Artist and photographer Thembi Mthembu pictured at the Gulf of Venice in 2019. (Thembi Mthembu)

A nude woman sits on a chair along the Gulf of Venice. Tourists and locals blur in the background, seemingly unperturbed by the person in focus, who meets the camera’s gaze. There is a thin, black line drawn over the waves, a small detail in the grayscale photograph.

In another colour image a different woman bathes in the waters of Arles, about 800km away. The woman’s features are unidentifiable, but the mauve water surrounding her is translucent and has calm ripples. The former portrait is by the KwaZulu-Natal artist and photographer, Thembi Mthembu, taken in 2019 during a trip to the Biennale. The latter is a self-portrait of documentary photographer Mandisa Buthelezi, taken during her 2016 Studio Vortex residency in France.

In Izithunzi Zami, Mandisa Buthelezi shifts her introspection to herself through portraits of her body. (Mandisa Buthelezi)

In Izithunzi Zami, Mandisa Buthelezi shifts her introspection to herself through portraits of her body. (Mandisa Buthelezi)

Mthembu and Buthelezi are part of the zeitgeist of young South Africans re-imagining photography. Both represent the importance of telling one’s story. Though their images are informed by different experiences and have different intentions, their work illustrates the role of self-portraiture in creating new narratives and decolonising the photographic medium.

Their journeys and choices in self-portraiture and visual storytelling have been important in establishing new narratives about the Southern African landscape and shaping contemporary visual archives.

A brief history of South Africa’s relationship with portraiture

An image from Mandisa Buthelezi’s uBhuku lukaMenzi series, which revisists the story of princess Mkabayi kaJama (Mandisa Buthelezi)

An image from Mandisa Buthelezi’s uBhuku lukaMenzi series, which revisists the story of princess Mkabayi kaJama (Mandisa Buthelezi)

South Africa’s photographic history is rooted in colonial, anthropological portraiture. In the 1800s, the camera was brought to the coast of Durban, as colonisers set up studios to take portraits of settler families, and to photograph indigenes — whose names were often not recorded — for studies. Later on in the 1950s, portraits were used as identifiers for identity documents or dompases. In this way, early uses of photography were inherently classist and oppressive.

The accessibility of photography enabled more people to partake in the practice. During the 1980s, there was a rise in photography as a tool for activism. Collectives and independent photographers began to document their own stories. Examples include the social documentary and resistance photography collective Afrapix, as well as Santu Mofokeng and David Goldblatt, who used photography to record everyday life under apartheid. These archives can be seen as attempts to decolonise the photographic practice, because they contributed nuanced depictions of the society of which they were a part.

Photography as celebrating the self and reflecting the times

After making portraits for fun, Thembi Mthembu realised the dynamism of making meaning and began to add narrative to the nudes. (Thembi Mthembu)

After making portraits for fun, Thembi Mthembu realised the dynamism of making meaning and began to add narrative to the nudes. (Thembi Mthembu)

Mthembu grew up in Enseleni, Richards Bay. Her interest in photography began after watching a TV interview during the 2010 Fifa World Cup. “There was this lady, a sports photographer. She was talking about her career and how vast photography was as a career. That’s when I gained my interest in photography,” she says.

Mthembu studied photography at the Durban University of Technology by doing a foundation course for one year and gaining an array of visual art skills. In her third year, she began exploring nude photography. “I wanted to do something different from the rest of the class. [Nudes] were trending at the time on Instagram.”

For the artist, photography became a way of exploring her androgyny. (Thembi Mthembu)

For the artist, photography became a way of exploring her androgyny. (Thembi Mthembu)

It was 2015 when she made the portraits for fun, but on reflection, Mthembu realised the dynamism of making meaning and began to add narrative to the nudes.

She attributes her desire to share her journey of embracing her body to her formative experiences. “I have a twin sister. We’re fraternal and she is more feminine looking than me, so I was different and I was often compared to her, which led to low self-esteem. [Self-portraiture] became a platform of expression — me discovering and embracing my imperfections.”

Mthembu says photography became a way of exploring her androgynous features to make sense of her identity on her own terms. “It made me revisit my childhood traumas that I never paid attention to. The minute I started posting and talking about my experiences, then I would get people relating to my story.”

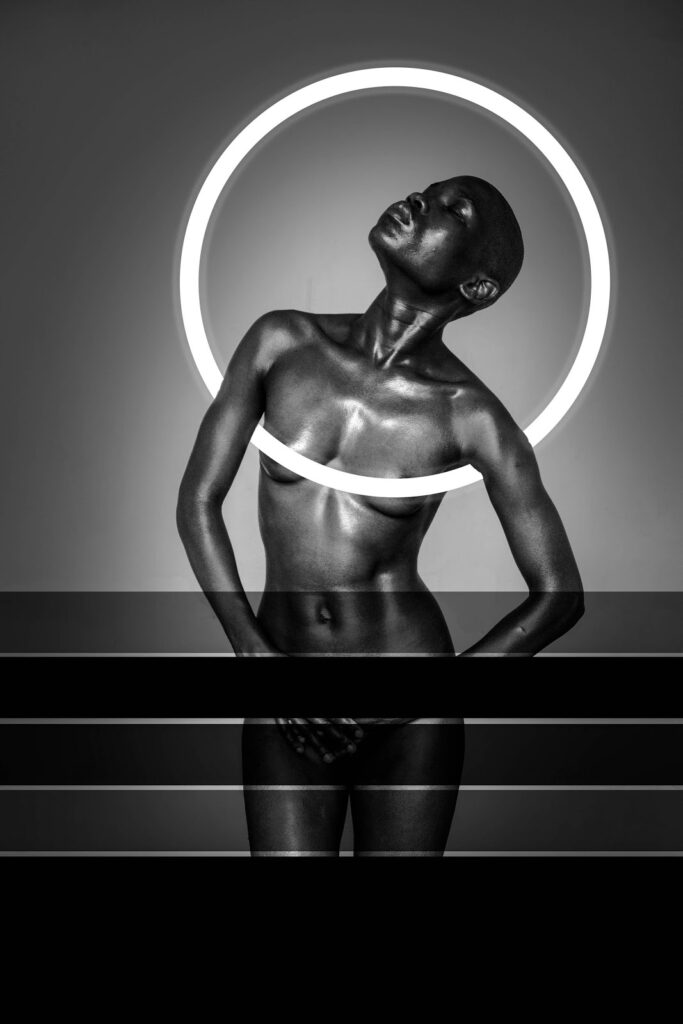

Mthembu adds elements of digital design to step away from traditional documentary self-portraiture. (Thembi Mthembu)

Mthembu adds elements of digital design to step away from traditional documentary self-portraiture. (Thembi Mthembu)

The main focus of her work is her body, but she adds elements of digital design to step away from traditional documentary self-portraiture and subtly present ideas about body politics, freedom and technology. “In order for the next generation to see what was happening now, they have to see our work, so they know we lived in the introduction of technology and digital manipulation.”

Narratives as a way of elevating history and selfhood

The photographs in uBhuku lukaMenzi are new ways of approaching documentary photos, where a narrative from another time is introduced (Mandisa Buthelezi)

The photographs in uBhuku lukaMenzi are new ways of approaching documentary photos, where a narrative from another time is introduced (Mandisa Buthelezi)

Mandisa Buthelezi uses her photography to explore her cultural heritage and to affirm her identity. Her recent series, uBhuku lukaMenzi, revisits the story of Princess Mkabayi kaJama, Shaka’s aunt who was dismissed for presenting herself as a strong woman. “I was really taken by the fact that she had so much power as a royal woman of the Zulu monarchy,” says Buthelezi. “She was in the centre of politics to such an extent that she appointed herself as regent of the throne because her brother, King Senzangakhona [Shaka’s father) was too young to take over.”

The photos in uBhuku lukaMenzi are new ways of approaching documentary photos, where a narrative from another time is introduced. The photographs are black and white and graded with a granular texture. The series translates as a visual story, with pieces of the Princess Mkabayi allegory. For instance, in one image there is a calm setting in which women are doing each other’s hair. Juxtaposing this is a more frenetic image of dancing feet and rising dust. If we are to connect the images to the story of the princess, they can be read as moments of community followed by uprising in Mkabayi’s life.

Juxtaposing calm and frenetic settings, the images can be read as moments of community followed by uprising in Mkabayi’s life. (Mandisa Buthelezi)

Juxtaposing calm and frenetic settings, the images can be read as moments of community followed by uprising in Mkabayi’s life. (Mandisa Buthelezi)

The story Buthelezi presents through research and personal connection to Zulu culture is reminiscent of a historical document. Through her use of captions we are aware that Buthelezi has intentionally created this grand visual pairing for a story that is more than 100 years old. “The conversation I intended to initiate with the work, over and above celebrating Princess Mkabayi, is to relook at how women of power have been represented through historical texts and narratives. Everyone knows that the game of politics/power is a kill or be killed game. When men participate and win, they are celebrated but when women take part, they are vilified.”

Looking at the series as a whole, we can understand the story of Princess Mkabayi because it reads like an unconventional photostory. Buthelezi informs our knowledge of the tale through her commentary.

In her other work, Izithunzi Zami, Buthelezi shifts her introspection to herself through portraits of her body. “Izithunzi Zami was a very intimate and internal body of work, and it is a project that really challenged me to interrogate the connection I had with myself, the environment, as well as the relationship I had with what I was going through at that particular time.”

The images are strong stand-alones and the vulnerability offered to the viewer is palpable. “It was also extremely spiritual and taught me a lot about my creative process and practice, and this shifted my photography discipline since.”

The work is emotive because she made the portraits herself and reveals something earnestly beautiful, without the gaze of someone else.

Past and present storytelling

Contemporary photography offers the opportunity to re-frame and re-present our stories.

Mthembu and Buthelezi’s work collectively contributes to shaping current visual narratives through referencing the past, as seen with Buthelezi’s work. uBhuku lukaMenzi revisits a historical narrative, while her self-portraiture explores her identity. Mthembu uses self-portraiture to revisit her experiences as a child, while using visual cues to present her current life in a technologically-informed era.

Much like Goldblatt, Mofokeng and other photographers who have contributed to the current archive, and contemporaries such as Zanele Muholi, a formidable figure in documenting the self, Buthelezi and Mthembu are contributing to a living archive of documentary self-portraiture.

This article was produced as part of a partnership between the Mail & Guardian and the Goethe-Institut, which focuses on innovation in various aspects.