Donald Goines

Hustler narratives have emerged as a genre in world literature since the mid-1960s. It is an expansive genre, but deals broadly with the shortcomings of any given political economy as seen from the perspective of characters who position themselves as both victims and villains.

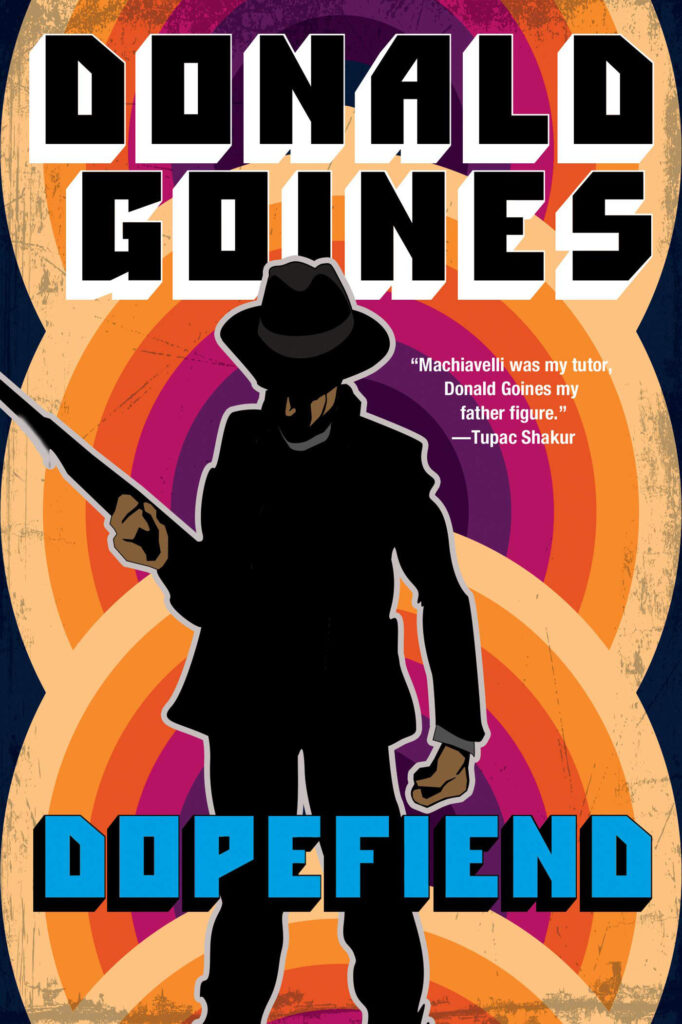

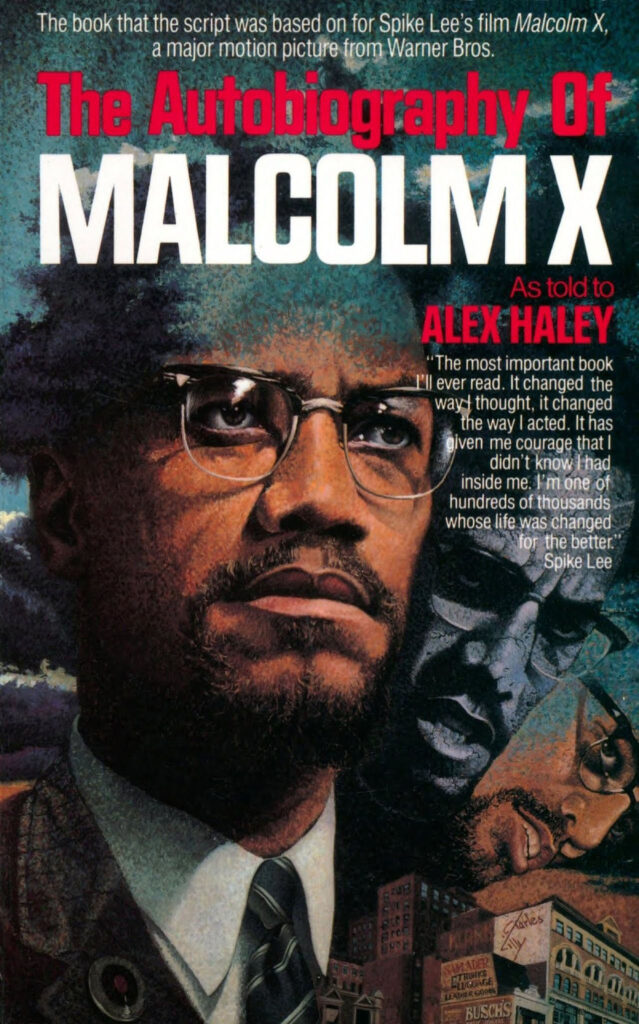

There have been groundbreaking hustler narratives from the US — like The Autobiography of Malcolm X (1965) written by Malcolm X and Alex Haley, and Donald Goines’s Dopefiend (1971). In recent times, critics have described the work of African American writers in this field as a type of crime fiction. They carry the expressions of people’s response to inner city problems such as de-industrialisation and police repression. The books represent individuals who operate outside the bounds of what US society might consider acceptable, just to survive.

Seminal: Dopefield, written by Donald Goines, is an early example of the hustler narrative

Seminal: Dopefield, written by Donald Goines, is an early example of the hustler narrative

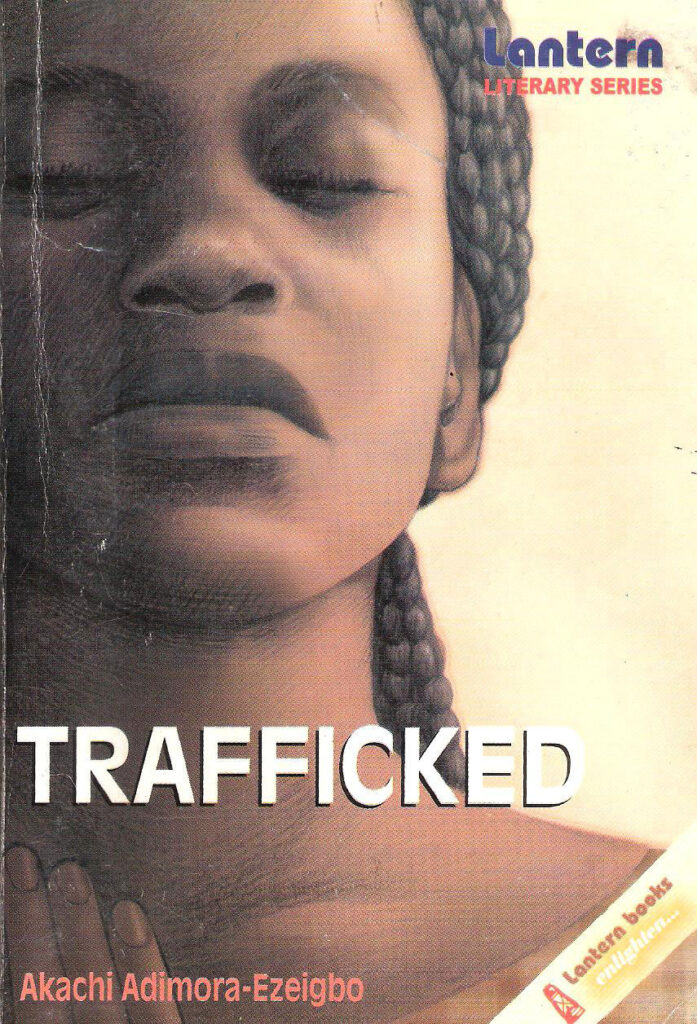

Nigeria has made its own contribution to this field with its stories of political and religious hustle, sex worker narratives and many others about roadside hawkers, destitution, petty theft and internet fraud. Notable examples include Akachi Adimora-Ezeigbo’s Trafficked (2008) and Igoni Barrett’s Blackass (2016). Other African entries include South African novelist Niq Mhlongo’s Dog Eat Dog (2004) and Congolese author Alain Mabanckou’s Black Moses (2017).

Akachi Adimora-Ezeigbo’s Trafficked (2008)

Akachi Adimora-Ezeigbo’s Trafficked (2008)

African hustler narratives represent the way people survive at the margins of postcolonial African economies. A distinct kind of African hustler narrative is the Nigerian e-fraud story, portraying characters who engage in cybercrime trying to make scam email recipients part with their money — locally called “Yahoo Boys”. The narratives show how people attempt to overcome geographic and economic disadvantages by creating alternative networks.

In a recent paper, I analysed some of these e-fraud novels — and one in particular, I Do Not Come To You By Chance by Adaobi Tricia Nwaubani — to show that they fit the literary canon of hustler novels and to find out what they have to say as a critique of the Nigerian state and its economy.

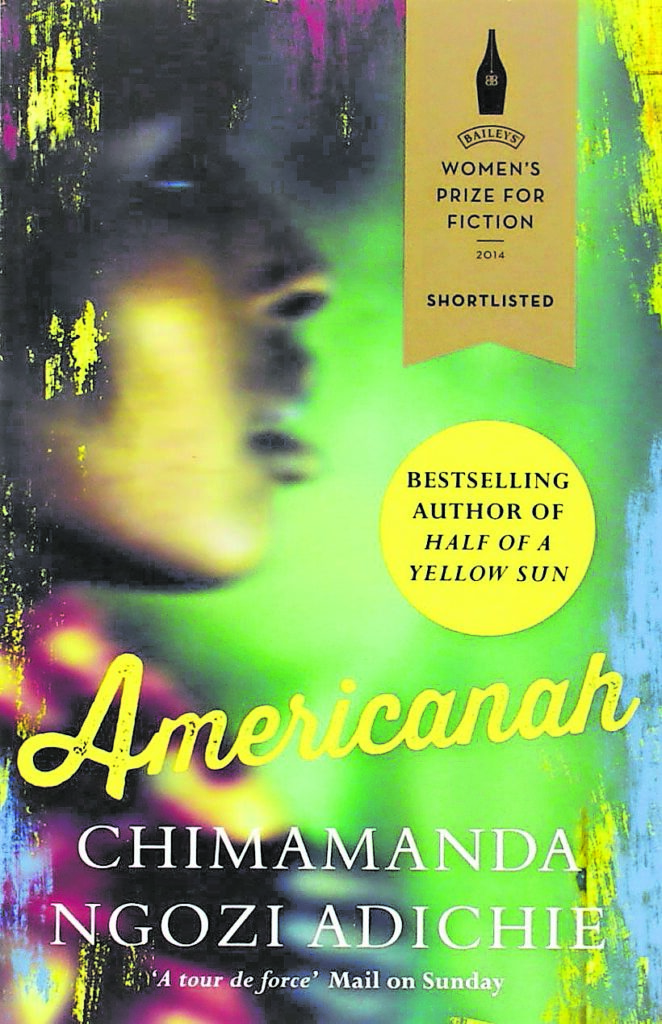

Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie’s Americanah

Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie’s Americanah

Between Afropolitans and hustlers

In my study, I looked at Nigerian hustler narratives in relation to another common trend in African literature today: Afropolitanism.

Afropolitanism describes the experience of African subjects who attain the status of global citizenship. They do this by connecting to other non-African expressions of identity, community and sense of belonging.

Both hustler and Afropolitan narratives highlight the possibility of migration as a way to move socially. But whereas the privileged Afropolitan has a real chance of migration, the African hustler can access it only through a backdoor channel.

For example, In Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie’s Americanah, Ifemelu’s migration to the US is through a legally documented process. In contrast, the female hustlers in Chika Unigwe’s On Black Sisters’ Street pay a pimp to smuggle them from Lagos to Antwerp.

However, instead of physical migration, the hustlers (e-scammers) in Nwaubani’s I Do Not Come to You by Chance resist poor economic conditions by creating an alternate digital universe. This they navigate by email, for access to global locations of capital.

Nigerian hustler narratives establish e-fraud practice as an alternative economy and show how and why such economies emerge. They can also be a potent critique of young Nigerians’ exclusion from the postcolonial economy.

There have been groundbreaking hustler narratives from the US — like The Autobiography of Malcolm X (1965) written by Malcolm X and Alex Haley

There have been groundbreaking hustler narratives from the US — like The Autobiography of Malcolm X (1965) written by Malcolm X and Alex Haley‘I Do Not Come to You by Chance’

The protagonist of Nwaubani’s book, Kingsley, turns to e-fraud as a way out of poverty.

After independence in 1960, Nigeria continued to adopt the colonial model of an extractive economy, with its dependence on crude oil. After the fall in global oil prices in the 1980s, Nigeria adopted a neoliberal economic policy called a structural adjustment programme. But this failed to improve the lives of ordinary citizens and encouraged them to engage in capitalist pursuits.

Kingsley yearns to perform the traditional duties of a family’s opara (firstborn son), which include taking care of his siblings and widowed mother. He applies for work at Nigerian oil companies but none employs him. So he joins his uncle, Cash Daddy, in the informal economy of online fraud. He declares: “I was not a criminal. I had gone into [internet fraud] so that my mother could live in comfort and my siblings have a good education.”

E-fraud and the Nigerian state

But in embracing e-fraud as an alternative to his economic exclusion, Kingsley recreates the same exploitative economic landscape that he seeks to avoid.

In one of his scam letters, he exploits the decadent image of Nigeria’s political economy and positions himself within it as a victim. He pretends to be the widow of former Nigerian head of state, General Sani Abacha, describing the persecution of the widow’s household following his death: “I have been thrown into a state of utter confusion, frustration and hopelessness by the current civilian administration. I have been subjected to physical and psychological torture by security agents in the country …”

What Kingsley has done is to weave his personal experience of economic deprivation into a scam email. Terms like “hopelessness” and “psychological torture” serve to appeal to the scam target’s pity and earn their trust. But they simultaneously hold true about Nigeria’s economic uncertainties and Kingsley’s economic vulnerability. In this way, readers are introduced to the degenerate world of Nigeria’s postcolonial economy, one that emasculates the postcolonial subject.

Kingsley’s story forms a critique of the Nigerian economic culture in which he is allowed first to starve and then to prosper.

This is an edited version of an article first published in The Conversation.