Bubble: Palladium, a vital element in many catalytic converters, now costs upwards of $1?500 an ounce

Some South African platinum mining companies have started to come up for air, after years of low prices for the precious metal accompanied by deep cost-cutting and restructuring.

But it is not a change in the fortunes of platinum that has thrown these companies a lifeline; it is the stellar price rises of particularly its sister metal palladium, according to experts.

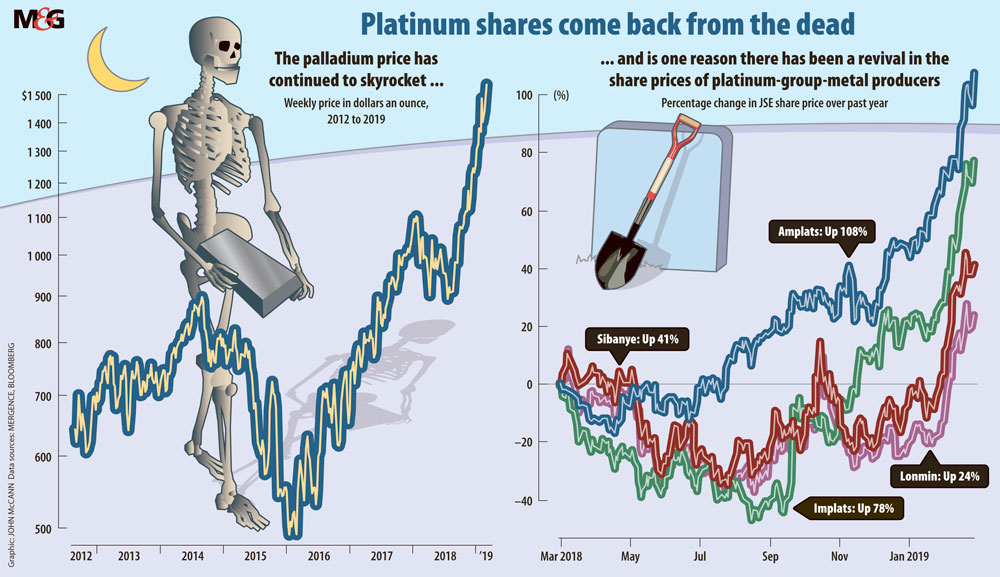

Palladium hit record high prices of more than $1 500 an ounce this year, up from about $500 a few years ago. This has been accompanied by increases in the prices of other platinum group metals (PGMs), most notably of rhodium. This has helped to buoy the financial performance of several local companies.

But the palladium price increase has already sparked reports of a bubble developing, although some market players remain bullish about its prospects.

Palladium, which is mined alongside platinum and other lesser-known PGMs such as rhodium, ruthenium and iridium, is a key element in the catalytic converters (which help to control harmful emissions) of petrol vehicles. Platinum is typically used in the catalytic converters of diesel vehicles.

According to Peter Major, Mergence Investment Managers’ director of mining, platinum accounted for 66% of the revenue of South Africa’s platinum industry a few years ago, but barely 40% today.

Palladium now accounts for nearly 36% of revenue and rhodium 16%, he says. In addition, the lesser-known PGM metals, including iridium and ruthenium, which barely constituted 1% to 2% of revenue a few years ago, are now more than 5% combined. This and the depreciating rand has meant platinum shares are doing much better, Major says.

The recent results announcements and operational updates of major platinum mining companies are shot through with a seam of positivity about the performance of other PGMs, notably palladium.

Although it remains in the red, Sibanye-Stillwater revealed in its latest financial results that its losses decreased to R2.5-billion in 2018 from R4.4-billion the previous year.

The company, which mines both PGMs and gold, said the solid performance of its PGM operations has compensated for operational problems experienced by its South African gold operations, which are subject to an extended strike by the Association of Mineworkers and Construction Union.

The company announced the purchase of the United States-based Stillwater mine in late 2016, which produces more palladium than its local operations and helped to increase its diversification into PGMs. The group noted in its results that its dominant source of earnings is now its US PGM operations, which accounted for about 50% of its adjusted earnings before interest, tax, depreciation and amortisation.

After years of losses and extreme cost-cutting, fellow platinum producer Lonmin recorded a profit of $62-million in 2018.

The company, which is planning to merge with Sibanye, said in its financial results late last year that, although the platinum market remains depressed, both palladium and rhodium have greatly improved and platinum’s contribution to Lonmin’s PGM basket revenue has shrunk from 58% to 45%.

Palladium and rhodium, meanwhile, rose to 23% and 16% of the total revenue basket respectively.

In a production update released in February, Lonmin announced that conditions have improved sufficiently to spread out the roughly 12 600 job cuts announced in 2017 over a longer period.

Meanwhile, the world’s largest platinum producer, Anglo Platinum, reportedly declared its first dividend in six years after recording improved profits, and noted that it expected demand for palladium and rhodium to continue in 2019.

Palladium’s performance has really helped save the likes of Sibanye-Stillwater and Lonmin, says Major.

The continued rising demand for palladium in catalytic converters for petrol vehicles has helped push up prices. In addition, he says the Volkswagen emissions scandal has contributed to a decline in the sale of diesel run vehicles in Europe, while other markets such as China have seen massive growth in palladium-based petrol car and SUV sales.

He says manufacturers have been slow to switch from using palladium in petrol vehicles, despite the fact that platinum is much more abundant, much tougher and currently much cheaper. He seriously questions whether the palladium price can be sustained.

“If it doesn’t correct, I think it’s at least going to level off. I just can’t see palladium going any higher, nor platinum going any lower,” he says.

Johnson Matthey, which produces catalytic converters, says in its latest PGM market report that the deficit in the palladium market is expected to increase dramatically in 2019, with tougher emissions regulations expected to result in double-digit rises in palladium demand from European and Chinese vehicle manufacturers.

Recoveries from autocatalyst scrap should rise this year but the rate of growth in secondary supplies is likely to be lower than in 2018, and primary shipments are expected to be flat, the report says.

Peter Duncan, Johnson Matthey’s general manager for market research, says, although the company cannot comment on price forecasts, or the reported emergence of a bubble, it maintains the view that “the price of palladium is largely driven by the fundamentals of its market”.

“In such a currently illiquid market, there is always opportunity for price volatility but we believe that the significant deficit in the palladium market is supportive of continued price strength,” he says.

Although some substitution of platinum for palladium in petrol vehicles is ultimately likely, there are still technical and practical problems to overcome, so it is unlikely to occur rapidly, he says.

“It’s technically possible to replace some [of the palladium] in gasoline catalysts [with platinum], but more development work is needed to match the performance of existing … systems.”

Duncan adds, despite the price differential, there is little appetite by the automotive industry to add platinum, because its resources are severely stretched to meet

new tighter emissions standards, limiting potential development work and testing of new catalyst formulations.