Ravelle Pillay – Studio Portrait

The painting department felt like a secret society when I was at Art School, a sorority bound by terms like “scumbling”. Their studios were on the upper floors of one of the older buildings on the campus, whose tall doors creaked and shuddered in the wind. Their work seemed more enigmatic than anything the printmakers or sculptors were conjuring up. Walking into that turpentine-soaked air and gazing into the depths of their drenched, dripping and scrubbed canvases made me feel I was missing something – missing information and missing out.

Guided in part by artist and lecturer Virginia MacKenny, these painters worked with washes, layering and other complex processes of adding and removing that have been popularised by artists like Peter Doig, Marlene Dumas, Kate Gottgens and, more recently, Ruby Swinney (to draw a rough sample from a large pool).

Though a feeling of alienation still haunts my experiences with contemporary painting in this mode, I have learnt that layering, ghosts and missing information are a significant part of what draws both painters and audiences to it. I believe this is because it resonates with our shifty relationship with time and memory. Complex formal layering enables the unravelling and re-ravelling of layered and complex narratives. What this way of painting lacks in humour, it makes up for in depth.

It is with all this in mind that I engage with Tide and Seed, Ravelle Pillay’s first exhibition with the Goodman Gallery in Johannesburg. For Pillay, painting “has the ability to reveal or hide, morph or strip down, in ways that transform the reference”. Her references are drawn from personal and historical photographic archives. She uses these photographs as a base for a material investigation into her ancestry and family history in the former British colony of Natal, as part of a broader narrative of Indian indenture across colonial strongholds.

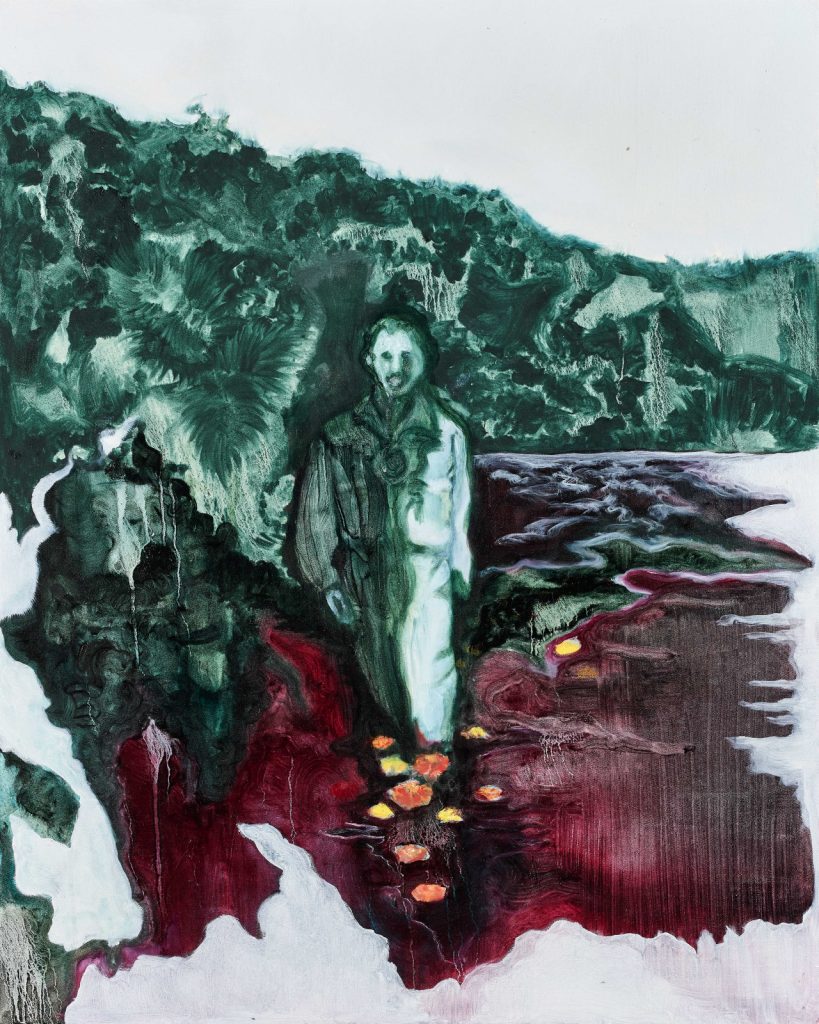

Ravelle Pillay, Stranger, 2022, Oil on canvas. (Anthea Pokroy)

Ravelle Pillay, Stranger, 2022, Oil on canvas. (Anthea Pokroy)

The paintings on this exhibition comprise heavy, lush foliage and swampy waters that threaten to overwhelm ghostly figures lodged in photographic poses. Where the landscape and vegetation are inky, bloody, textured and deeply embedded, the figures seem to be fading, wearing or washing away.

Pillay is curious about the ways in which the natural world is co-opted in and serves as a witness to violence and oppression – how banana trees and sugarcane thrive along with legacies of slavery and colonialism. During a public discussion at the gallery, she described her interest in the bones that washed up in people’s yards, exhumed by the recent devastating floods in KwaZulu-Natal. She goes on to expand on how paint is deployed as a kind of sediment or residue on the canvas.

Pillay’s figures are mostly faceless, with features occasionally hinted at. This is recognisable in the work of several contemporary painters, especially those who work with existing photographs. A colleague of mine recently asked, “How much of an artist’s determination to leave out faces and hands is due to their inability to paint them?” Anyone who has ever tried knows the challenge presented by faces and hands. My feeling is that in most cases, the decision to dodge these elements has a corollary in the conceptual underpinnings of the work.

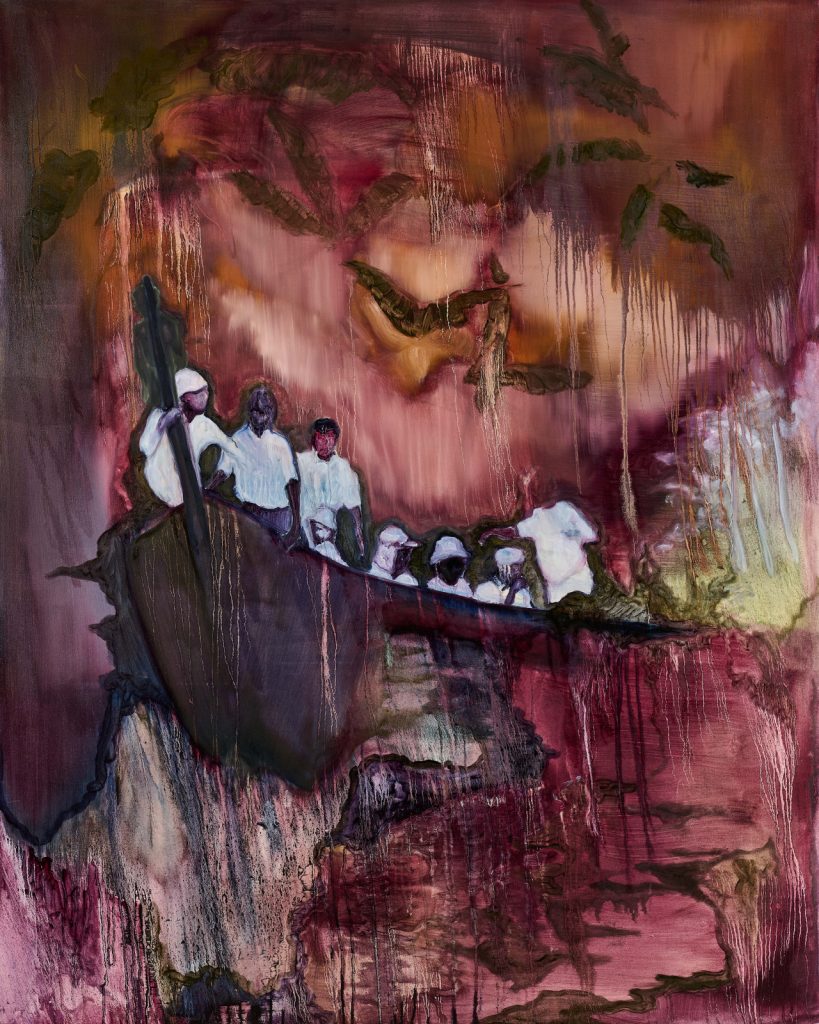

Ravelle Pillay, Crossing, 2022, Oil on canvas. (Anthea Pokroy)

Ravelle Pillay, Crossing, 2022, Oil on canvas. (Anthea Pokroy)The faceless and, even sometimes headless, figures in the precise paintings of Matty Monethi are rendered very differently to those in Pillay’s work but are also drawn from photographic references and used to explore themes of migration and memory. Monethi is a contemporary artist from Maseru, Lesotho, who described the decision as follows: “When I started working in the way that I do now, my family were my subjects. It was a very personal body of work and I was hesitant to give too much away, so I withheld their faces.

“I believe our face is only a small part of who we are. As time passes, more reasons have developed for the faceless subjects. It’s become a way for me to represent gaps in memory, those absences that emerge in the act of remembering.”

Pillay’s figures are in part representatives of a collective history. She explains how the anonymity of her subjects “… leaves space for projection and takes a little pressure off the figure to do all the work in the painting”. This allows other elements to come to the fore. The archival images she works with are also often very degraded, with the features hard to discern.

Pillay is clear about not wanting to represent a particular time or place in her work. The reference material is a starting point. Painting allows for the picturing of “another, fictional place” outside of past and present time. On several occasions, Pillay reiterates that, “the point is painting”. She explains, “Painting is not just a ‘lens’ or a means to a conceptual or other end, painting itself is the point of the making.”

Of course, her references are also markers of personal celebrations, loss, familial ties, natural disasters and violent histories, the detail of which has been wilfully erased by successive inhumane administrations and by the inevitability of time. These subjects and their “bones” are at the mercy both of those administrations and those who choose to archive, paint and exhibit them. Pillay considers herself a custodian of the archives she works with – but painting is the point.

Ravelle Pillay, Avalon (The Undertow), 2022, Oil on canvas. (Anthea Pokroy)

Ravelle Pillay, Avalon (The Undertow), 2022, Oil on canvas. (Anthea Pokroy)Pillay’s career looks to be moving quickly, although she has done her time on the clerical side of the industry, previously working as an assistant for another artist and for an auction house. When asked how she feels about her recent recognition and acclaim, she expresses her gratitude at finding herself able to spend all her time painting. “It feels like a lot, but it is also something I’ve been waiting for.”

Pillay will be in residence at the Gasworks in London towards the end of this year, leading up to her first institutional solo show at Chisenhale Gallery in the city in February. This intensive time of making and showing might push the artist to find her own voice within an established language of painting, sharpen the focus of her work’s conceptual basis and help bring these two elements closer together.

Tide and Seed by Ravelle Pillay is on exhibition at Goodman Gallery until 30 September. Address: 163 Jan Smuts Avenue, Parkwood.