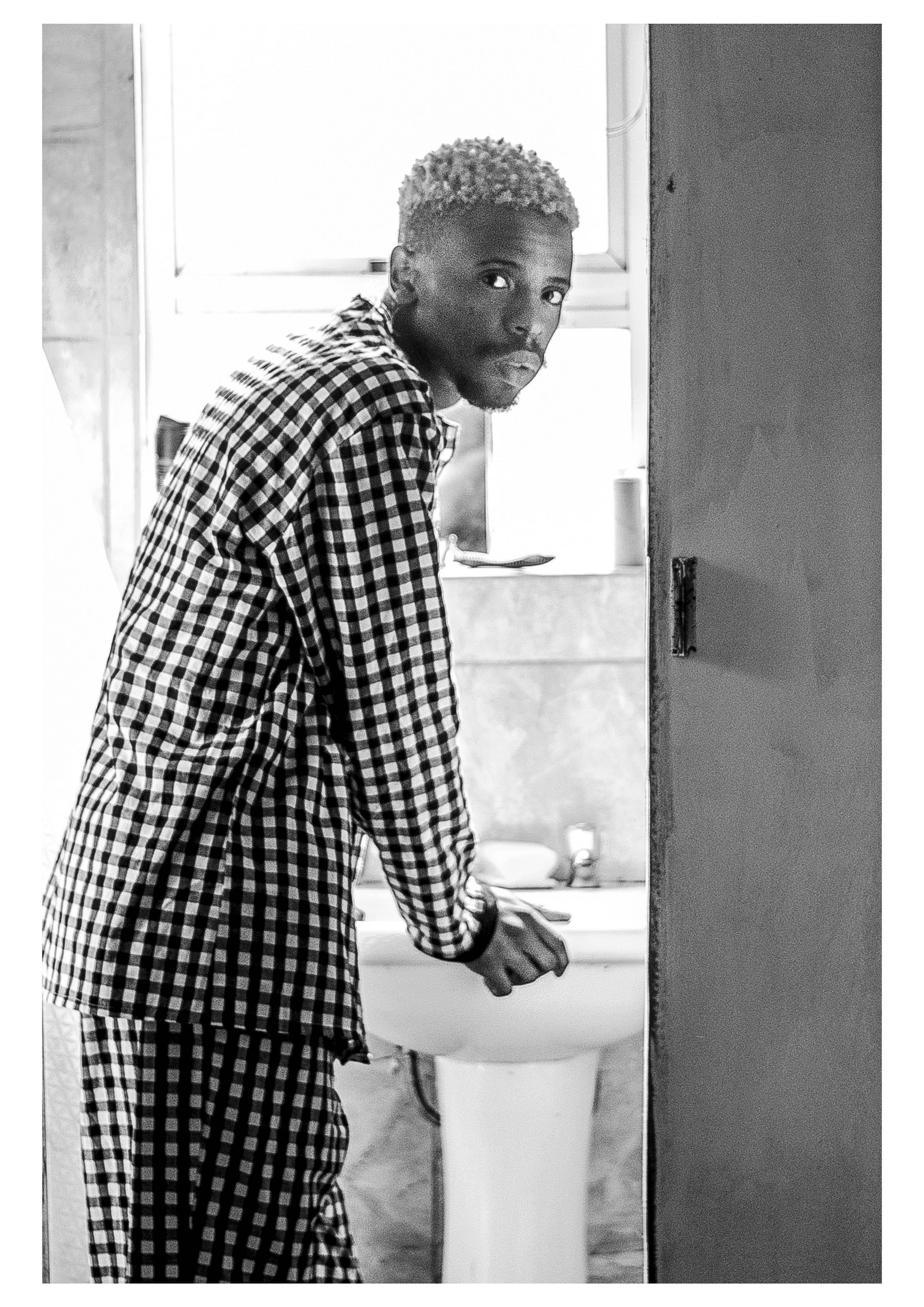

Maremela is a Johannesburg-based, nonbinary internet artist trying to make sense of the world by endlessly scrolling through the worldwide web. Their work ranges from photography, video, writing, music and collage-making, where they locate source material from their own experiences. The artist is interested in the centring of black, queer and trans South African voices in the imagination of the post-apartheid state.

By exploring the often binary approaches to sexuality, gender identity, class, race, ability and the ways in which power intersect, the artist seeks to reimagine the realities of black, queer and trans youth in South Africa.

Maremela’s work is called Where Some Things Are Beautiful & Everything Hurts, found by a click on a URL that takes you to a one-page website filled with 1:1 collages and a description of the project.

Fun fact: the site was put up overnight before it was released to everyone, which says something about Maremela’s connection to the DIY, rapid-fire rhythm of the web. Clicking on the images takes you to other internet platforms where you can consume various forms of media: Vimeo, SoundCloud, Twitter, Tumblr, Facebook, a short magazine with images and a series of texts from the artist on the online platform Issuu, and a link inviting you to send the artist an email.

They’ve used these various links and platforms to display their art, bending and playing with them as tools of information and networked communication from our phones and computers. Maremela has created an artwork that draws the audience into the rabbit hole of the internet — a place where you can get lost — listening, gazing, reading and taking part, radically reshifting the one-dimensionality of contemporary art.

This form of digital art should come as no surprise, because some artists are moving away from the fine art hung in art galleries and opting for a far more rich media platform that is accessible to anyone at any time.

I’m reminded of French art critic and curator Nicolas Bourriaud’s theory of relational aesthetics when I view Maremela’s work. The term “relational aesthetics” or “relational art” was coined in 1996, which, simply put, is a set of artistic practices that erases the line that separates audience from art.

The theory makes use of social events, which can include anything, such as making soup in a kitchen to reading a book.

In Maremela’s case, attending the Soundscapes of a Warzone exhibition and browsing the internet is a social experiment. The whole concept depends on the artist’s ability to recreate a “real” environment for the spectator, akin to the one we experience daily.

Maremela’s browser-based project invites the audience to participate in the dialogue of whether black, queer and trans youth are able to take up space and go about making space for others. Included in the project are three EPs of ambient noise, which were played at the exhibition. Listening to them in real time, I felt as if I was entering a space that sounded like a war zone. The sounds from the three experimental tapes, namely, Justice, Prince Moroka/Browser History and Future Soundscapes for Past Tense Traumas were equally disturbing, immersive, overwhelming and bizarre.

“The EPs were made from my phone and GarageBand, which is, like, an entry-level music software. It varied,” says Maremela.

Even when they explain their process, Maremela’s language is peppered with the playfulness of a #relatable tweet. “It took, like, two hours or two months to complete a song. Justice and Prince Moroka were the hardest to make, because I was going for a very specific sound, but they were the ones I was satisfied with the quickest. Future Soundscapes was emotionally draining [insert crying emoji].”

Maremela drew their inspiration from multiple sources: from ballroom music made popular by black, queer Americans, industrial motifs, global protests and even ideas of what space itself sounds like. The exhibition invited the listener on a musical journey that delved through the artist’s childhood trauma, teenage infatuation, existential angst and political tension. The commentary created using news clips, field recordings of everyday household fixtures and the sounds of animals going about their daily lives resulted in layered, explorative dreamscapes that attempt to reveal the listener’s bias and subjectivity.

I’m reminded of Vanessa Beecroft’s conceptual work, for which the Italian performance artist used live models on a large scale, many of whom were nude, to create an existential encounter between the models and the audience. Like Maremela, Beecroft made sure that documentation took place at the exhibition, via using video recording; critics described her work as “brilliant, disturbing and provocative”.

At the J&B Hive, Maremela’s multidimensional internet pieces covered the walls. Photographs from Coverpersons — which showed the artist in different personas from their #BraamBae series — surrounded us, as wells as excerpts from Falling in Love with Priests, the artist’s debut chapbook, which contemplates young love, heartbreak, sexuality and religion.

Maremela also turned the lens on themself, in a number of self-portrait series called dituku/dinaledi, Coverpersons and Watching you watch me. In dituku/dinaledi the artist confronts questions of intergenerational dialogue and self-acceptance, and Coverpersons reimagines early South African gay magazines. Watching You Watch Me explores the ideas surrounding selfie culture, and plays with aspects of the viewers’ gaze and the extent of subversion.

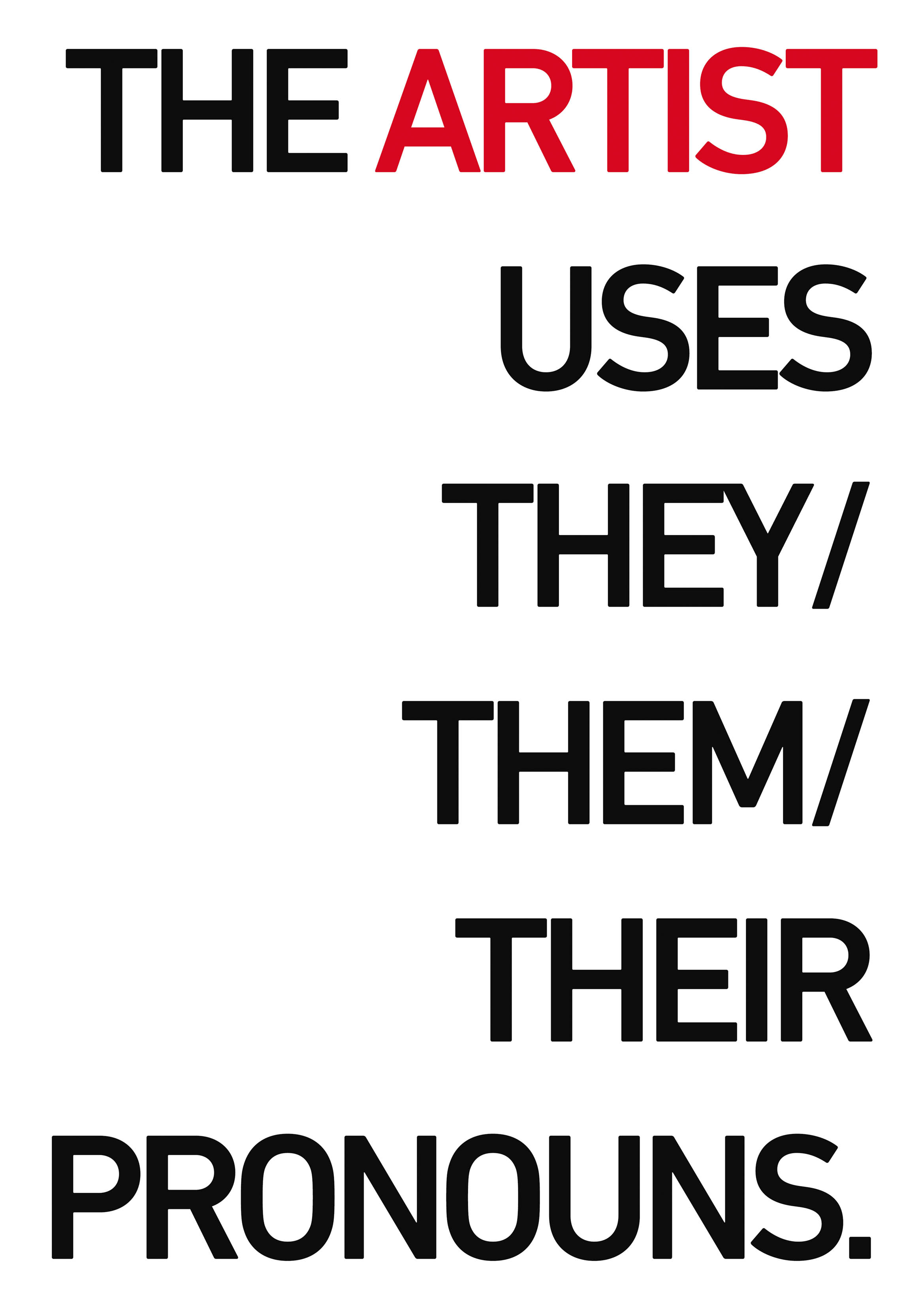

Some of the prints on the wall at the exhibition made declarative statements such as: “The artist uses they/them/their pronouns” and “memes are the only things keeping me alive right now”. Considering that meme culture was made popular by music stans (overzealous fans) on Twitter, for which queer people were often the creators, it all starts to make sense. For queer creators, memes are the poetry of survival.

We see this dynamic clearly in Maremela’s work, in which a click on a collage also takes you to the artist’s writing, which ranges from poetry to personal essays and a series of newsletters. Maremela works through experiences of online vulnerability, religious and sexual frustration, unrequited love, hope and possibility.

Internet Treatz, a series of newsletters written by Maremela and shared with a community of subscribers from 2016 to 2017, is an invitation into the artist’s browser history and heart. This is not a coming-out story; it is a short essay detailing the artist’s transition to a nonbinary individual from 2015 to 2018. Also included is Cryingintheclub, a photographic essay of Jo’burg’s queer and trans community inside club spaces they’re reclaiming.

The breadth of Maremela’s art could also be viewed as a nod to Rirkrit Tiravanija, a Thai contemporary artist from the 1990s who pioneered relational aesthetics in his work. Tiravanija would create installations to which the public could come and make food in his kitchen and take breaks in his lounge. He would also leave Thai soup at a collector’s home, which served as dinner and as an artwork.

By deconstructing the concept of art into its basic components, the artist focused on the interactions between people and their surroundings, rather than aesthetic objects. Maramela’s work does the same, by allowing the internet user to browse and engage with their art in the form of photography while listening to the EPs or watching the videos found within the URL.

Maremela’s work is a stunning tribute to the interconnectedness of things, and the various networks, digital and otherwise, that tie us to each other. Their work is a reminder of how important it is — now, more than ever — to connect with and engage in black queer art. By doing this, we bring value to our realm, while amplifying and validating that community’s existence.