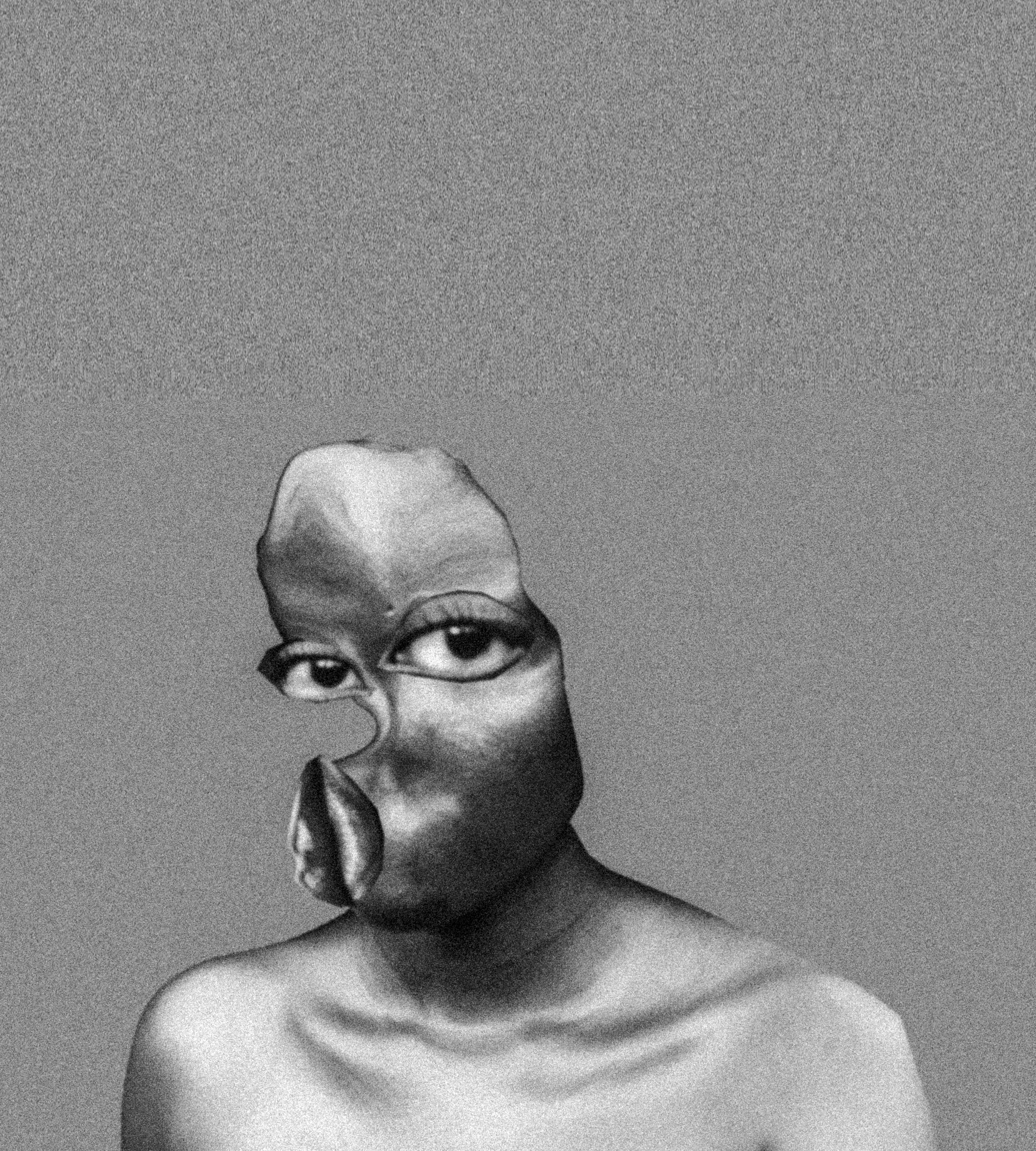

Signature style: Lunga Ntila uses distortion and collage-making when creating portraits, among them is Untitled (2019) (Lunga Ntila)

In the two years that she has been in the game, 24-year-old conceptual photographer Lunga Ntila’s name has been synonymous with the practice of distortion. Armed with a Nikon D5200 camera, natural light, a fabric backdrop and Adobe Photoshop, Ntila takes what Australian photographer Sorelle Amore refers to as the advanced selfie and places it in the territories of collage-making as well as expressionism and cubism.

She takes a photograph of her face, then cuts, deletes, duplicates, elongates and pastes features where they do not belong. The result is a body of work titled Ukuzilanda.

Thinking about you (Lunga Ntila)

The intention behind Ntila’s use of distortion is to expand people’s ideas of the self.

PROMOTEDMake this Summer the best everGet the Samsung Galaxy A30s and R250 Online Voucher for R299 PMx24 On Smart XS+ Buy Now.Vodacom | vodacom.co.za“There are parts of ourselves that we don’t know well enough to recognise but they are still very much a part of us. Like our ancestors,” Ntila says. “That’s what Ukuzilanda is about: fetching the fragments of myself that I have discarded and imagining the various forms that I can take on with them.”

Following this week’s events, an additional phrase that can be used to describe the emerging artist is “booked and busy” because Johannesburg’s art fair week sees her showing her work in three places. On September 11 Ukuzilanda, her first solo exhibition, opened at BKhz in Braamfontein and three additional works made their debut in Maboneng at the inaugural Underline Projects art show. Another artwork is at Art Joburg under Gallery Lab.

On the eve of this eventful week, the Mail & Guardian spoke to the emerging artist about taking up space, the validity of her practice and negotiating her commercial value while remaining independent.

The Ntila wave began last year when pop culture archiving platform Bubblegum Club wrote features on her work and Between 10and5 referred to her as a visionary to watch. She then went on to feature in printmaking collective Offset Culture’s Pictorial Nerve at the 2018 Art Book Fair in São Paulo, Brazil, and locally as a part of the Keyes Art Mile summer exhibition.

In talking about her emergence Ntila cites independent curator and one of the founders Underline Projects, Lara Koseff as “day one support” because she took Ntila on through Offset Culture. When asked about what drew her to the artist’s work Koseff says it was Ntila’s “fresh” recreation of the pictorial.

And although 2019 has seen Ntila’s work featuring at the Investec Cape Town Art Fair and Design Indaba recognising her as a part of this year’s emerging class of creatives to watch, Ntila is yet to settle into the idea of being a contemporary artist. “It feels like they just let me in as a guest and I’m having coffee,” she laughs shyly, cupping her cappuccino.

With a Vega School degree in creative brand communications, specialising in copywriting, a part of Ntila’s uncertainty stems from her lack of formal art training. This is in spite of the likes of Tony Gum, who has a degree in film, successfully treading territories such as this before her.

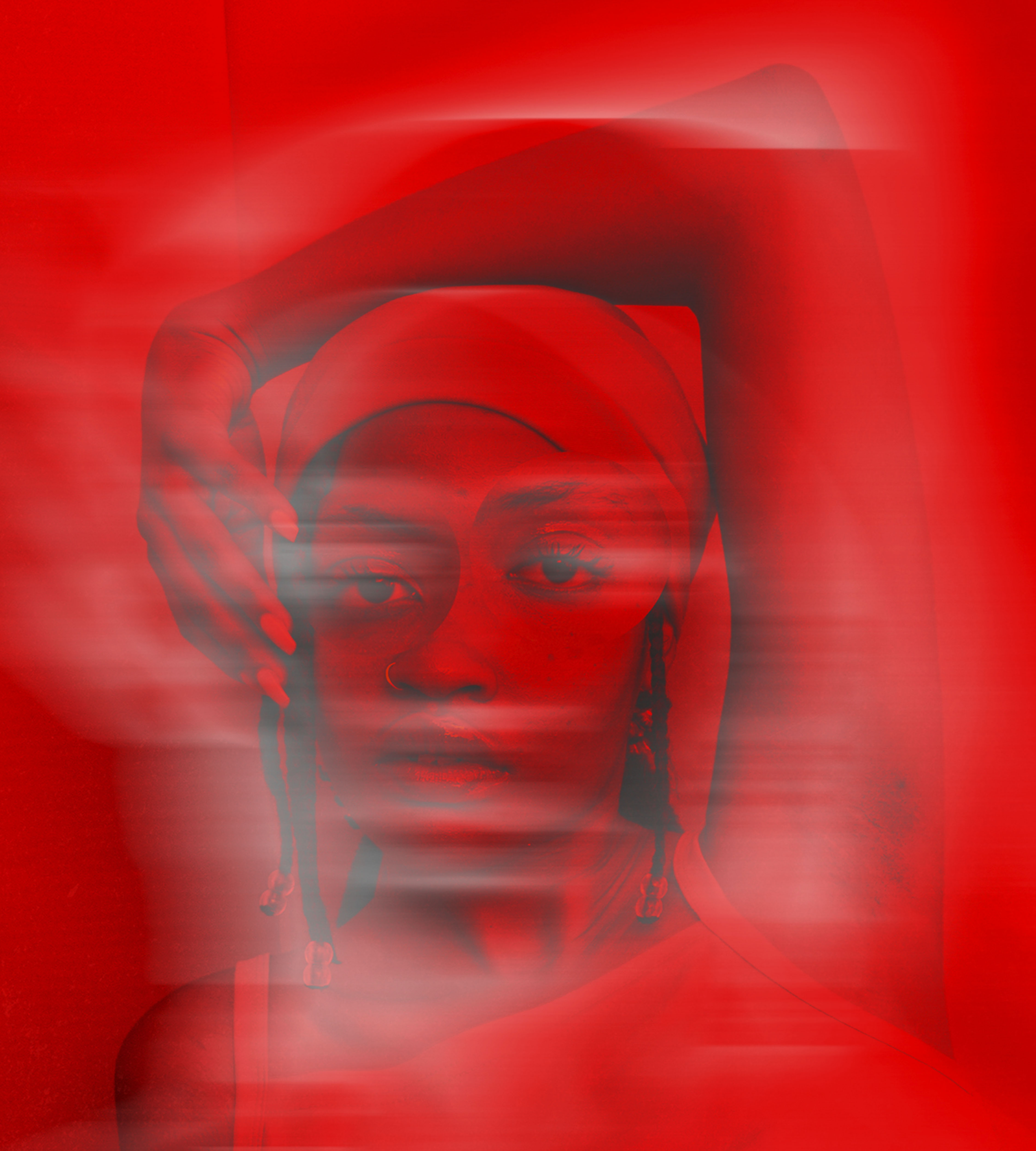

Other-worldly: Dazedby Lunga Ntila has an ethereal feel as the subject appears to be behind a translucent shroud (Lunga Ntila)

“The things I hear people say about collectors make me feel like the art world is reserved for traditional artists,” Ntila says. “I’m not sure how much alternative portraiture like mine sells without the clout that comes with gallery representation.”

“I think that formal art training gives artists a network from which to operate… if she was to learn the rules, she’d break them anyway,” adds Koseff.

As a result of questioning her validity, Ntila admits to remaining within the narrow confines of the work that people like. “Distortion has become my inevitable trademark,” Ntila shrugs. She says that whenever she is commissioned for photographic work, the clients insist on the inclusion of her signature disfiguration. “I give them what they want.”

Together with questions of validity that result in her arresting her expansion, Ntila adds that being an emerging artist without gallery representation comes with the challenge of determining her own worth while footing the expenses for production and printing. “The first time someone was interested in buying my work I called [photographer] Andile Buka and asked him about a good entry point. He suggested around R1 000 and R1 500 if I want to go home with a little something after printing costs.”

Two years later she has gained some traction and begun flirting with the idea of value appreciation. But seeing that she has sold no more than 10 prints, Ntila has stopped herself from acting on the thought of changing her pricing because “there’s no point in having expensive-ass pieces if no one is buying them”.

Such challenges are what encouraged Ntila to accept the invitations she received from Underline Projects and BKhz. Like BKhz, Underline Projects is an alternative curatorial platform that looks to inform and support the practices of independent artists and curators. In addition to the visibility the shows will garner, Ntila has used the opportunity to inform her practice.

By the end of the interview the conversation has shifted from one of celebrating her triumphs to one about the need to increase artists’ awareness of where to go for assistance. I say awareness instead of structures because Underline Projects and BKhz are not the only institutions in place to support independent artists. Rising artists also have access to tools such as the free Visual Arts Network of South Africa’s guide to art practice and networking platforms such as Creative Nestlings which — through interactive social media and public monthly talks — aims to democratise the knowledge that will connect and grow African creatives. And as Vansa’s director Kabelo Malatsi told the M&G last year, there is a need for such tools and platforms because, “the industry has no good standards for anything and we are not organised enough as a community, so exploitation is still rife”.