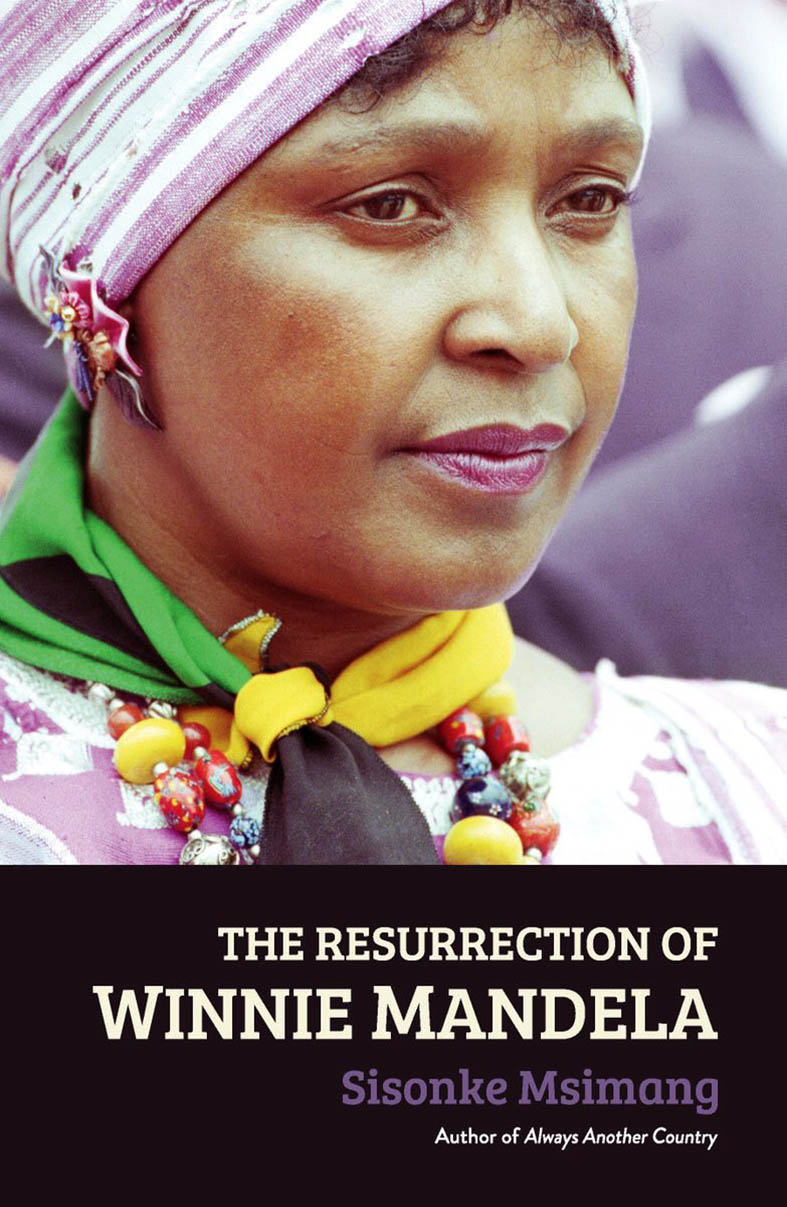

Photo: Peter Magubane

In her introduction to The Resurrection of Winnie Mandela, author Sisonke Msimang states unapologetically: “I will not pretend otherwise: I am interested in redeeming Ma Winnie.”

This makes me a little nervous as a reader. Despite my own respect for Winnie, I couldn’t help but wonder whether I really wanted to continue reading. Would Msimang’s proclaimed bias result in a skewed narrative that would choose not to interrogate some of the uncomfortable truths about Winnie? This would be a departure from Msimang’s usually balanced commentary. I chose to read on and found I had nothing to worry about.

The book lays out Winnie’s life in nine chapters between the introductory and concluding chapters. They are written in address mode either as though Msimang is reminding Winnie of who she is and her place in history or as though, in working to resurrect her, she must remind her why her presence in our national narrative is required.

In the Mbizana and Johannesburg chapters, Msimang recounts Winnie’s early years in the village and later her arrival in the city. In the earlier chapter, Msimang locates Winnie in the history of the Eastern Cape. She does this by questioning the flawed and irritating apartheid narrative that Southern African was uninhabited before 1652. (There is a little wordplay that makes a reader smile, given that this is a Winnie Mandela narrative.) “The white settlers never left. They were gifted land by van Riebeeck who had no authority to do this since the land was not his.” Instead they multiplied and had a highly negative effect on the locals they encountered.

Msimang fast-forwards to the Frontier Wars in the 19th century. It is here that she places Winnie’s fight for injustice alongside that of 19th- century heroes Maqoma and Hintsa.

She paints a portrait of a city that was then a little over 50 years old and its policies towards black people in general and black women in particular. Black women are, by turn, despised and tolerated in this white world, and the belief is that black men will keep them in check.

Winnie’s meeting and eventual marriage with Mandela is laid out in its own chapter, titled Nelson. Msimang highlights that Winnie was already politicised, attentive to injustice and spoke up against it prior to meeting Nelson. Msimang draws out this point because the assumption too often is that Nelson converted Winnie to politics. And that Winnie as a political being in her own right is something the reader keeps seeing. Indeed, this is further emphasised in the next chapter, Prison, which recounts Winnie’s diary of her incarceration, 491 Days. “You decide to commit suicide, but in a gradual way that will not shame Nelson and the girls … You want to die in a way that will be read as political — that will highlight the cruelty of the regime and the ‘terror of the Terrorism Act’.”

Miraculously, she manages to survive when apartheid doctors see her immense weight loss and take her to hospital.

The banishment to Brandfort also gets its own chapter, but it is in the Soweto and Trials and Tribulations chapters that I believe Msimang ably handles a difficult subject. Here, she addresses the infamous Winnie necklacing speech and places it in the ANC narrative of the 1980s. She brings out the statements of respected ANC and Umkhonto weSizwe stalwarts such as Alfred Nzo and Chris Hani and the announced policy on violence from OR Tambo. Nzo, then secretary general of the ANC, is reported in the London Sunday Times to have said: “Whatever the people decide to use to eliminate those enemy elements is their decision. If they decide to use ‘necklacing’ we support it.”

Msimang refuses to pretend that this sort of violence was not in line with the ANC just so that the ANC can continue a narrative that sacrifices Winnie as a rogue comrade who advocated violence alone rather than someone who was following party policy. Msimang interrogates the collection of Stompie and three other boys from cleric Paul Verryn, Stompie’s death and later that of Abu Baker Asvat, using both print and broadcast sources. In the same way she highlights the ANC’s complicity in calling for violence in the 1980s, the writer also refuses to sanitise Winnie even as she resurrects her.

Msimang’s book may fall short of expectations because, in a South Africa that’s too often black and white, those who have canonised Winnie as the patron saint of black women’s emancipation may take offence.

But Msimang is nothing if not an equal opportunity offender. She is also likely to exasperate those who, even after her death, continue to vilify Winnie. In refusing to do so, she questions such injustices towards Winnie, which includes how Harry Gwala, implicated in numerous political assassinations, was celebrated as the Lion of the Midlands.

In the South Africa of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission, she questions the dedication of more time to Winnie’s case than those of numerous apartheid police and soldiers. And she questions the sharing of a Nobel peace prize between a political prisoner and a commander-in-chief of the apartheid state.

Msimang’s The Resurrection of Winnie Mandela is well written and easy to read, which is as reflective as it is poetic in parts.

I couldn’t help but wonder, however, at the inconsistency of the references to Winnie in parts and Ma Winnie in others. Further, I was curious about the reference in the title and in the text post-divorce to Winnie Mandela instead of Madikizela-Mandela. In a text that sought to show Winnie as a political being in her own right without the shadow of her former husband, I found this particularly peculiar.

That said, Msimang’s book ends on a positive note. I can only hope that her belief in South Africa’s ability to self-correct, so that we may not need to resurrect our heroes and heroines, triumphs over my cynicism about our ability to do so, which is the result of not avoiding the news often enough.