(John McCann/M&G)

A detailed analysis has called into question the performance of the Government Employees’ Pension Fund and has highlighted what it deems to be persistent trouble at Africa’s largest pension fund.

In research done for the Association for the Monitoring and Advocacy of Government Pensions (AMAGP), Christo van Dyk, a retired senior manager at the auditor general, warns of emerging problems at the fund, which could have major long-term consequences for its sustainability.

His analysis builds on similar work done early last year on the fund’s financials, which the GEPF rejected outright.

But the AMAGP, which consists of former and active civil servants and was set up in 2016, maintains that the problems remain. In a statement earlier this month, it questioned the fund’s sustainability given its declining yield on investments and an “astronomical rise” in costs.

In his analysis, Van Dyk highlights, among other things, growing beneficiary liabilities alongside a widening contributions gap; the rising costs being paid by the fund under the current board of trustees; and the poor performance of the fund’s investments, particularly under the management of the Public Investment Corporation (PIC).

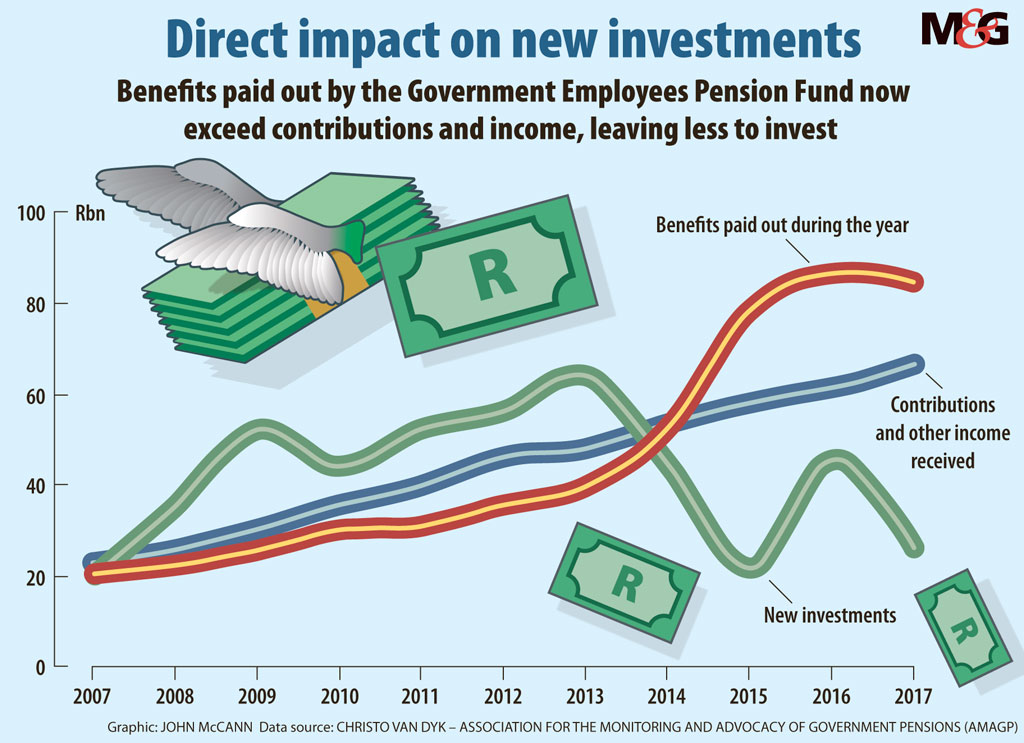

These factors are contributing to a decline in the cash being generated by the fund, which should be used to pay out benefits. Instead, Van Dyk says, member contributions are being used to pay beneficiaries rather than being invested to generate returns. According to him, from 2015 to 2018, under the current board, R257-billion was collected in contributions but only 59%, or R150-billion, was channelled into new investments.

“In essence, the GEPF used R107-billion over the four years to defray current expenses or benefits,” says Van Dyk, adding that this money should have been invested.

In terms of costs, his analysis suggests a sharp spike in recent years. He compared the costs incurred by the GEPF to manage its assets under previous boards against those of the current one. He calculated that they had increased 28 times since the time of the board chaired by Martin Kuscus, whose term ended in 2010.

In relation to net cash flow, expenses have grown disproportionately, from a low of 0.58% to 25.23%. A key factor in these increased costs is the fees for external asset managers, argues Van Dyk.

Although the PIC primarily manages the GEPF’s assets, it may appoint external fund managers to handle part of the portfolio. According to the GEPF’s most recent report, about 30 external managers were used by the PIC.

Van Dyk also questions the returns made on the GEPF’s assets. Although the GEPF reported growth of more than 8% last year, he argues that this is not all actual year-on-year capital growth but includes R56-billion in contributions received from members that are invested. The actual growth rate is 4.6%, according to Van Dyk.

His research also draws attention to a growing shortfall in contributions required from the employer, in this case the government. This issue was highlighted in the last actuarial valuation report done for the GEPF in 2016. It noted the shortfall between the required employer’s contribution rate — an average of 15.6% of pensionable salaries — and the actual contribution rate of 13.5%, which amounted to R6-billion a year.

The acturial report also noted that the lower than-expected investment returns had become a substantial strain on the fund.

The AMAGP has questioned the delay in the release of a new, updated actuarial valuation report, which was due in 2018.

The GEPF’s 2018 financials noted that its minimum funding level, as in the 2016 actuarial report, was 115.8%, meaning that it has enough money to meet its liabilities in the immediate future.

However, its long-term funding level has declined in recent years, reaching 79.3%, below the board’s target of 100%. It includes making provisions for unforeseen events, such as a major market collapse, the fund’s principal executive officer, Abel Sithole, said in December last year.

But to protect the fund “absolutely”, there would be concomitant cost because far more money would have to be set aside and could not be actively invested. “Right now, it’s not a concern for the fund at all,” he said at the time.

This week, the fund said it would not answer the Mail & Guardian’s questions because it had “previously … received similar questions from AMAGP, which we responded to”.

In a statement in April last year, published by Biznews, the fund rejected the association’s allegations. It attributed the cash-flow problems to “increases in resignation whilst the membership has not been increasing over the past five years”. The resignations were by members who had been with the GEPF for a long time and whose payouts were substantial.

It described the AMAGP’s arguments as “irresponsible” because they created “unnecessary anxiety amongst our members and pensioners, which often leads to members and pensioners resigning”.

It stressed that the GEPF was a defined benefit fund, which meant its members would receive their benefits irrespective of the investment performance of the fund.

The fund is underwritten by the government, so if the GEPF cannot meet its obligations, the state has to step in.

But Van Dyk says this may not assure complete protection. The GEPF is included as a contingent liability in the state’s budget but no allocation is provided for it.

The treasury, however, says the GEPF’s assets are more than sufficient to cover the best estimate of its liabilities and therefore there is no liability to the government.

No specific amount is provided for under contingent liabilities, the treasury says, because, with “the proper governance arrangements in place and a healthy funding level, it is unlikely that the contingent liability will materialise in the foreseeable future”.

The actuary’s recommendations that the state’s contribution be increased is being considered by the treasury, it says, and the report’s recommendations are “being discussed with the GEPF on an ongoing basis”.

Niel Fourie, the public policy actuary of the Actuarial Society of South Africa, says several things could affect the funding levels of a defined benefit scheme such as the GEPF, including the performance of the market, which has been relatively poor in South Africa recently.

Above-inflation salary increases for government employees would also have an effect on the fund’s liabilities, although the GEPF is very well funded compared with similar schemes internationally, Fourie says.

The AMAGP’s concerns came to light as Judge Lex Mpati’s inquiry into allegations of impropriety at the PIC got under way this week,

The GEPF recorded impairments of more R7.3-billion last year, up from R994-million in 2017, after it had to write down several controversial investments, including those in the Independent Media group, Steinhoff’s empowerment partner, the Lancaster Group, and VBS Mutual Bank.

The Public Servants’ Association says in a statement released last week that it is disturbed by reports of the GEPF’s cash-flow problems at a time when “the GEPF has written off billions in investment losses”. It cautions the PIC and GEPF to exercise due diligence when dealing with public servants’ pension investments.

Van Dyk says he hopes the inquiry will shed light on these investments and the effect they have on the fund’s performance. “Any investment that is not productive places the other good investments under pressure,” he says.