The Moravian Church

has congregations around the world, with more than a million members. South Africa, with 103 000 members, has one of the largest congregations. (Photos: Jonathan Hendricks)

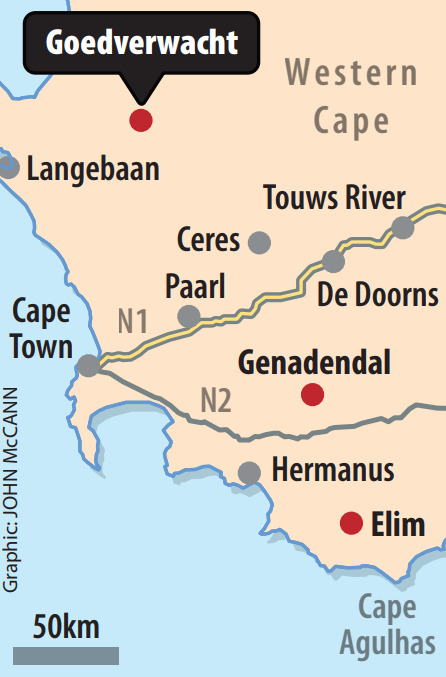

The rural town of Goedverwacht, 145km west of Cape Town and home to about 2 000 people, is not like any other town in the area — it is a Moravian mission station, one of 11 in the Western Cape.

It is also one of a number of mission stations where the residents are in the middle of a legal battle with the church over land, and the meaning of “ownership” in the context of a history of slavery and apartheid.

These battles, which will be precedent-setting, go straight to the heart of land reform and indigenous peoples’ rights in South Africa.

The Moravian Church doesn’t only have church buildings, bells and Sunday mass.

Rather it controls entire towns — mission stations — and hundreds of thousands of hectares of land. It even has its own financial services and property management company, MCiSA Holdings.

The church, which considers itself the owner of these small towns around the country and the surrounding agricultural land, where residents pay it taxes and levies, and live under its laws, has left many people dispossessed and disenfranchised.

Known formally as Unitas Fratrum or Unity of the Brethren, the Moravian Church is one of the oldest denominations of the Protestant Church, founded in 1457 in Bohemia in present-day Czechia.

The missionaries who came to South Africa as early as 1737 were German.

The church has congregations around the world, with more than a million members. South Africa, with 103 000 members, has one of the largest congregations.

German Moravian missionaries set up their first South African mission station in Genadendal in the Western Cape, and their aims immediately conflicted with the colonial authorities.

They welcomed people of all races to the church, and to live in safety in their mission stations at a time of genocide, forced evictions and displacement of people of colour by the colonial powers, and in direct opposition to the authorities’ dehumanisation of these peoples.

Almost three centuries later, the people who lived on the land, predominantly Khoi, want to control and govern the land their forefathers worked and which some have referred to as their birthright.

“The Europeans got our land with three things: with the gun, with the Bible and with alcohol,” says Naomi Julius, who was born in Goedverwacht and is now in her 60s, descending from many generations of Khoi. She farms eucalyptus on a small piece of land.

In 1810, Dutch coloniser Hendrik Schalk Burger claimed and settled, with his slaves, on the piece of land that is now Goedverwacht. The Khoi had been living and farming the area for centuries.

In his will, Burger left the land to Khoi who had worked the land and his slaves.

Rumour has it that this was because he had a romantic relationship with one of his slaves.

Goedverwacht started as a Moravian Church mission station in 1889. Residents want ownership and have also declared a dispute because they pay for services they say they don’t receive.

Goedverwacht started as a Moravian Church mission station in 1889. Residents want ownership and have also declared a dispute because they pay for services they say they don’t receive.

When the church subsequently bought the land for a meagre amount from the slaves’ descendants upon emancipation, it took away all control from the Khoi, who had been living in a self-organised manner for at least 50 years since the farmer’s death.

“Growing up, we lived freely like the Khoi did, we had horses, goats, chickens and we were completely self-sustaining,” Julius says.

“When the missionaries came and said they wanted to ‘buy the land’ from us, we were uneducated and didn’t know how to financially value the land, and we were not given any agency.

“We were indoctrinated and mentally abused by the church. They told us we were living ungodly and immoral lives. I didn’t even know that we had rights as Khoi people till I was 60.”

Goedverwacht is one example of how the church has not been holding up its part of the bargain with the government regarding land reform and the mission stations.

In 1996, land affairs minister Derek Hanekom and the Moravian Church signed the Genadendal Accord, which was an agreement of cooperation between the department and the church in South Africa, a declaration of intent to address land reform and land tenure issues at mission stations.

But there are no examples of the church aspiring to any of the actions in this document, and several examples of it reneging on them.

For example, the accord says the church should “harness and exploit … tourism and other unique income generating opportunities”.

Tourism is the subject of a lawsuit between Julius and other women in Goedverwacht, and the church.

One of the other plaintiffs, Lorraine Cornelius, explains that even though the court case centres on what was initially a specific matter — the church closing the mill, which doubled as a heritage centre and museum — it is symptomatic of the greater issue of the church not supporting what was a small but thriving tourism industry. Its remnants are two empty guesthouses.

The industry included agro-tourism, tours of Khoi rock art, garden walks, homestays and learning about Khoi and other local culture.

Julius and Cornelius are part of Goedverwacht Awakens, an organisation of women, most born in the town, some returning after years working elsewhere, who have created their own tourism attractions outside the town to benefit their community.

The best-known of these is the annual Snoek en Patat Fees on the nearby Raaswater Farm, a winter festival now in its 17th year that attracts more than 10 000 people.

“We want the property back from the church,” says Cornelius.

“We don’t necessarily want the title deeds, but this is land we inherited and we want the property to be governed by the community, for the community. It would mean we would be able to use the land, we could farm as much as we wanted, we could pick from the land without having to pay levies to a church that gives us nothing.”

Without land to farm and monetise, the residents of Goedverwacht are poor and most have to leave town for work, she says.

The taxes and rent that they pay the church are, as per the accord, meant to be used the development of the town but this has not happened.

The church owes the Bergrivier municipality R10 million in rates and taxes and the municipality has initiated legal proceedings against it.

Cornelius says people have not been drinking the tap water for five years, even though they still pay for it, because the church has not been using the government-installed water treatment plant. This is partly because Eskom has cut off the electricity supply as a result of the church owing the power utility money.

Goedverwacht’s residents carry canisters to the nearby Berg River and collect water from there.

Ferrial Adam, the director of the organisation WaterCAN, who worked with Goedverwacht’s residents in 2023, says people have been paying the church for water for years but the money is not going to the Berg River municipality as it should.

“People sometimes don’t have water for days. When we held community meetings about this, we always invited church officials and they just ignored us, didn’t even acknowledge receipt,” she says.

“These people are bullied by the church. They don’t even know if they are drinking clean water.”

Cornelius says she has sent emails to the town’s Reverend Brother Cyril Galant requesting a meeting, but received no response or acknowledgment.

“The decisions about leasing and taxes were made before my time,” Galant says. “Any issues that the community has needs to go to the Overseers’ Council.”

He added that he has not received emails from Cornelius or any other residents.

The Overseers’ Council, a conduit between the church and the residents, is a standard body in Moravian mission stations, but in Goedverwacht, many people have no faith in it and do not consider it democratically elected.

Another town deep into a lawsuit against the church is Elim, one of the larger, older and more developed mission stations. It is a three-hour drive from Cape Town and was named after a Biblical place “with twelve fountains and seventy palm trees”.

Church Street, the road entering the town, is lined with small milk-white houses with thatched roofs and walls made of mud. On the little grassy patches outside two or three older people relax on wooden chairs.

But what is not visible is that many of these houses are caving in on the inside because the church is not providing the town with maintenance services.

Elim has 49 small-scale farmers, and the church owns more than 7 000 hectares of agricultural land. Most of the farmers lease about 10 hectares each.

Elim is another town on Moravian Church land where residents have declared a dispute.

Elim is another town on Moravian Church land where residents have declared a dispute.

A life-long resident of Elim, founder of the heritage centre and one of the initiators of the legal proceedings is Amanda Cloete, who refers to herself as a “walking encyclopaedia” on the area’s history, knowing the names of every person buried in the graveyard.

“From 1758, the area on which Elim stands, including the agricultural land, was a farm called Vogelstryskraal, and birth registries show that it was all Khoi, specifically the Hessequa and Chainouqua peoples, who lived here,” says Cloete.

Until 1825, all the houses were mud huts and it was only when the church arrived that people were forced into a rental system.

“It is our Khoi history that will win this case,” Cloete says confidently.

Here, unlike in Goedverwacht, the Overseers’ Council and residents have a good relationship. Residents pay rent to the church for farmland, but pay levies to the Overseers Council, which has had to take on the responsibility for providing essential services that, according to the Genadendal Accord, should be provided by the church.

The council has ensured the town has stormwater drainage, good roads and infrastructure, and even streetlights. When the church began hostile legal proceedings against the council for a relatively smaller matter, it unwittingly opened the door to a greater battle over land ownership and control.

Beresford Pearce, a member of the Overseers’ Council, says an amendment to the official ownership of the land on which Elim stands will change everything for the town.

“We will be able to govern the town with money currently going from farmers to the church coming back into the community instead. We could develop infrastructure, create jobs and would have investors who now stay away because we are ‘owned’ by the church. Right now we are living month to month,” he says.

Pearce says the church sabotages any financial ventures by the residents, such as harvesting wild flowers and pine trees.

And because people have to pay it for agricultural land, very little farming that could be monetised is taking place.

Beresford Pearce believes a change in ownership will see the town flourish.

Beresford Pearce believes a change in ownership will see the town flourish.

Brigitta Mangale is the director of the pro bono and human rights practice at Cliffe Dekker Hofmeyr, and the primary attorney on the case. She says there are a number of pending matters regarding Elim, but ultimately the main relief has to do with ownership, and that the court finds that Elim residents are the rightful owners of the land from before the time of German settlers and put in place a declarator saying that.

“The only reason we are in this legal mess is because the Moravian Church settled on the land at a time when people of colour couldn’t own land, and it was in its settling that it came to hold ownership in the first place,” Mangale says.

The lawsuit is a tricky one because it is partly based on customary law and, as with so many people of colour in South Africa, the history was not documented.

The legal team will rely on the expert testimonies, historians and the elders of Elim.

“We are trying to rectify and bring into the current day the terms of a custom that was in place for centuries before the colonial apartheid system changed this — a custom where the land belonged to the people, where everything that came from it was supposed to be shared and flowed back into the community.”

Elim is an example of a general issue with the implementation of the Genadendal Accord, Mangale says.

From the signing of the accord, the government had all sorts of planned programmes for land reform of church missions stations, and touts towns such as Pella in the Northern Cape as successes. But the people there are still as poor as ever and have seen no development.

She says the accord in itself has not been useful in protecting indigenous people.

Wilmien Wicomb, an attorney and the lead of the land programme at the Legal Resources Centre, says: “The Genadendal Accord’s principal intention was to provide security of tenure, that is, secure land rights to the inhabitants of the church land.

“But the accord is not specific as to how the land rights should be secured because, at the time, there was an assumption that as part of our constitutional transformation, our property system — which was entirely based on the inherited Roman Dutch property system based on ownership — would be reformed to reflect the many different ways in which people hold land rights in South Africa.”

The apartheid system that prohibited most South Africans from owning land created peculiar land rights. Acknowledging these, plus customary and indigenous forms of land rights, communal, household and individual land rights, the accord wanted to leave space for church communities to define their own preferred property regimes.

In Elim, being born in the town is not enough to be a “citizen” — it is a privilege obtained only after taking citizenship classes.

From the age of 16, the children of Elim and adults from elsewhere are required to apply for citizenship. This training takes place annually and during the process the Overseers’ Council and Church Council teach candidates the rules of the mission station as contained in its rule book, or “ordinances”. After completing the training they are sworn in during a church service as new citizens.

Members of other Moravian congregations may apply but will be carefully selected and have to show an ancestral link to Elim, and are required to be what the church considers “good standing members of the Moravian Church”.

Ultimately, this means that only someone belonging to the Moravian Church is allowed to live in Elim — or in any Moravian mission station for that matter.

This raises the question of the legality of this practice, because both the Constitution and the Rental Housing Act do not allow for property owners to discriminate against people based on religion.

And just as with the issue of land rights, this could be quite a complicated matter. Furthermore, research on this topic is not easily available.

Tanveer Jeewa, a constitutional law lecturer at Stellenbosch University, says: “We need to ask the question: if the church only leases its land to people who are members, is that discrimination or mere differentiation?”

She says one could argue that just as with any other private organisation, it is generally permissible to give preferential treatment to people who belong to it.

In the same vein, being a member of the Moravian Church is a condition that, as a private property owner, it is entitled to impose for leasing purposes.

But what about the Constitution prohibiting discrimination on religious grounds? This is not as straightforward as it would initially seem.

“The question becomes: does membership of the Moravian Church amount to a religious requirement, or is it an organisational preference?” says Jeewa.

She explains that because the Moravian Church is a denomination within Christianity and does not hold beliefs that are fundamentally distinct from other Christian denominations, requiring membership of the church to lease land may be legally differentiation, as opposed to discrimination.

“In South Africa, courts have generally shown deference to both private property rights and the autonomy of religious institutions in managing their internal affairs. That tendency may also influence how the courts approach this question,” Jeewa says.

Lizwi Mtumtum, the president of the Moravian Church in South Africa, did not respond to the Mail & Guardian’s questions, saying the church does not usually deal with the media.

“I also wonder how you came about doing this investigation. Put differently, on whose bidding are you raising these questions?”

“Nonetheless, as your questions are of a legalistic nature, I need to refer same to our legal team, especially since we have a court case with regards to Elim on this very matter,” he says.

The cases against the Moravian Church are certainly not simple, but are crucial in the move towards real land reform.

The courts will have to address not only the issue of customary land rights, but also decide who the accords and laws are meant to protect — the descendants of indigenous people, organised religious institutions or slave-era colonising landowners.

“Our forefathers brought this land to what it is, but this church is greedy and sees it as a business,” says Cloete.

“If we win this case, we win for the people of all Moravian mission stations in South Africa.”

This investigation was supported by the Sylvester Stein Fellowship Fund, awarded to the journalist by the Canon Collins Trust.