Transporting water: Makhandas drought means residents are rationed to 50 litres a day. Masonwabe Mangany (left) and his cousin Sibusiso Metu walk for two and a half hours a day to collect water from a trickling tap. (Delwyn Verasamy)

In the sweltering early morning heat, the fresh springwater glistens as it trickles from a pipe at the side of the N2 highway near Makhanda, formerly known as Grahamstown. Cars whoosh by, and the sandy ground crunches underfoot as residents head for the water.

Many come from the town centre, with their cars loaded up with containers. Unless they are first in line, they have to wait for at least an hour to get their turn at the tap. For some, this is where the cleanest water can be found in a town where concerns are growing about the quality of water coming from old pipes. For others, this water is a life-saver.

Sibusiso Metu (32), sporting a dagga-leaf print hat, is carrying a black backpack. He shows no signs of fatigue from the hour-and-15-minute walk to the spring from Joza township on the eastern side of Makhanda. It’s 8am and the air is heavy.

Metu puts his backpack down. He and his cousin, Masonwabe Mangany (31), unpack and line up their plastic bottles. They fill them from the spring, which trickles from a narrow pipe that serves as a tap. A few months ago, water gushed from it and residents could fill containers quickly. Now it takes at least five minutes to fill a five-litre container.

A sign at the entrance to Makhanda explains why the spring is running slower than normal: “You are entering a water-scarce area.”

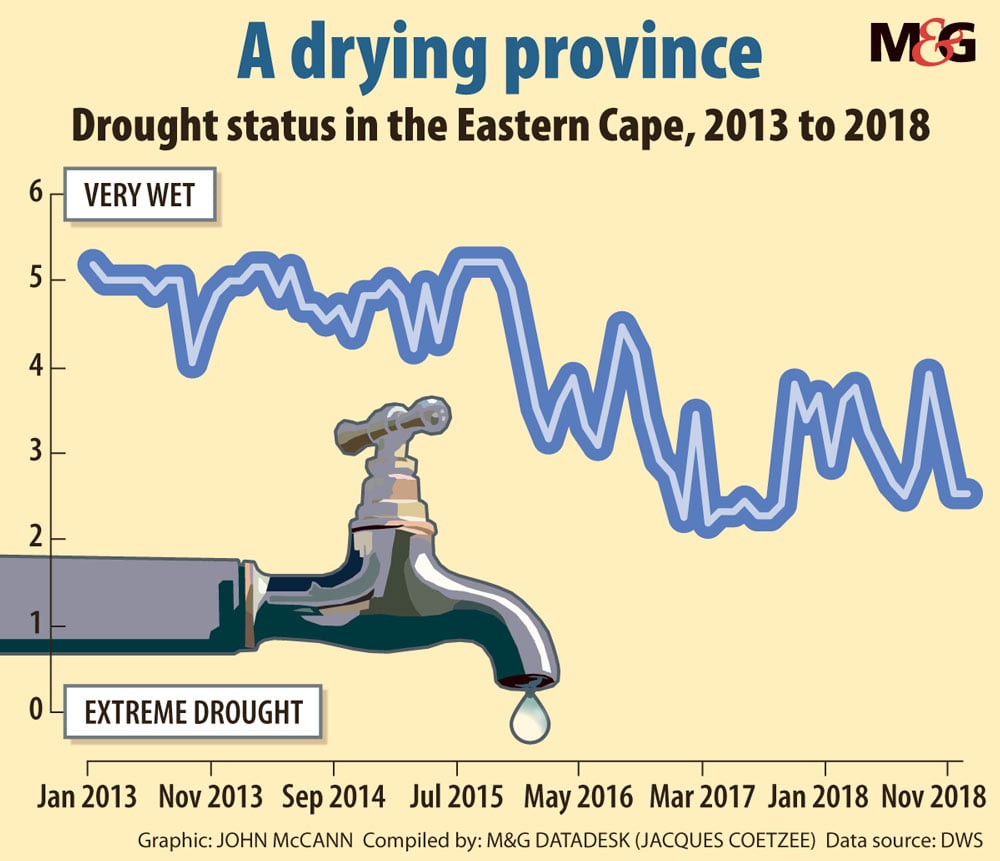

Makhanda is suffering in a drought. Jojo tanks are dotted all around the townships and suburbs; people are trying to catch water. They have been rationed to 50 litres a day a person.

But the drought isn’t the major cause of the water shortage — it is because of poor infrastructure, which the municipality has failed to maintain, creating what residents believe was an avoidable crisis.

Most water tankers don’t work (Delwyn Verasamy)

Most water tankers don’t work (Delwyn Verasamy)

It has also exacerbated the town’s informal racial divide. White people live in the town centre and surrounding suburbs, and most coloured and black people live in the poorer suburbs and townships.

The water supply helps to enforce this segregation. There are two sources of water in Makhanda: on the west side of town, people rely on water from the Settlers Dam. It is currently at 12.1%. On the east side, where the townships are, water comes from the Orange River scheme and is treated at the James Kleynhans water treatment plant.

It is among the most important parts of Makhanda’s infrastructure. It has the capacity to treat 10 megalitres of water a day. But a worker there says it currently produces 13 megalitres a day. He acknowledges that by pumping out an additional three megalitres a day it is affecting the quality.

Divide: Water for the Joza informal settlement comes from the overused James Kleynhans plant, where overdemand is affecting quality (Delwyn Verasamy)

Divide: Water for the Joza informal settlement comes from the overused James Kleynhans plant, where overdemand is affecting quality (Delwyn Verasamy)

But if there is no rainfall and the Settlers Dam runs dry, as is expected by mid-February, then the whole town will have to rely on a supply built for the townships alone.

MBB Consulting Engineers is helping the municipality to manage its water. Its managing director, Peter Ellis, says the plan is to shut off the Kleynhans supply to the townships for two days to allow the west to get a supply and vice versa until enough water is being treated. He is aware this might put a strain on residents, who will have to share a single source of water that feeds the poorest residents.

“That’s where the community gets involved. I have brought this to council and I told them they need to go and talk to their constituencies. You need to get buy-in from the community.”

Going, going: Green bowling club lawns may soon be a thing of the past if the town’s water supply runs out (Delwyn Verasamy)

Going, going: Green bowling club lawns may soon be a thing of the past if the town’s water supply runs out (Delwyn Verasamy)

The only way to avoid the two-day cycles is if the Kleynhans plant is upgraded to treat the 20 megalitre demand from the entire town.

But township residents claim that, as it is, the water is not being properly treated.

“Even if you are washing with the location water, you will find we are having pimples, your skin is itching. The problem of water, it’s a big crisis, because those who can’t come and collect water here, they are getting sick often in the location. Some of them, they have stomach aches,” says Mangany.

For the two men getting water from the spring, clean drinking water has become a luxury. Purified water costs R1 a litre, which they can’t afford.

When they have filled their containers, they will each be carrying 20 litres in their backpacks on their journey back to Joza. That is used only for drinking and will last them for three days. Then they will once again have to walk to the spring to fetch more.

Share: If the Settlers Dam runs dry, the town’s suburbs will also have to rely on the James Kleynhans water plant, which is already due for an upgrade (Delwyn Verasamy)

Share: If the Settlers Dam runs dry, the town’s suburbs will also have to rely on the James Kleynhans water plant, which is already due for an upgrade (Delwyn Verasamy)

An old problem

For many, the circumstances are not new. Little maintenance has been done. The pipes supplying Makhanda often leak and the water is often shut off, particularly in the townships, without warning or explanation. This has been going on for years.

The crisis could have been limited if the municipality had upgraded the Kleynhans water plant. That would have cost R170-million. The Makana local municipality, however, has a history of poor money management. The municipality spent 0.97% of its budget on maintenance and repairs from July 2016 to June 2017, according to data from the treasury. During the same period, Makhanda also underspent its budget by 73.96%. A 2017 plan to upgrade the plant went nowhere.

In 2015, the municipality was performing so badly that it was placed under administration. An investigation, the Kabuso Report, revealed internal misconduct, suspicious hiring and financial irregularities. In one case, the investigation revealed that the municipal spokesperson at the time, who would go on to become the strategic manager in the mayor’s office, had received irregular “additional benefits” amounting to R196 613 between September 2012 and January 2014. He had also received a salary increase, from R37 500 a month to R40 265.

In 2012, the spokesperson tried to explain to residents that the water in Makana was not toxic. He was dismissed in March 2014.

These issues still haunt the town, because activists believe they have not yet been dealt with.

Active citizens

Ayanda Kota, the chairperson of the Unemployed People’s Movement, is a veteran activist in Makhanda. He has joined business owners from the suburbs to form a coalition that has brought people together across race and class lines.

The protests of this coalition resulted in a petition with 22 000 signatures, demanding that the town be placed under administration. The petition was delivered to the council in November last year, and the mayor at the time, Nomhle Gaga, left office.

Veteran activist: Ayanda Kota, the chair of the Unemployed People’s Movement, wants Makhanda to be put under administration again (Delwyn Verasamy)

Veteran activist: Ayanda Kota, the chair of the Unemployed People’s Movement, wants Makhanda to be put under administration again (Delwyn Verasamy)

But, for Kota, the removal of one mayor to be replaced with another isn’t enough. He says the issues from 2015, when the town was first put under administration, must be investigated by the Special Investigating Unit and the Hawks. He believes that the ANC-led council and the councillors are not up to the task of cleaning up the rot that has been left by their colleagues.

“It’s like rearranging the deckchairs on the Titanic,” he says.

Makana’s new mayor, Mzukisi Mpahlwa, elected just two weeks ago, admits that things are bad. He has taken up the position at a time when confidence in local politics is at an all-time low.

Kota wants Mpahlwa gone and the town to be put under administration again. The coalition is also preparing court papers to demand that the council should be dissolved and that a by-election is held.

New broom: Mzukisi Mpahlwa, Makhanda’s newest first citizen since Nomhle Gaga left office amid protests, says he deserves a chance (Delwyn Verasamy)

New broom: Mzukisi Mpahlwa, Makhanda’s newest first citizen since Nomhle Gaga left office amid protests, says he deserves a chance (Delwyn Verasamy)

Mpahlwa believes his administration deserves a chance. He says Makana’s problem is essentially a shortage of funds. For example, the municipality is too broke to fix the trucks that would be used to deliver water to townships.

Referring to complaints about dirty water, Mpahlwa says water stoppages are the result of the municipality shutting off water, giving the reservoirs time to fill up before the water is pumped to the treatment facility. He says, according to experts advising him, this is the reason why water quality is compromised.

It wasn’t me

As a result of Makana being broke, Makhanda is broken. Vehicles jolt in and out of potholes in town. In the township, many roads are gravel. Rubbish lines the pavements throughout the town.

Mpahlwa knows the problems. The normal spending on municipal staff in South Africa is 35% of the budget. In the Makana municipality, where the mayor’s office is in the Makhanda town centre, the expenditure on staff is 43%.

Added to that, revenue collection is low. Most municipalities’ collection rate is 95% but Mpahlwa says Makana’s is 76%. He admits his predecessors have done the municipality a disservice but he won’t say who exactly should be held accountable.

“Obviously, it can’t be me. I’m just two weeks in the office.”

There is also rampant speculation about ghost workers in the municipality. In March 2016, Joza resident Mbulelo Pikoli said he was surprised to find he had been employed by the municipality and was receiving a salary of R4 500. He told the local Grocott’s Mail newspaper that he had never worked for the municipality but he is registered as having been employed there since 2013. The newspaper has reported on a litany of similar complaints and municipal failures.

Pikoli’s story is just one case about a ghost worker but residents believe the practice is widespread. A verification process is now under way by the municipal corporate services department to determine who is genuinely employed in Makana and who is not.

In the midst of this financial quagmire, MBB announced on Tuesday that it had depleted the available funds and could no longer continue to fix leaks; R10-million has been spent. But another R10-million has been provisionally approved by the national department of water and sanitation for the engineering firm. The money will be released when the department signs a memorandum of understanding, which will release at least R20-million for drought relief.

Additional funding is also being made available, as agreed to in the memorandum, to service the Kleynhans water plants. The upgrades are expected to be complete in mid-2021.

Meanwhile, Mangany and Metu will still trek to collect water. For Metu the walk has to be done; it’s a necessity in a situation where clean water has become scarce.

“We grew up learning that water is life but that water we have in the location is different. We no longer say water is life. Water has changed for us, because only this springwater is life. It’s a painful thing.”