Iconic: Sócrates lines up before the World Cup match against Spain at the Jalisco Stadium in Guadalajara

‘My political victories are more important than my victories as a professional player. A match finishes in 90 minutes, but life goes on.” These are the profound and potent words of Sócrates Brasileiro Sampaio de Souza Vieira de Oliveira, known simply as Sócrates.

“On the field, with his talent and sophisticated touches, he was a genius. Off the field … he was active politically, concerned with his people and his country,” former Brazilian president Dilma Rousseff said in 2011, following Sócrates’ death.

Although he was a player with incredible flair and talent, it was his brilliant marrying of the game and politics that displayed his undeniable intellectual gift. Magrão (Big Skinny), as he was affectionately known, would stride on to the pitch sporting barely-there shorts, a jet-black beard and long curly locks that were either tucked under his trademark headbands or left dangling on his neck, and weave his magic.

Unlike most footballers, he didn’t turn professional until he was in his early 20s as he was studying medicine at the same time. Despite having ambidextrous football feet, he certainly did not regard himself as athletic and admitted that he had not honed his body for football’s athletic demands from a young age. Nonetheless, he started as a centre-forward in the late 1970s, before becoming a magnetic midfielder who won many hearts.

This is part of what made Sócrates so special: he was unlike any other footballer and barely conformed to expectations. The beer-guzzling chain-smoker, who could go through up to two boxes of cigarettes a day, wanted to be accepted for who he was. “I am anti-athlete. I cannot deny myself certain lapses from the strict regime of a sportsman,” he famously said.

Sócrates played for one of the greatest sports clubs in Brazil: Corinthians Paulista in São Paulo, a team founded by working-class men on the realisation that professional football clubs at the time were formed by — and for — the elite.

The best team to never win a World Cup

For the 1982 and 1986 Fifa World Cups, Sócrates was captain of the Seleção. This national team enchanted Brazilians; they loved the original football that was played to its own capoeira beat and roared their admiration in the stadiums, where a convivial spirit dominated.

In the words of Sócrates: “Football has an intimate relationship with dance, giving a platform to different forms of expression.”

Having won the World Cup in 1958, 1962 and 1970, Brazil did not expect to lose to Italy in the group stage of the 1982 edition of the global showpiece. The South Americans boasted “a constellation of stars” such as Zico, who played with zeal; Falçao, with flair; and Sócrates, with an easy pace under coach Telê Santana. Italy — who had until that match played mortifyingly badly — eliminated Brazil 3-2 with a Paulo Rossi hat-trick.

In praise of glory, not victory: Brazilian supporters celebrate a goal by Sócrates at a Fifa World Cup group-stage match on July 5 1982, played between Italy and Brazil. Despite the 3-2 score going Italy’s way, the Brazilian team was roundly applauded on their return. (Mark Leech/Offside/Getty Images)

In praise of glory, not victory: Brazilian supporters celebrate a goal by Sócrates at a Fifa World Cup group-stage match on July 5 1982, played between Italy and Brazil. Despite the 3-2 score going Italy’s way, the Brazilian team was roundly applauded on their return. (Mark Leech/Offside/Getty Images)

Sócrates’ talented Brazilian side might have not won a World Cup, but they hold a prominent position in the history of the tournament and the beautiful game. They are revered more than other teams that have won football’s ultimate prize.

The team was showered with love and adoration on their return to Brazil from Spain, reinforcing the idea that it was not about victories but about glory. The loss did not bother Sócrates as winning was not his priority. He has been quoted as saying: “Those who seek only victory seek conformity.” His focus was on the expression of football as art.

In a 2010 interview, he said, between gulps of Stella Artois and with bloodshot eyes, “I see football as art. Today most people see football as a competition, a confrontation, a war between two polar opposites … but to start with, it is a great art form.”

Watching grainy footage of old matches can send chills down the spine of even the most hateful rival. Sócrates’ Brazil played sumptuous and organic football with goals that gave new meaning to the term “joga bonito” — to play beautifully.

A recent match in November between Corinthians and their rivals, Palmeiras, at Estadio Municipal left much to be desired in terms of flair and artistry. But the atmosphere — in a game attended only by Palmeiras fans — was gripping, and the stadium was buzzing. In 2016, a bystander was shot and killed during a skirmish between Corinthians and Palmeiras fans, resulting in a ban against away supporters attending São Paulo derbies.

Corinthians no longer play like they used to, but they are still a politically conscious club. On the anniversary of the 1964 coup that President Jair Bolsonaro wanted to celebrate, Corinthians posted a tweet showing Sócrates from the back in kit that read Democracia Corinthiana with splashes of blood on it.

Scoring goals while attaining democracy

In 1964, the military junta usurped power through a United States-backed coup, removing left-leaning former president João Goulart from power. Sócrates imbibed democracy through his actions, having seen his father — a working-class man who worked his way up the ranks – at the receiving end of the suppressive hand of the dictatorship that tortured intellectuals and the poor, and killed off political rivals.

“I was 10 years old and remember my father burning books about the Bolsheviks. That started my interest in politics. The football came by accident,” he was quoted as saying.

The football pitch was one of the few places where players could express themselves without fearing a massive backlash from the brutal state, and where fans could enjoy games and escape the grim reality of their lived experience in a Brazil buckling under a repressive regime.

Corinthians consisted of a group of men with political awareness who wanted to bring an end to authoritarianism. Players felt restricted and disempowered as decisions were made for them by the upper echelons in football, and so they envisioned a new management system. The focus on democratic expression led to discussions not only about philosophy, literature and politics but also about a variety of socioeconomic and political issues faced by Brazilian citizens.

Words cannot describe the political importance of the socialist movement inside the club called Corinthians Democracy, which was co-founded by the leftist egalitarian, Sócrates. He used the team as a vessel for political awareness and for realising a democratic Brazil, essentially helping to catapult the country from military dictatorship to democracy.

“Basically, our aim was to democratise expression. Our group worked in the football world and we decided to vote on everything,” he said.

The politics of football

Politics was an outfit donned on and off the pitch, literally and figuratively.

Off the pitch, the team personified democracy by resolving to make inclusive and communal decisions that included even the cleaner. Decisions included when to have lunch, what time to meet for practice, when to have a toilet break and even if they should stay with the team hours before the game.

On the pitch, the team would often wear football kits featuring anti-dictatorship slogans in a clear and understated subversion. In one instance, Sócrates had a headband bearing the words “No violence”. The team wore a kit with the words “Democracia” and “Corinthians” emblazoned on the back in the font used by Coca-Cola, and in red to symbolise blood. In 1983, the team ran on to the pitch with a banner stating: “Win or lose, but always with democracy.” That was the year they won the São Paulo championship.

But they delivered perhaps their most important message before November 15 1982. Not a single syllable had to be uttered to convince Brazilians to vote when the players donned shirts that so plainly demanded action with the words “Dia 15 Vote” printed across the top of their black-and-white jerseys. It was instructive and direct, but did not state a political party.

It was unimaginable to even subtly state anything political under the oppressive regime of a military dictatorship, yet these political statements were made and clearly influenced a generation to fight the system and reimagine what football meant politically.

The people went out and voted, prompting the unorthodox captain, whose team decided to use football as a platform for creating political awareness, to charge forward with their efforts for the redemocratisation of the country.

In 1984, the movement drew 1.5‑million people to a rally in bustling São Paulo, demanding democratic presidential elections. Sócrates begrudgingly moved to Italy to play for Fiorentina for one season, after famously hinging his international transfer on the passing of an amendment allowing for presidential elections.

His political decision led to unhappiness in Italy, where football was not as flamboyant and organic. But he was rewarded when Fernando Collor de Mello came to power in 1989, following the country’s first presidential elections since 1960.

Sócrates eventually left football temporarily, focusing on his medical practice for a few years. His unwavering determination manifested itself again when he took a break from medicine and football to avail himself to the arts, writing and directing.

Half man, half amazing

The lanky midfielder was a prolific goal scorer, a technically gifted player who finessed the game for other players on the field with fluid attacking football and a magical back heel that prompted legendary striker Pelé to say that Sócrates played football “better backward than most players going forward”.

Before the 2014 Fifa World Cup, which was hosted by football-loving Brazil, Sócrates criticised the frivolous spending of public money on a private event. Brazil had only hosted the World Cup once before, but this time they had to host in the midst of political and social uncertainty.

In his last few days, Sócrates lamented the contemporary form of football, which, he said, had lost its true function of unleashing the art of expression. Football was no longer artistic, aesthetic and joyful. Instead, players were now tranquillised into subservience and focused on victory.

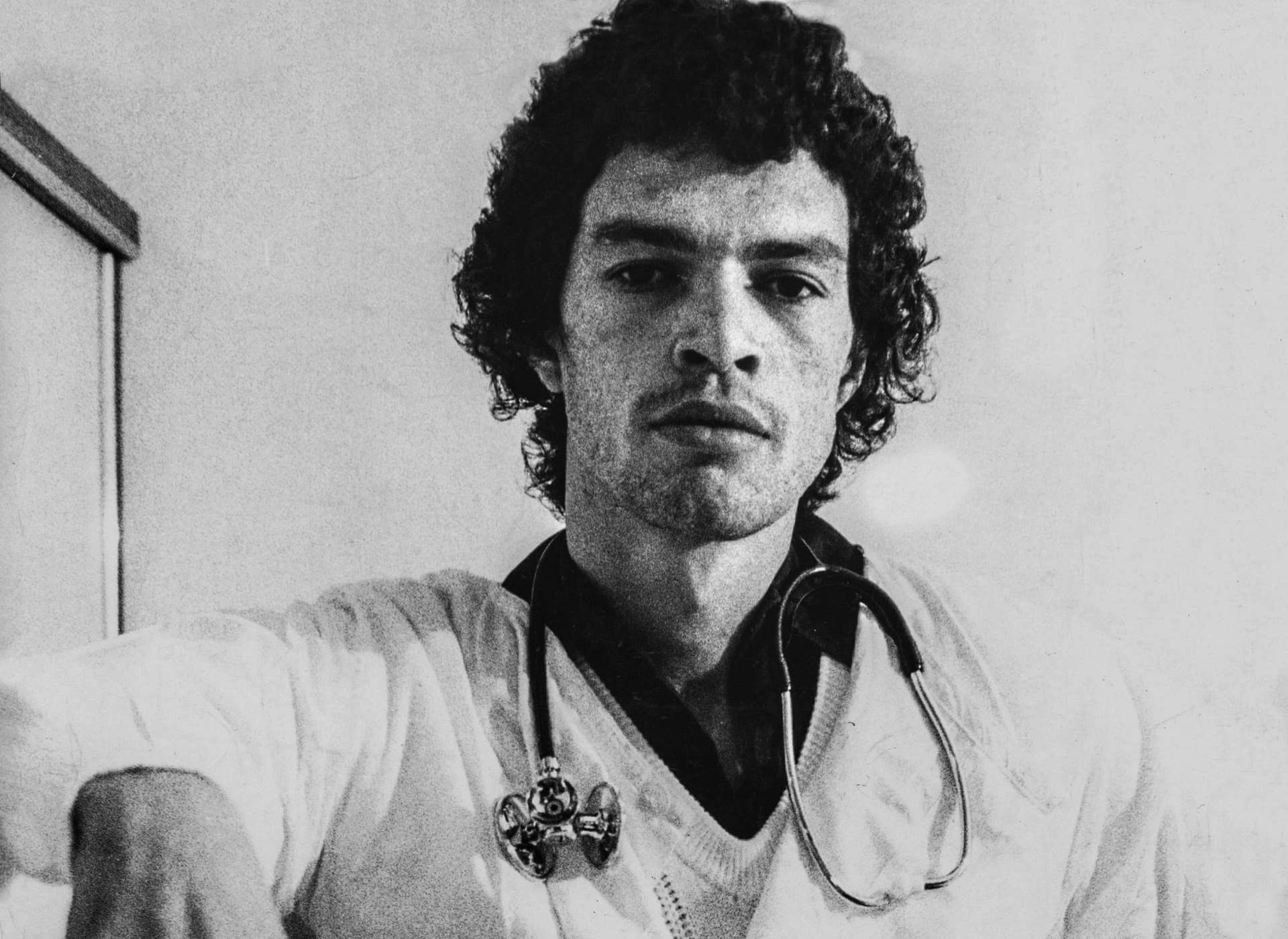

Dr Sócrates. (Alfredo Rizzutti/Agência Estado)

Dr Sócrates. (Alfredo Rizzutti/Agência Estado)

“To win is not the most important thing. Football is an art and should be about showing creativity. If Vincent van Gogh and Edgar Degas had known the level of recognition they were going to have, they would not have done the same. You have to enjoy doing the art and not think, ‘Will I win?’”

As a doctor, he treated his health with dreadful indifference and was hospitalised for liver-related illnesses for 24 days. He was on life support before succumbing to his ailments.

On the day of his death, Fiorentina – who were playing against Roma – honoured Sócrates with a minute of silence and saluted him with a victory. He had played 25 games and scored six goals for the team.

He won three São Paulo state championships with Corinthians: in 1979, 1982 and 1983. He earned 60 caps between 1979 and 1986, and scored 22 goals. He has been inducted into the football museum Wall of Fame near Estadio Municipal, formerly the Pacaembu Stadium, and home ground to Corinthians.

There are a number of eclectic reasons Sócrates will be remembered the world over. But primarily, he will be remembered for his political resistance to the dictatorship, for using football as an interlocutor and for bringing about a new sense of political awareness that was uncharacteristic of a footballer.

More than 1 000 people attended his funeral in Ribeirao Preto, São Paulo, and his name will without doubt continue to fall from the lips of generations to come.

This article was first published on New Frame

Brazil’s far-right kicks in

The involvement of Brazilian football players — current and legends — in politics has become a sore point for rightist critics. Many of the biggest names in the past three decades have declared their support for President Jair Bolsonaro, a pro-torture, anti-conservation homophobe who took office on January 1 last year.

A number of star players in the 2002 World Cup winning side alone voiced their support for Bolsonaro. These include Rivaldo and Cafu, who declared, “The captain of the five-time champions will vote for Bolsonaro.”

The most prominent of his supporters is Ronaldinho, the carefree genius with an endearing smile that was impossible to wipe off during his day. His endorsements of Bolsonaro shocked and hurt many around the globe who still revere him.

Ronaldinho and Rivaldo’s former club, Barcelona, has distanced itself from them, limiting their ambassadorial roles. It’s a far-cry from a recent past that saw Ronaldinho threaten to leave the pitch because teammate Samuel Eto’o was being racially abused.

In one Instagram post, he posed with a “17” shirt, a reference to Bosonaro’s victorious 2017 campaign. He wrote as the caption: “For a better Brazil, I want peace, security, and someone to give us back our happiness, I chose to live in Brazil.”

That, in essence, is where the support stems from. For super-rich former footballers, Bolsonaro and his conservative policies promise to protect their wealth and their standing in society.

Others, such as AC Milan legend Kaká and Felipe Melo, identify with the evangelism of the demagogue and believe he is instilling the correct Christian values.

Neymar and Gabriel Jesus are two big names that have implied their tacit support of the president, each having liked and responded to Bolsonaro’s posts on social media.

Of the more muted voices on the other side of the political divide, it’s Juninho who has spoken up the loudest. Lyon’s former Free Kick wizard even went as far as to move his family out of Brazil when the new government came to power. — Luke Feltham