Nigeria’s players prepare for the game against Iceland in Volgograd

Abuja — When the new Nigerian football shirt was released in June, just a few weeks before the Super Eagles departed for Russia, it became an instant classic.

“It’s very unlikely that Nigeria’s taking home the World Cup this year. Very, very unlikely. But at least they’ll take home one title — and that’s the tournament’s best kit,” according to the magazine Esquire.

From Lagos to London, there were long queues as football fans competed with hipsters to get their hands on this summer’s hottest fashion statement. Online, Nike received a staggering three million orders, smashing existing sales records. And although the kit made only one World Cup appearance, in the 2-0 victory over Iceland, demand remains high.

It’s not hard to see why. The jagged, dazzling green and white zig-zags are utterly unique but also immediately familiar to anyone who has ever seen the tessellated Ankara fabrics that are so popular in Nigeria.

The shirt is, according football writer Indro Pajaro’s breathless prose, a “hymn to streetwear fashion”, “an electric fantasy” in green, white and black that “seems to explore futurist universes while remaining faithful to the tradition and pride of Nigerian traditional colours”.

If Wakanda had a football team, this is the kit they would wear.

It’s cool. And I want one.

Searching for shirts

I looked everywhere. Nothing in the Nike store in Johannesburg. Sold out in London. Getting desperate, I even visited the Nike store in an exclusive mall in Abuja, Nigeria’s capital city, where the only replica jersey I saw was being worn by the shop assistant. He laughed when I asked him if he had any more in stock. “They disappeared as soon as they came in,” he said. “Nike only gave us very a little quantity.”

Despite this apparent dearth of supply, I saw Nigerians all over Abuja sporting the new design. They are hard to miss: young men swaggering down the capital’s wide streets, teenage boys kicking a ball around in a dusty car park. Where did they buy it? I stopped someone and asked. “Go to Wuse market,” he said.

Wuse is Abuja’s largest market. There is not a lot this place doesn’t sell. Pyramids of tomatoes; baskets of cabbages and plantains by the bunch; plastic buckets in every shape and colour; boxes of expired fruit juice imported from the Arabian Gulf; lengths of local fabrics; electronics with unrecognisable brand names; stainless steel pots and pans.

It’s all here — including a fine collection of fake football shirts.

Manchester United is popular, and Barcelona. There are a few Real Madrids, some Chelseas. And there, in pride of place, the black, green and white of the new Nigerian home kit.

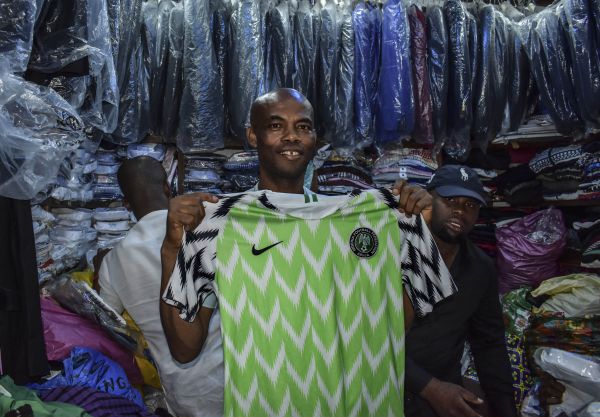

After some negotiation, I buy a replica shirt from Sir White, the manager and owner of St Stevens Collections Ltd, which sells menswear in a tiny stall in the clothing section of Wuse market.

Going native: Sir White (above) sells counterfeit Nigerian football shirts that his brother sends him from Guangzhou, China, as part of a nationwide trade in imitations that Nigerians can afford. By contrast, the Nike store in Abuja (below) sold originals for more than twice the monthly minimum wage. (Simon Allison/M&G)

Sir White grew up in Anambra State in Nigeria’s southeast. He is from the same village as Chief Chukwuemeka Odumegwu-Ojukwu, he proudly tells me, the first and only president of the ill-fated Republic of Biafra (Biafra is the country that seceded from Nigeria for three years between 1967 and 1970, only to be crushed by Nigeria’s army in a brutal war).

In his youth, a good 30 years ago, Sir White was a semi-professional football player in Lagos. He was good at it too. “I played number nine. I scored lots of goals.”

But a torn ligament ended his sporting career and he turned to trading. It was a natural transition — people from his part of the country are famous for their business acumen, he said.

Instead of wearing football shirts, he now sells them. He also sells suits, blazers, collared shirts, polo shirts, T-shirts and various styles of traditional Nigerian men’s outfits — native clothes, he calls these. He doesn’t sell as many football shirts as he used to, or as many suits, because his customers are preferring the traditional styles.

“Now Nigerians wear native. It started with the former president, Goodluck Jonathan, he is the one who started to make people wear native. Now the new president and his deputy are also wearing native, so the business is more for native clothes.”

All of his stock, including the football shirts, comes from China. Sir White’s brother lives in probably the global capital of informal trade, Guangzhou. There is a whole colony of African traders who now live in the city, sourcing fabrics and cheap goods and finding inventive ways to export stuff home.

I have previously reported on similar markets in neighbouring Hong Kong. It’s a stressful life. Traders often live in squalid conditions and operate on razor-thin profit margins, and things are made worse by the routine racism many experience. One Guangzhou neighbourhood with a large African contingent has been given the derogatory nickname “Chocolate City”.

Sir White phones his brother and tells him what customers want. The brother boxes the goods and puts them in the cargo hold of a plane bound for Abuja, where Sir White is waiting to collect them. With all the hype surrounding the new Nigerian football shirt, Sir White put in a special order. “When I collected them from the airport, I paid all the duties,” he said. “This is not contraband.”

The 8 000 naira price tag (R300) — a fifth of the price charged by Nike — somewhat undermines this assertion. So too does the fact that of the three shirts I examine closely, each is a slightly different shade of green.

Nigerian fans prepare for the game against Iceland in Volgograd, Russia in June. Their national football shirt smashed existing sales records. (Catherine Ivill/Getty Images)

Nonetheless, the word “authentic”, along with a serial number, has been sewn on to each shirt in a small black rectangle.

“So where does your brother get his football shirts?” I asked Sir White. He said he doesn’t know. But I have a few ideas.

My life of crime

A confession. In my youth — long enough ago for the statute of limitations to expire, I hope — I was a smuggler of fake football shirts.

Part of my family lives in Thailand and I travelled there regularly. When I returned to my small university town in South Africa, my suitcase would be laden with replica kits, often wrapped up as Christmas presents to evade suspicion. We’re not talking a huge number — maybe two or three dozen shirts per trip — but more than enough to keep a struggling student in beer money.

I would advertise on the noticeboard of my university residence, selling for twice what I paid, but half of what a real one would cost in the shop. As ever, Manchester United was most popular.

Over the course of several trips, I learnt a few things about the fake football shirt trade.

My contact in Thailand ran a sports equipment shop, which was really just a front for a much bigger factory that his family operated in Bangkok. No one came to the shop for the badminton racquets or the cheap trainers he sold, some of which had been on display for years. They came to order football shirts, sometimes individually, sometimes in bulk.

It was very much a family business. My contact had two brothers working in China, one in a Nike factory and one in an Adidas factory. As soon as these factories began to produce the latest designs, the brothers would steal the blueprints and send them to their own factory in Thailand.

Nigeria fan strikes a pose in Ankara garb at Sheremetyevo Airport in Moscow, Russia. (Ryan Pierse/Getty Images)

The factory made fakes in three grades. The cheapest grade looked fake: you could tell from the shiny, plasticky material, and the missing manufacturers’ logos. The middle grade looked exactly right, but was made of relatively cheap nylon material that didn’t breathe at all when you wore it. Play actual football in it and you end up a sweaty mess.

Shirts in the most expensive grade were objects of great precision. They were accurate in their measurements to the nearest millimetre, used high-tech sports fabric that mimicked the texture of the original, and came complete with all necessary tags and labels. “This is an authentic Nike product,” the tags proclaimed, and no customer was ever going to tell the difference. Certainly not the customers that bought from me. Or those who buy from Sir White, whose Nigeria kits would have travelled along a very similar supply chain.

Counterfeit is king

I never felt guilty about smuggling fake football shirts. It seemed like a victimless crime. Real football shirts are inexcusably expensive, and it’s not like the big sportswear giants are struggling for profits.

But perhaps my conscience should have troubled me. For several years, I was part of an illicit, informal global counterfeit economy, in which football shirts play a relatively minor role. But other products are faked too — with far more dangerous consequences.

Nowhere is this more obvious than in Nigeria’s bustling markets, where it can be hard to tell if branded goods are fake or real. There have been many cases of fake toothpastes, fake baby formula, and, recently, even fake fire-fighting equipment. The implications for health and safety are obvious.

According to an estimate in Nigeria’s Nation newspaper, a staggering 80% of products in the economy are either fake or substandard.

Over the past year, the Standards Organisation of Nigeria has confiscated more than 6.5-billion naira worth of fake tyres; and earlier this month, the National Agency

for Food and Drug Administration and Control destroyed fake tramadol and other pills worth 3.5-billion naira.

“The counterfeiting of many different products is on the rise globally and in Nigeria today items counterfeited include documents, currency, software and electronics, among many others. However, no other product has as much capacity to kill consumers as illicit pharmaceuticals,” wrote Angela Adebayo, a Lagos-based patent attorney, in an article last year.

In the illicit nature of the trade, it is hard to estimate the prevalence of informal drugs in Nigeria’s health system, but every now and then a major tragedy reminds us that the difference between fake and real can be the difference between life and death. In 2008, for example, 34 Nigerian children died and 50 were hospitalised after taking adulterated paracetamol.

The flip-side, of course, is that counterfeit goods — when they are not fake pills or fake fire extinguishers or anything else life-threatening — allow Nigerians access to products that most could never possibly afford otherwise. Products like Nigeria’s own national football shirt, which officially retailed for 41 000 naira for the few hours it was available. That’s the more than twice the monthly minimum wage.

For better and worse, this is a country where counterfeit is king. In a sense, the knock-off version of the Nigerian kit may be a more authentic expression of national identity than the real thing.

Just ask the shop assistant in the Nike store in Abuja. Surrounded by racks of authentic high-end sportswear, he gestured towards his own replica Nigeria shirt. “This one,” he said, tapping his chest. “It’s a fake.”