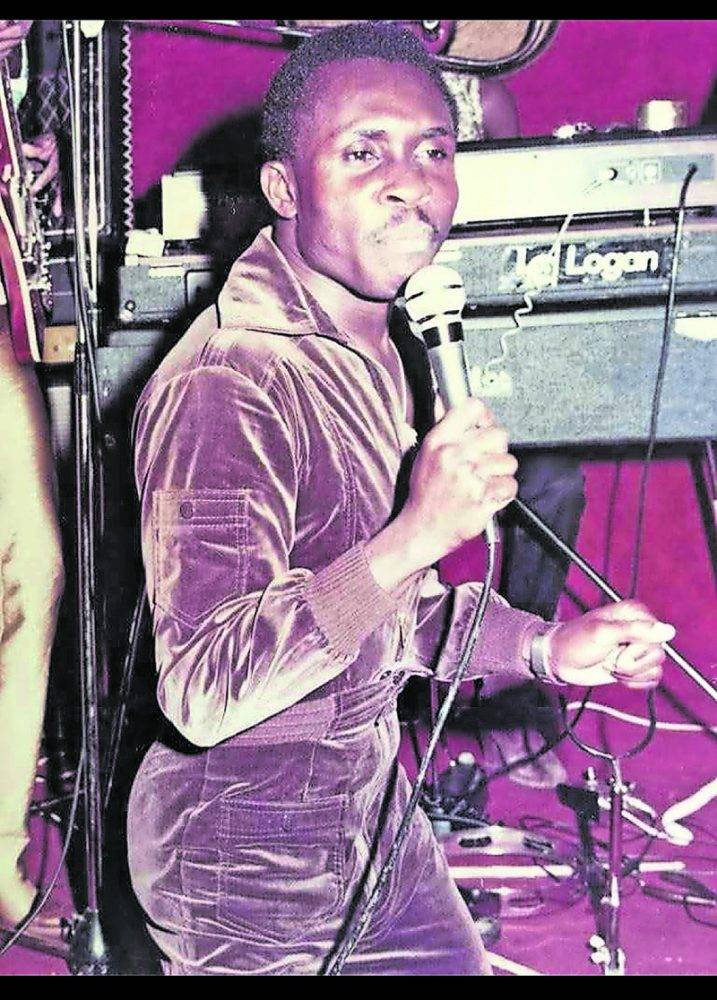

Pat Thomas is one of the the Ghanaian highlife musicians who moved to Europe.

Highlife is the “soul” of Ghana. More than just a sound, highlife is an institution that provides an anthology of Ghanaian nationhood.

A blend of African rhythms, jazzy horns, lilting guitar licks, social commentary and folkloric lyrics, the music proudly projected African identity in a time of rapid modernisation and post-colonialism.

In the 1960s and 1970s, across Ghana, highlife ruled the dance floors of a thriving live music scene.

“In our time, you had to be really good to be a member of a band. It was very competitive,” recalls Andy Vans, a veteran highlife pioneer who got his start in music playing under the legendary bandleader Ebo Taylor.

“And Ghana was the place to be. All the great African musicians were flocking to Ghana.”

In what is wistfully remembered as “the golden age of highlife”, bands packed dance halls and bars across the country. It was a time when music had the power to deliver wisdom, comment on social issues and often effect political change.

However, the late 1970s would see the decline of the popular live music scene due to the incoming military regime, a devastating economic crisis, and the rise of a new sound in popular music.

Economic hardship and social restrictions aside, changing tastes turned down the volume on the live music circuit. Imported disco music and DJ culture became the new craze. This was partly due to the popularity of films like 1977’s Saturday Night Fever, as well as a flood of American records with high production values.

The emergence of DJs, promoters and their mobile sound systems delivered a blow from which the old dance halls never truly recovered. There were fewer and fewer jobs for musicians and, within a few years, the vast majority of them had either migrated abroad or hung up their instruments.

By the start of the 1980s, a new form of highlife music punctuated Ghana’s airwaves. It was a style defined by a burgeoning Ghanaian diaspora across Europe and North America that used new technology and recording techniques.

The heart of this scene was Germany, which was a preferred destination, partly due to the flexible immigration policy at the time. Those at the centre of this new community became known as “burgers”, derived from the German word for citizens of Hamburg, a hotspot for Ghanaian migration.

This generation of émigrés included many of the country’s foremost musicians who were inspired to remake the irresistible rhythms of highlife out of their own social and cultural experience, incubating a uniquely global strain dubbed burger highlife.

As a movement that is shaped by the scattering and migration of Ghanaian people, burger highlife is difficult to pin down with a firm definition. But there are some essential coordinates: the circulation and metamorphosis of highlife and layers of diasporic musical exchange. Records that were cut in cities across Europe and North America where Ghanaians had settled pushed the envelope.

After emerging as a drummer in highlife bands in Ghana, Charles Amoah moved to Germany in 1979, where he found his place in a burgeoning Ghanaian music scene absorbing new influences and beaming back re-imagined sounds of home.

“The whole idea was to cut through, not make music solely for Ghanaians, but it was designed to cross borders, for people in Europe to relate to it too,” Amoah says.

Charles Amoah

Charles Amoah

For Pat Thomas, in 1983 that meant contorting his raw-edged singing into a James Brown-like croon over a winding highlife and Afrobeat composition.

While Gye Wani — Twi for “enjoy yourself” — doesn’t quite plant both feet in non-African styles — it sounds most fresh in the moments that Thomas can be heard pushing the mic to distortion.

As the decade progressed, the musicians of the diaspora would colour more and more outside the lines of traditional highlife.

On Fre Me (Call Me), a track originally released in 1985, Amoah reinvents highlife as a more limber, light-footed serenade. The arrangement deftly nicks Latin piano progressions and multi-percussion, and uses a bass synthesiser in lieu of a typical walking bass line, to give the instrumental a deep club sound, evoking the familiar appeal of funk and R&B.

Fre Me was recorded at Studio Wahn in Bochum, Germany, over several months with a team of fellow Ghanaian innovators such as George Darko and Bob Fiscian, playing with German session musicians.

The music scene in the diaspora was small enough that many musicians knew each other, played together and developed new takes on highlife into a unified sound alongside one another.

Amoah speaks of hours spent brainstorming the right way to play a single note.

For many artists, studio sessions with foreign collaborators abroad provided a valuable litmus test of what would become ear candy to foreign audiences.

“For the [German musicians and engineers] to be able to play the highlife, the structure of the song had to relate to what they already knew,” Amoah notes.

No sound seemed out of bounds for the experimental recordings that were being concocted.

Throughout the 1980s, Ghanaian musicians continued to produce innovative hybrids abroad, where they were less confined by genre than back home.

Their proximity to the developments in state-of-the-art music technology, and a place within a wider African diaspora, gave highlife music an endless mutability.

Tracks like Ernest Honny’s New Dance (recorded in Benin) and Nan Mayen’s moody Mumude (recorded in Germany) emulated the slickness and groove of the era, overhauling traditional arrangements, while Adjoa Amisa, Vans’ 1987 cut, re-imagined an Ebo Taylor-written original song by splurging on rolling instrumental breaks reminiscent of Congolese music.

Was their music funk, soul, pop or something else? It was all and none of those things but mostly it was still accepted as highlife.

In effect, the music was meant to cross cultural border lines. Aside from sonic innovation, the evolution reflected shifting messages.

The genre’s proponents started to look away from the heavy allegorical and politically conscious themes of much of classic highlife. Musicians instead turned to creating songs with universal appeal — sometimes at the cost of their homegrown audience.

Andy Vans

Andy Vans

Twi proverbs in song lyrics were replaced with less culturally specific references. Burger highlife’s most enduring tracks and later superstars such as Daddy Lumba, Ofori Amponsah and Kojo Antwi all benefited from this shift in writing.

In the beginning, however, while these new iterations of the highlife genre exploded in the diaspora, records struggled to win the approval of audiences in Ghana.

Purists deemed them less authentic than the classic highlife of the past and, for the masses who embraced and popularised the sound of the future, the challenge was to stand out. More than ever, it was important to make a record that would catch on back home.

If this funky highlife was going to be successful, artists had to create something much more enduring than hits. For many artists, forging this futuristic African pop music was purely a creative pursuit, at odds with the realities and struggles of being a first-generation immigrant.

“Many didn’t see the fruits of their labour. I had to stop music; I had no choice,” shares Vans, who stepped away from music for a career in IT after emigrating to Switzerland.

In 1987, he briefly came back to release the album Beautiful Collection, a quintessentially burger record in its boldness. For Vans, who inhabited a world outside the diaspora’s artistic bubble, highlife remained at the heart of his imagination.

A mixed bag by definition, the musicians of the diaspora went to great lengths to keep Ghanaian music alive, infusing their own experiences with life abroad into the music. And once again, highlife became part of Ghanaian identity.

The evolution of highlife opened the floodgates for a future of Ghanaian music steeped in fusion — and continues to exert massive influence on African pop music today.

This fleeting and unique microcosm of Ghanaian music ultimately gave way to new hybrids such as hiplife (a fusion of highlife and hip-hop popularised in the early 2000s) and contemporary Ghanaian Afrobeats further down the line.

When highlife was forged far away from home, musicians were certainly plugged into the world but they maintained Ghana’s soul as the defining rhythmic pulse of their output. These burger highlife records chronicling a decade of creative substance and innovation will keep this moment in history alive forever.

• This is an edited version of an essay by Ghanaian writer Sarah Osei that forms part of the sleeve notes of Ghana Special 2: Electronic Highlife & Afro Sounds in the Diaspora, 1980-93 (Soundway Records) (see inset picture, left).

• Three generations of Ghanaian musicians, including Pat Thomas, Charles Amoah and KOG, will perform in a supergroup at the Womad Festival in the UK on 27 July.