President Recep Tayyip Erdogan is at the core of Turkeys economic woes. (Murat Kaynak/Anadolu Agency)

If you had to look at South Africa’s total trade —imports and exports — as an indicator of how important Turkey is in the economic scheme of things, you’d see that, at just 0.5% of our total trade for the first six months of this year, it is hardly worth mentioning.

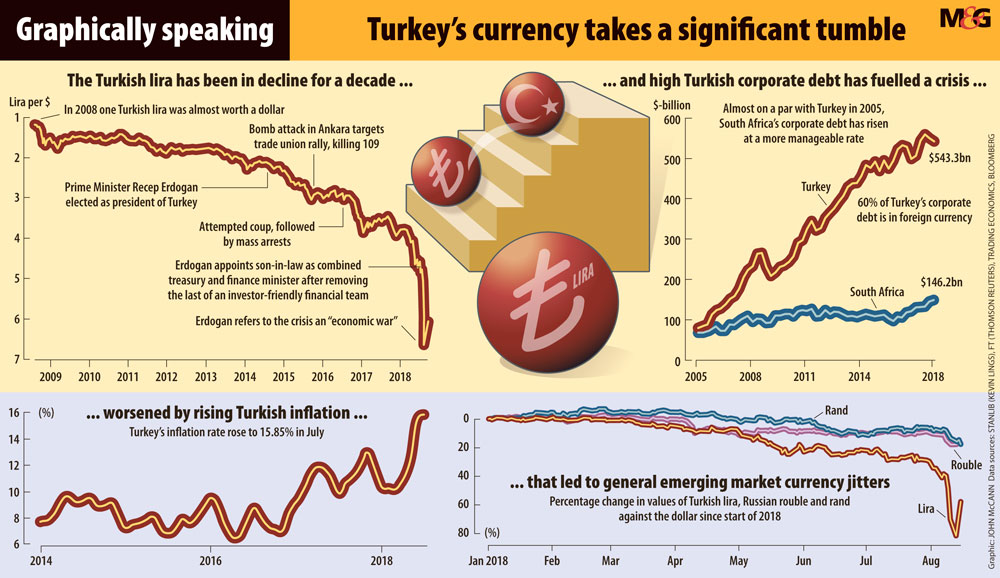

Yet there was the rand being smacked to R15.41 in the early hours of Monday morning when most rand traders were fast asleep. When normal market trading resumed the rand recovered somewhat to R14.77. But in the big sell-off of the Turkish lira that followed on Monday, so-called emerging-market contagion saw the rand sold too.

As if President Cyril Ramaphosa doesn’t have enough post-Zuma economic problems as it is, somehow we are now embroiled in Turkey’s troubles as well.

The Turkish economy has significant problems on multiple levels, says Stanlib economist Kevin Lings.

“These include poor political governance, especially after the failed coup attempt in July 2016, a large and growing current account deficit that averaged -5.5% of GDP [gross domestic product] in 2017, and was projected to rise to around -6% of GDP in 2018, and an annual inflation rate that is already over 15%, which is more than three times the inflation target and [is] likely to rise significantly further, given the recent currency depreciation.”

Lings also notes that the 10-year government bond yield has now increased to more than 21%, the central bank repo rate was recently pushed up to 17% and a currency that has declined by more than 45% against the US dollar since the beginning of 2018 has weakened by 28% in the past week.

If all this was not enough, regional strongman Recep Tayyip Erdogan finds himself embroiled in a fight with the superpower strongman Donald Trump, who has been roaming the globe looking to pick fights wherever he can,with one notable exception —the muscular Vladimir Putin.

The row is about the charges faced by a United States pastor, Andrew Brunson, who is alleged by the Turkish authorities to have supported Fethullah Gulen, an exile who lives in the US and is accused by Erdogan of masterminding the unsuccessful coup attempt in 2016. Brunson faces terrorism charges in Turkey.

He is important to Trump, commentators say, because he is seen as a martyr in the eyes of the US Christian right. With elections looming, Trump wants Brunson released as a vote catcher for his base.

Trump this week announced the doubling of tariffs on Turkish steel and aluminium, starting a tit-for-tat. Erdogan responded with tariffs of 120% on US cars and 140% on alcoholic drinks. He also called for a boycott of Apple products in favour of Samsung, and a general ban on importing electronic goods from the US.

Trump ordered that F-35 fighter jets destined for Turkey, a Nato ally to the US, should not be delivered.

The real difficulty Turkey faces is deeper than these tit-for-tats, though, and results from the changing financial landscape, in which cheap money made possible by the ambitious monetary easing programmes of the major central banks are now being rolled back. Interest rates are increasing as the era of cheap money ends.

Turkey, which under Erdogan has pursued a programme of building mega projects using foreign money, now finds that the costs of debt service have been rising. This has been exacerbated by a nose-diving lira.

Lings says:“It is the level of corporate debt that may inflict the most amount of damage over the coming months. Since the first quarter of 2005, Turkey’s corporate debt has risen from $78.9-billion to a staggering $543.3-billion in the first quarter of 2018. That represents an average annual increase of 16%.

“Furthermore, almost 60% of Turkey’s corporate debt is in foreign currency (mostly euros and dollars), which has become significantly more onerous given the recent currency weakness. This has raised concerns about debt restructuring, or possible default.”

Analysts are unanimous about what is at the core of Turkey’s economic distress, and that is Erdogan himself, who has imposed himself on much of Turkish life, including monetary policy, with which he led anattack on the independence of the central bank.

In May, in an interview with Bloomberg TV, Erdogan explained why he wanted more control over the central bank and interest-rate policy, The New York Times reported.

“When the people fall into difficulties because of monetary policies, who are they going to hold accountable?” he asked. “Since they’ll ask the president about it, we have to give off the image of a president who is influential on monetary policies.”

His stranglehold on the economy has not been helped by his appointment last month of his son-in-law, Berat Albayrak, to head both the treasury and the finance ministry.

The central bank has hiked rates by five percentage points since April, but this is seen as too little too late to rein in runaway inflation. The options now available are drastic and could bring hardship and at least a degree of humiliation. They include imposing capital controls, hiking rates probably by at least another five percentage points and perhaps being forced into an International Monetary Fund programme.

By week end, though, Qatar emerged to offer relief to the embattled Erdogan, stumping up $15-billion, which it said it would make in investments.

The end of easy money from the major central banks has meant a swing in sentiment away from emerging markets, as investors pursue less risky returns in developed markets. The turmoil in Turkey is both a manifestation and an escalation in the process.

South Africa is caught up in the Turkish turmoil because emerging economies are at greater risk in an environment of more pricey money. Additionally, South Africa is in this net because the rand is a highly traded currency;it is easy to buy and sell. For this reason it is traded not only by people who want to buy and sell rands but also by those who want to use it as a proxy for other emerging currencies.

South African government debt at 50% of GDP is probably as high as it can safely go, but most of this is issued domestically,meaning that it is paid in rands, not dollars. The country’s corporate borrowing, as Lings points out, is low, having increased from $65.1-billion to $146.2-billion between 2005 and 2018, an annual average increase of only 6.4%.

Ramaphosa has enough problems of his own as he tries to undo the damage of the Zuma wrecking ball and introduce expropriation without compensation in an economy that needs to be taken off life support and make its own way in the world.

With Syria on its border and all the dislocation this means, Erdogan’s is a tough neighbourhood. Istanbul may be a continent away from Pretoria but Ramaphosa now finds himself in the same hot locale.