As we have become accustomed, this years narrative will not be different. Broadcast around the country will be the numbing message of how courageous young people turned the course of history.

COMMENT

Commemorations are double-edged rituals. On one hand they express the will to remember, while on the other they are vital political practices for legitimisation. In the past, commemorating the June 16 uprising was an important tool for mobilisation and collective political action.

After 1994, the tragic events that took place more than four decades ago have been appropriated to make claims about who orchestrated the uprising, to rein in dissident views and pay lip-service to the abject misery that faces the majority of young people in South Africa today. In the course of this commandeering of the past, history is mangled and the independent role of youth is erased.

As we have become accustomed, this year’s narrative will not be different. Broadcast around the country will be the numbing message of how ‘courageous young people turned the course of history’. We will hear little about how the uprising was organised, how it spread, the duration of the protests, strategic blunders, how the protests ended as well the role of accidents and unplanned developments in the evolution of the rebellion. History gets flattened and we miss out how in Soweto, the Soweto Student Representative Council (SRC) coordinated the action while in townships there was an aversion to formal structures and elected leadership.

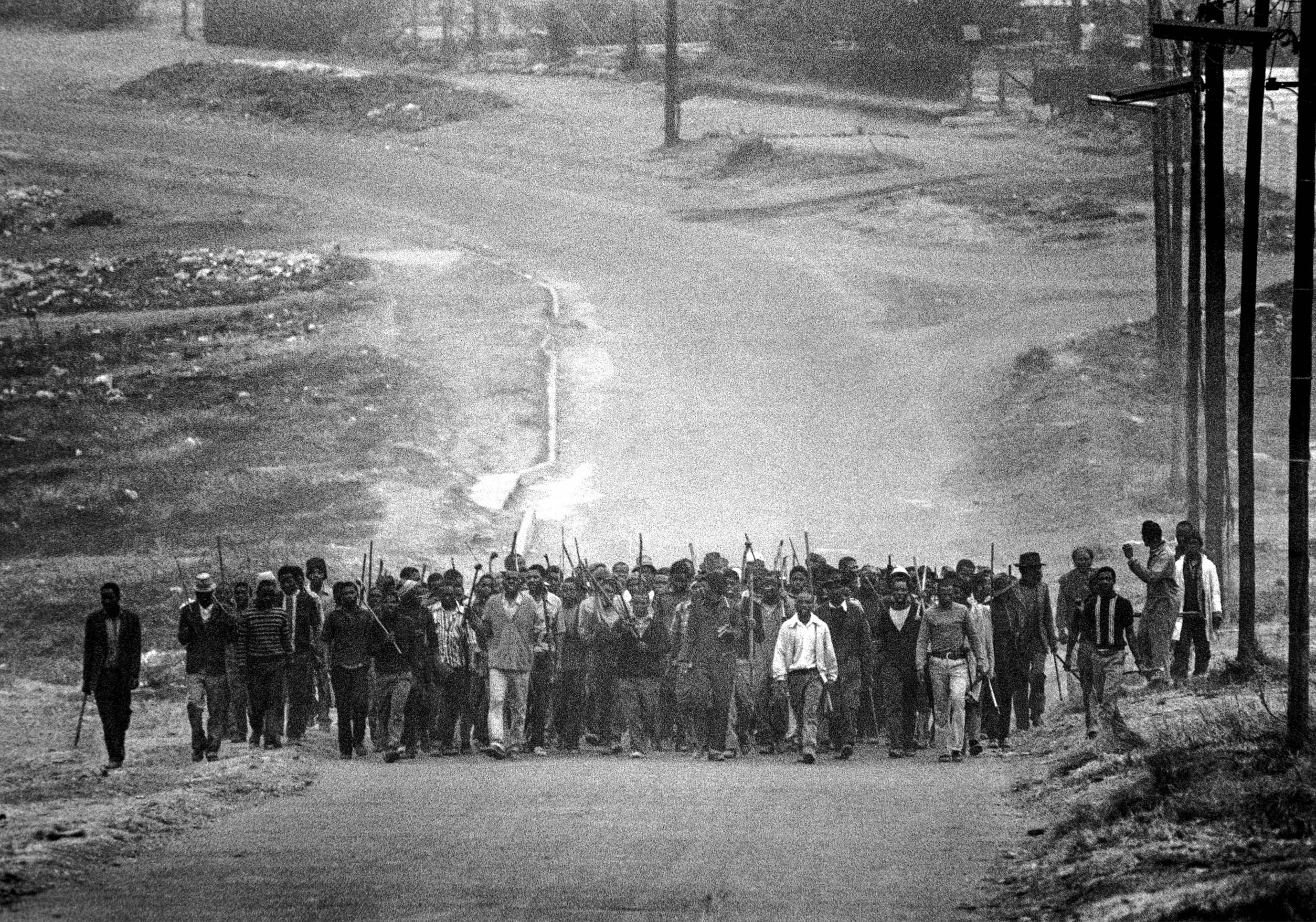

Like in any uprising, there were events in 1976 that were planned and there were others that were spontaneous. Unlike the portrayal of a singular event that we get at commemoration services, the revolt also went through episodes with ebbs and flows between June 1976 and January 1977. With the students from Langa, Nyanga and Gugulethu walking out of their classes in August, ‘Umbumbumbu’ as the struggle was called went through phases of formulating of demands, galvanising parents’ support and forging non-racial unity with schools outside of ‘black African’ areas. Each of the phases had specific objectives such as organising the march to the city centre, the two-day worker stay-away in September, ‘Black Christmas’ and the closure of township shebeens.

Anyone who was either a participant or observer of the student rebellion in Cape Town would know of the numerous meetings that were held with parents at Nonzwakazi Methodist church and the Old Apostolic church in Gugulethu. However acrimonious, meetings were held to garner teachers’ support for the campaign. Winning such support was crucial. With only four ‘black African’ high school and without parents’ support, the drive to have students who schooled in boarding schools outside Cape Town return to the city to join the boycott of classes would have been in vain.

Also never told in the mythologised history, is how throughout the uprising there were on-going negotiations with authorities and deputations to the Minister of Bantu Education MC Botha. For an example, after formulating their demands and with the help of Lagunya religious Ministers’ Fraternal, the regional director for Bantu Education DH Owens came on September 28 to a mass meeting at ID Mkhize high school to negotiate with the Cape Town students.

While not belittling the courage displayed, it is important to remember that the shock- troops of the revolt were teenagers. Youth cultures found their way into the uprising. To be a ‘proper comrade’ you had to wear a ‘wild look’ — uncombed hair and untucked shirts. It is therefore not accidental that the most popular slogans in Cape Town were ‘Black Power’ and ‘There’s no place like South Africa today’. The 1970s were the era of soul music and the second slogan was an adaptation of US singer Curtis Mayfield’s album There’s no place like America today, released in 1975.

Whereas the immediate demands were political in the narrow sense of the word and about the education, the uprising in 1976 was also an inter-generational conflict. Not scarred by repression like their elders, young people did not spare their parents as they took on the state and traditional political movements. As the uprising intensified, their consciousness also grew. The slogan ‘We want our damn country back’ began to accompany shouts such as ‘Black Power’ and ‘Amandla’. The hymnal song ‘Senzeni na’ morphed as young people added verses about ‘AmaBhulu zizinja/Boers are dogs’ and ‘Sono sethu bubumnyama/Blackness is our sin and crime’.

Old political movements were definitely caught off-guard. Having convinced themselves that the only way to fight the apartheid system was through armed struggle, the old political movements cautioned the youth for wanting to fight the regime with stones. Instead of tapping into the energies of young people to build a mass movement inside the country, the student movement was seen as a recruitment ground for liberation armies.

Equally, parents were bewildered. They could not understand the rebelliousness of their children. They could only find partial explanations from verses in the Bible about a prophesied time when children will rise against their parents. There comes a time, “For a son dishonours his father, a daughter rises against her mother, and a daughter-in-law against her mother-in-law; a man’s enemies are the members of his own household”.

Although recent scholarly research such as Julian Brown’s The Road to Soweto and Anne Hefferman’s Limpopo Legacy has tossed out the presentation of the 1976 uprising as an explosion triggered by the introduction of Afrikaans as the medium of instruction, there is still a tendency to give a Soweto-centric version of events. Within days, the protest spread to different areas of the country. In reached some townships earlier than others. But more importantly and what the Soweto-centric narrative misses is that as the protest spread like wildfire, it took different forms and focused on issues differently.

For an example, the students from Langa, Nyanga and Gugulethu walked out of their classes in August. The main reason for the walkout was not the decree that made the use of Afrikaans compulsory. The trigger was police brutality meted out to students elsewhere. As a response to enquiring parents and written in their placards, the students from the three townships said; “We sympathise with Soweto”. In his book Place of Thorns on the student protest, Tshepo Moloi notes: “In Kroonstad’s African township, students at Bodibeng high school demonstrated. But it was not because of Afrikaans. It was in solidarity with their counterparts in Soweto and elsewhere in the country”.

Clearly, students from ‘coloured’ and Afrikaans schools who took part in the uprising did so for their own reasons and as an act of solidarity. So were students in former ‘homelands’ were the decree on Afrikaans was not applicable. Although the introduction of Afrikaans may have been the trigger in Soweto, it is therefore important to show how the roots of the uprising can be found in the general political awakening amongst youth that goes back to the late 1960s with the formation of bodies such as the South African Students Organisation (SASO). Also critical is to show how the rebellion as it travelled, it took various forms.

In the volume that deals with protests in the 1970s, Thomas G Karis and Gail M Gerhart point to police reports of rising incidence of unexplained fires on white farms and sawmills in 1976. In Transkei and Bophuthatswana, the uprising became entangled with the movement against the planned ‘independence’ of these Bantustans. Although the “official versions” of the uprising have a straitjacket of one 1976, the revolt had tributaries.

The history ministerial task team that the Minister of Basic Education appointed in December 2018 to overhaul the history school curriculum has its job clearly cut out. The team has a responsibility to move us beyond a ‘patriotic history’ that acts as a commemorative plaque but to a curriculum that tells the past in more nuanced ways. In dealing with the 1976 uprising, the story cannot be told by attaching other centres as an add-on and afterthought. It will have to look at how the uprising travelled to different parts of the country as well as the forms it took as it moved beyond Soweto.

Dinga Sikwebu is a co-director for programmes at Tshisimani Centre for Activist Education. A Grade 9 student in 1976, he took part in the Cape Town uprising.