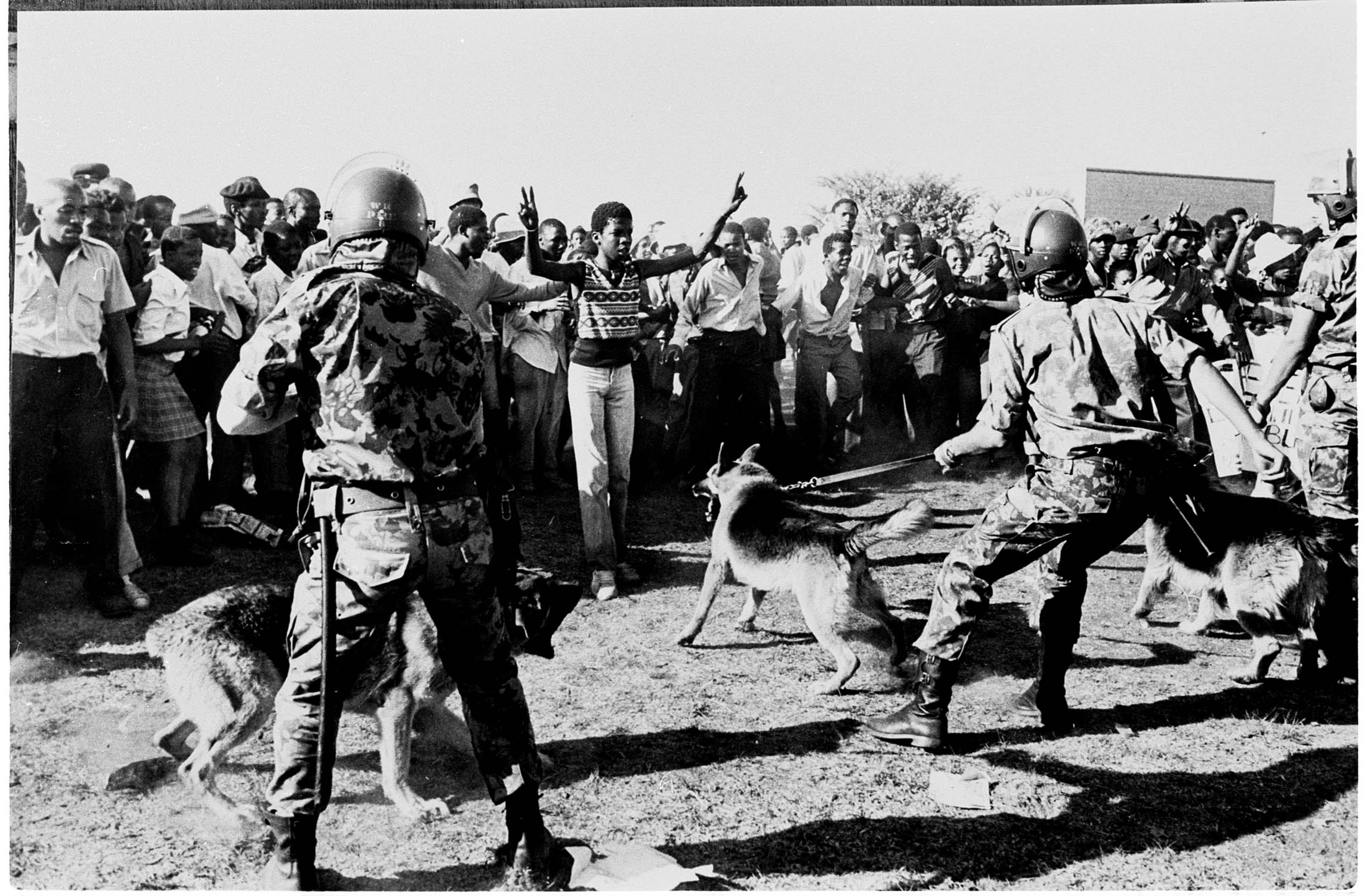

South Africans used the tools of civil disobedience and mass action to fight their oppression.(UWC Robben Island Mayibuye Archives)

Institutionalised race discrimination was the hallmark of apartheid. The legal order constituting apartheid provided for unequal separation and discrimination in the allocation of basic human rights.

Law was buttressed by convention and by a perception that the requirements of the law reached further than they did. Race discrimination was prescribed by law and enforced by law. Statutes, regulations and judicial decisions commanded and authorised race discrimination in almost every sphere of life. Signs in public buildings, parks and beaches indicated clearly the racial group allowed to use each amenity.

All features of the apartheid legal order were obscene but the Group Areas Act and the pass laws, with which I had most experience in my professional life, were among the worst. I was working with a community organisation, Actstop, established to oppose these prosecutions and evictions. Working closely with the Centre for Applied Legal Studies and Lawyers for Human Rights (LHR), it compiled a roster of lawyers willing to act free of charge to oppose prosecutions.

The lawyers who volunteered their services to Actstop were free to raise any defence that they believed might halt the prosecutions. Jules Browde SC, president of the LHR, raised the defence of necessity, arguing that those prosecuted had nowhere else to live, as the coloured and Indian areas were completely overcrowded. Although this argument received a sympathetic hearing, it was dismissed.

When I came to defend a coloured family charged with illegal occupation — that of Ivan Werner, his wife and young child — I pondered about the defence to raise. The night before I was due to appear in court, it suddenly occurred to me that I might challenge the validity of the government proclamation zoning central Johannesburg for exclusive white occupation on the grounds of unreasonableness.

Although the validity of laws enacted by Parliament might not be questioned by courts, the validity of proclamations enacted in terms of such laws — known as subordinate or delegated legislation — might be challenged on grounds of unreasonableness. Moreover, there was authority for the proposition that subordinate legislation that discriminated unfairly on grounds of race was unreasonable unless clearly authorised by the enabling Act of Parliament.

My only difficulty — a major difficulty — was that this argument had previously been raised in respect of the Group Areas Act and rejected by the Appeal Court in the notorious case of Lockhat vs Minister of the Interior on the grounds that the Act authorised racial discrimination.

In this case, the court held that the Group Areas Act was “a colossal social experiment” involving the large-scale movement of people throughout the country. “Parliament must have envisaged,” said the court, that it would “cause disruption and, within the foreseeable future, substantial inequalities.” The court added, in the manner of Pontius Pilate, that it was not for it to decide whether this would “prove to be for the common weal”.

Decisions of the Appeal Court are not absolutely binding and might be challenged, even if this was very seldom done and most lawyers believed that it was irresponsible to do this. On the other hand, even if my argument failed — as was most probable — it would secure a suspension of all prosecutions pending the decision of the Appeal Court, which would take at least two years. This was because no prosecutions could be brought while the law was being challenged.

During this time prosecutions might be overtaken by political events relating to the government’s determination to provide political rights to coloureds and Indians.

Elated by these thoughts, I went to the magistrate’s court the next day and informed the magistrate that I was challenging the validity of the proclamation zoning Johannesburg “white” under which my clients were prosecuted. The magistrate was surprised but accepted that in law he had no alternative but to postpone hearing pending a decision of the Supreme Court, which alone could consider such challenges to the validity of a proclamation.

Determined to have the matter argued by an experienced senior counsel, I asked Ernie Wentzel, a prominent human rights lawyer, if he would lead me. Ernie agreed, but the Johannesburg Bar Council ruled that he might not appear with me because, although I had been admitted to the Bar, I was not a member of the Society of Advocates.

I was appalled by this invocation of a trade union rule in a matter of public interest, involving human rights, in which lawyers would appear free of charge.

The author recalls in his book how he also used legal instruments to frustrate the aims of apartheid legislation during his career as a lawyer. (UWC Robben Island Mayibuye Archives)

The author recalls in his book how he also used legal instruments to frustrate the aims of apartheid legislation during his career as a lawyer. (UWC Robben Island Mayibuye Archives)

The decision of the Johannesburg Bar Council left me no option but to argue the case myself, with the assistance of Jonathan Burchell, a senior lecturer at the University of the Witwatersrand and an expert in criminal law, and Shun Chetty, one of the leading anti-apartheid attorneys, who had also volunteered his services to Actstop.

It was no easy task to challenge the validity of a proclamation on the grounds that it discriminated on the basis of race.

In order to do this, it was necessary to obtain evidence of discrimination not only in housing but also in respect of health, education, family life and delinquency, which were a necessary consequence of the zoning of separate group areas. This meant examining documents, speaking to experts in these fields, and persuading witnesses to testify to the discriminatory consequences of separate group areas. The hearing of the challenge to the proclamation took place in Johannesburg in the Witwatersrand Local Division of the Supreme Court.

In essence we produced for the first time in South Africa what is known in the United States as a “Brandeis brief” (named after Louis Brandeis, who later became a member of the US Supreme Court), that is, a dossier of sociological, medical and educational statistical evidence combined with legal argument, which was designed to show on the facts that the proclamation in its implementation discriminated against coloureds, Indians and blacks, and produced harmful consequences.

Fifteen witnesses attested to the fact that the overcrowded conditions in the areas set aside for coloured occupation contributed to diseases such as tuberculosis, to family break-ups and delinquency.

The partial and unequal treatment that resulted from the application of the proclamation, I argued, contravened not only South African common law but also the international obligation to promote and respect human rights, which South Africa had assumed in signing the Charter of the United Nations.

The mention of South Africa’s international obligations under the United Nations Charter produced an outburst from the prosecutor. “Counsel is making a political speech,” he protested loudly.

I explained to the court that there was British authority for the proposition that a state’s international obligations should be taken into account in the consideration of the reasonableness of subordinate legislation.

The judge was not convinced by this or other arguments and ruled that the proclamation zoning Johannesburg for white occupation was valid.

A year later I presented the same argument to the Appeal Court in a joint appeal, with Browde arguing that the defence of necessity prevailed while I argued that the

proclamation was invalid on grounds of unreasonableness. Neither argument succeeded and the appeals were dismissed. The court did not, however, suggest that I had acted irresponsibly in questioning the correctness of its decision in Lockhat vs Minister of the Interior.

The political climate had changed dramatically in the two years’ moratorium on prosecutions afforded by the Werner case. The government had meanwhile determined that it would co-opt the coloured and Indian communities into the central political order by according them representation in Parliament. Consequently it was no longer politically expedient to continue with prosecutions under the Group Areas Act.

The Werner case convincingly demonstrated that a losing case might be politically successful. For me this was important, because I had had arguments with colleagues in Actstop about undertaking cases that might have positive political and social results even if they were likely to fail in court. Werner clearly vindicated this position.

This is an edited extract from Confronting Apartheid: A Personal History of South Africa, Namibia and Palestine (Jacana). John Dugard was a founder of the Centre for Applied Legal Studies, and has done human rights legal work all over the world.

A merry dance

Despite the breadth of the apartheid laws prescribing separation, there remained many areas of human and social interaction that were not covered by law. The city centres of South Africa were racially mixed. There were separate counters for the races in the post office and other government offices, but not in shops in most cities.

The law did not prohibit persons of different races from attending church services (although an attempt was made to do this) and from most forms of social interaction. Some organisations, such as the Institute of Race Relations and the Christian Institute, were open to all races. Foreign visitors often expressed surprise at the amount of racial mixing in shops and hotels in the major cities, in professional life, in church life and in interracial bodies.

The police believed that the law went further than it did, as was illustrated by a strange personal experience. One cold winter night shortly before midnight, I received a call from a friend who had been at a racially mixed dinner and dance party in Johannesburg organised by a group of radical clergy. At 11.30pm the police had disrupted the party and arrested them on the charge of interracial dancing. They had been taken to John Vorster Square, the police headquarters, and I was asked to secure their release on bail.

I drove down to John Vorster Square and asked the desk officer why my clients were being held. “There were blacks and whites dancing together, and this is against the law,” he said with disgust.

“There is no such crime,” I said.

“Of course there is,” he replied and went off to consult his colleagues. Half an hour later, after consulting a lawyer, he returned. “You are right,” he said angrily, “but we are charging them instead with breaking the curfew law, which prohibits blacks from being in white areas.”

“But, officer,” I replied, “the curfew only comes into force at midnight and they were arrested at 11.30.”

Very reluctantly, and angrily, he was obliged to release my clients, who later sued successfully for wrongful arrest.— John Dugard