At the age of 28, Lerato Bereng was a shareholder and partner at the Stevenson gallery

Art galleries have always felt like sanctuaries to me — a place to lose yourself in someone else’s imagination while discovering something new about your own.

One of the joys of living in Rosebank, Johannesburg, is the proximity to a rich constellation of galleries: the Keyes Art Mile, home to Everard Read, Circa and Origins; the historic Goodman Gallery; David Krut Projects and its adjoining Art Bookshop on Jan Smuts Avenue and, just beyond, in Parktown North, the likes of Momo, Stevenson and Kalashnikovv.

Yet, despite this abundance, few of these galleries are owned by young black people. For too long, the art world has been seen as the domain of old white money — a perception that isn’t unfounded.

When I first moved to South Africa, nearly a decade ago, I noticed this divide acutely. I’d invite friends to exhibition openings, only to be met with polite but firm refusals.

They didn’t feel welcome in those spaces and who could blame them?

Galleries often seemed like fortified enclaves, more about exclusivity than inclusion. But I have noticed a shift over the years — a slow, yet significant, reimagining of who gets to own, create and curate in this world.

My favourite gem on the Keyes Art Mile is BKhz, founded by multi-disciplinary artist and curator Banele Khoza when he was just 24.

Khoza was inspired by a transformative trip to Paris in 2018, where he completed a three-month artist’s residency at Cité Internationale des Arts, after winning the prestigious Gerard Sekoto Award.

Walking through the historic Le Marais district, Banele was struck by a modest 40m2 gallery thriving in one of the most expensive parts of the city.

“That gallery left a lasting impression,” Banele recalls. “It only displayed one artwork but the intentionality behind it was unforgettable. It showed me you don’t need a grand space — you just need to be deliberate about what you do with it.”

This philosophy became the foundation of BKhz. Every exhibition is meticulously curated, from the colour of the walls to the atmosphere, ensuring each show feels distinct and deeply considered.

“For us, it’s not about volume, it’s about quality. We want every detail to reflect the care and research we pour into our work.”

BKhz first opened its doors in 2018 in Braamfontein, a hub for Johannesburg’s young and creative, before relocating to the modern and sophisticated Rosebank where it re-opened in 2021.

For Banele Khoza, establishing the gallery wasn’t just about showcasing his own work but creating opportunities for other artists.

“I knew I wasn’t the most skilled in the room,” he says, humbly, “but I wondered why others, who were so much more talented, weren’t getting the same attention.”

Driven by this awareness, Khoza used his platform to elevate artists like Tatenda Chidora and Mashudu Nevhutalu, whose talent he felt deserved greater recognition.

The gallery became a space for celebrating and nurturing the brilliance of his peers — a tangible way to give back to the art community.

Yet, Khoza is candid about the challenges of entrepreneurship.

“There’s this energy of resistance you face daily,” he says. “You think, ‘I can’t do this; I should quit.’ It’s a constant battle — impostor syndrome, self-doubt — but you have to push through.”

He stresses the importance of perseverance, sharing his struggles to demystify the entrepreneurial journey: “Quitting is part of the obstacle but overcoming it is what defines your success.”

The lack of black-owned galleries, and their under-representation at international art fairs, has long been a stark reality Khoza knows well.

While the numbers are slowly growing, it’s easy to feel excluded from the traditional art system. But he sees this shift as an opportunity.

“What you think are your limits can actually be your strengths,” he reflects, noting limitation often sparks creativity, a vital asset in a field where innovation is the driving force.

“I would also just encourage angel investors to take on entrepreneurs in the art space at an earlier stage, because if you have the right investor behind you, they could also help you with mentorship and to devise strategies that aid you to stay in business,” he adds.

Last year, Khoza says, was a turning point for him in understanding the art business.

“The art world really shifted economically in 2024,” he explains. Sales weren’t as predictable and many galleries, including in New York, closed their doors due to these changes.

This was a wake-up call to rethink what it means to run a gallery in such an environment. As both an artist and gallery owner, he has reinvested his earnings in BKhz, embracing the challenges of entrepreneurship with a sense of resilience and creativity.

BKhz has become a launchpad for some of the most exciting voices in contemporary South African art. Among its distinguished past exhibitors is Lunga Ntila, who died in 2022, a celebrated multidisciplinary artist who was known for her striking digital collages that explored identity and culture.

Notably, Ntila was the first artist at BKhz to debut with a solo show rather than starting with a group exhibition — testament to Khoza’s belief in her unique vision.

Zandile Tshabalala, whose vibrant figurative paintings celebrating black womanhood had already garnered international acclaim in Germany, also had her South African debut at BKhz.

Khoza’s gallery provided a homecoming stage for her, affirming its role in connecting global recognition with local audiences.

Wonderbuhle, a rising star known for his emotive and textured storytelling through mixed media, has exhibited at BKhz twice and has also showcased his work on world stages.

Most recently, the gallery welcomed Nelson Makamo, one of South Africa’s most respected contemporary artists, known for his dynamic portraits that centre the beauty of African youth.

Through these collaborations, BKhz continues to position itself as both a nurturing ground for emerging talent and a prominent space for established artists to experiment and connect, seven years since its establishment.

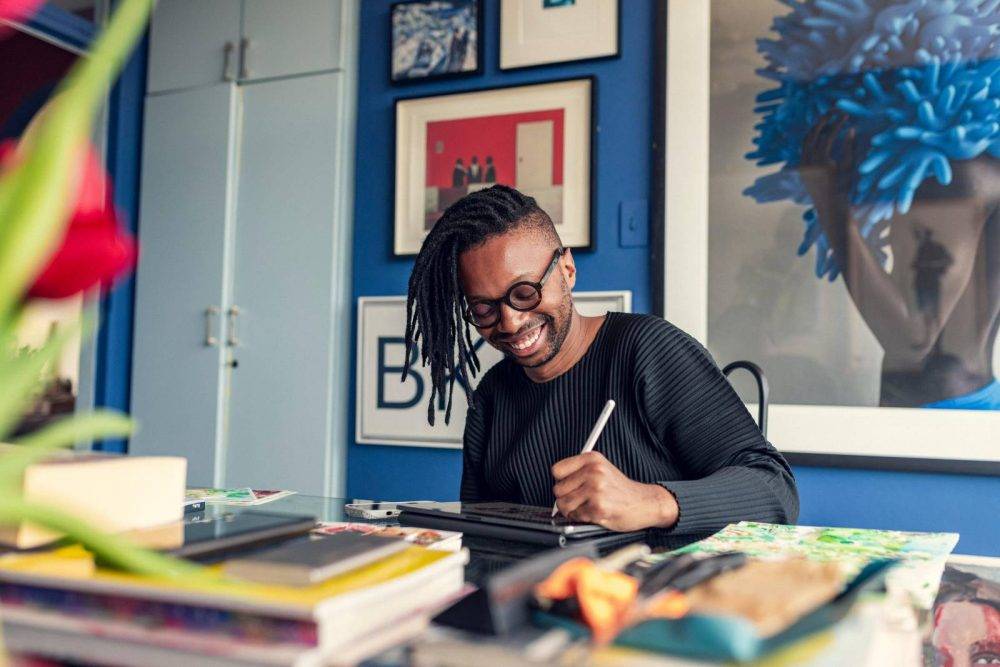

Not to be brushed aside: A trip to Paris inspired artist and curator Banele Khoza to start the BKhz gallery in Rosebank, Johannesburg.

Not to be brushed aside: A trip to Paris inspired artist and curator Banele Khoza to start the BKhz gallery in Rosebank, Johannesburg.

Art on the move

Lebo Kekana is an innovative 24-year-old who didn’t allow the prohibitive cost of paying for a physical space stop him from pursuing his gallery aspirations. Four years ago, he established what he describes as a “nomadic curatorial project” called Fede Arthouse.

His is an art gallery that exists without a permanent space and instead hosts exhibitions through collaborations with other galleries.

Growing up on Johannesburg’s East Rand, Kekana wasn’t exposed to the art world but a move to Cape Town opened his eyes.

“When I started going to galleries in Cape Town, I realised this was a thing,” he explains.

Despite lacking a formal arts background, he decided to create a space for young people like himself.

“I didn’t study the arts at all,” he says. “I was a computer science student when I felt the need to exist in the art world.”

It was during one of the Covid lockdowns that Kekana found the freedom to explore his growing interest in art.

“I started painting and realised how much I really enjoyed it,” he recalls. “I wanted to pursue it seriously.”

In 2020, he rented a house in the Woodstock neighbourhood of Cape Town and reached out to other emerging artists to create his first show. Fede Arthouse began its journey in December 2020, with a show that set the tone for what was to come.

“I didn’t call myself a curator at the time,” he says, “but that’s when it began.”

By the following year, Kekana had dropped out of university to fully focus on Fede and his mission to make art more accessible.

“I wanted to create something that felt comfortable for me and for others like me. I didn’t want the typical white-cube gallery vibe, where people who look like me aren’t sure if they belong.

“The idea of a house with a lounge and a back garden was already quite comfortable, just by virtue of it being a domestic space.

“That’s where the name Fede Arthouse came up — just from that first show happening in the house. It just felt like it made sense and it kind of stuck.

The word “fede” comes from Tsotsitaal slang, meaning “all good”, and commonly used as a response to a greeting.

“I was inspired by a gallery I saw online that’s based in Mexico that was called a nomadic gallery,” says Lebo. “I thought it was an interesting concept, especially since I didn’t have a permanent space.

“I decided to roam around, bringing the shows to different locations. If the gallery existed anywhere, calling it Fede would act as an identity marker, giving it a sense of origin.

“Just like Tsotsitaal can vary slightly across South Africa, Fede’s shows would take on different feels, depending on where they were.”

Twenty twenty-one was a year of experimentation as Kekana navigated the complexities of curating.

By 2022, the gallery had held two more shows and, in 2023, Fede occupied a building for six months, allowing Kekana to explore his curatorial language more deeply.

During that time, Fede also hosted a residency for three Cape Town artists: Zimbabwean-born photographer Micha Serraf, multidisciplinary artist Cira Bunsby and the cultural expressionist painter David Goldsmid.

“Not having a permanent space became an advantage,” Lebo reflects.

“Every exhibition would be different and I could collaborate with other galleries or cultural spaces.

“It was a new way to engage, where Fede came in as the curatorial body with artists in tow.”

Fede has ventured internationally, with shows in Ibiza and Barcelona, in Spain, and even a presentation at Decorex in South Africa.

By last year, Fede’s reach had expanded further, showcasing its versatility across disciplines from fine art to design and film.

The gallery made its mark at the RMB Latitudes Art Fair and is set to build a more consistent programme in Johannesburg.

“I live in Joburg now with the intention of doing more shows in the city,” Kekana shares, emphasising his desire to cultivate a dynamic arts community across both cities.

Despite the challenges that go with building a sustainable model, Kekana is determined.

“There are discussions that need to happen with galleries about fair curatorial fees,” he reflects, noting that his focus is on growing Fede’s impact beyond the confines of the traditional gallery space.

Through collaborations with galleries like Blank Projects, Lemkus and Under Projects, as well as Kekana’s involvement in high-profile events such as RMB Latitudes, Fede continues to push boundaries, ensuring that art in South Africa is not confined to a privileged few.

Shape shifting: Twenty-four-year-old Lebo Kekana started Fede Arthouse, a gallery which does not have a permanent space, and instead hosts artists through linking with other galleries.

Shape shifting: Twenty-four-year-old Lebo Kekana started Fede Arthouse, a gallery which does not have a permanent space, and instead hosts artists through linking with other galleries.

Transforming from within

Starting as a young curator at the Stevenson in Johannesburg in 2011, Lerato Bereng quickly made her mark, becoming a shareholder and partner at the gallery by 2014, at just 28 years old. This was a groundbreaking achievement in a space that was still largely exclusionary.

“In terms of black ownership of art galleries in South Africa, it was few and far between back then,” Bereng recalls. “Particularly as a black woman. I don’t know that there was another like me. So, yeah, it was kind of a big moment for myself.”

Her entry into the art world began with the Cape Africa Platform’s Young Curators Programme, where she was selected as one of five trainees for an 18-month programme that culminated in curating her first exhibition. “That was where everything started,” she says.

This early experience prepared her for an invitation to curate a show at Stevenson Cape Town, then called Michael Stevenson, following her work at the Cape Town Biennial.

Reflecting on her rise, Bereng emphasises the uniqueness of Stevenson’s structure, which allowed her to grow into a directorship role.

“The structure at the time didn’t really exist elsewhere. It was rare to see power-sharing in galleries.

“Usually, the name on the door is the sole owner and the directors just work there,” she explains.

At Stevenson, however, 11 partners share ownership, a model that challenges traditional hierarchies. Three of those partners are black women.

Established in 2003 in Cape Town, Stevenson now also has galleries in Johannesburg and Amsterdam.

Bereng’s story coincides with significant shifts in South Africa’s art scene. When she began her career, it lacked non-commercial spaces and the museums struggled with funding.

“Galleries played a bit of a museum role back then,” she notes. “They were the ones bringing far more ambitious programming and introducing international artists to South Africa because the museums simply didn’t have the financial ability to do it — and many still don’t.”

This dynamic gave Bereng and her peers a unique opportunity to redefine roles in the industry.

“It was exciting to be in a space where everything was in flux. I liked that it allowed me the freedom to imagine what I could contribute.

“I could have never imagined being at a commercial gallery but Stevenson became a space where I could experiment.”

However, the insular tendencies of the traditional gallery and museum models remain a challenge.

“The gathering and museum models we see today are based on Western structures. They’re still seen as very white, elitist and exclusionary,” Bereng acknowledges.

“We don’t help ourselves with the impenetrable art history language, either. Art-speak can make people feel dumb and that’s a huge barrier to engagement.”

Yet, she sees hope in the new generation’s ability to challenge these norms.

“Spaces like BKhz are brilliant. They’re breaking down those barriers. Younger artists and curators are adopting more flexible, innovative models — like pop-ups, online platforms and artist-run initiatives.

“The nomadic curatorial project concept of a Fede Arthouse is also a great example of what’s possible.”

At Stevenson, Bereng has championed initiatives such as the Stage project, designed to spotlight unrepresented young artists alongside established names.

“We wanted to create a space with no pressure or expectations. It’s about giving young artists a chance to experiment and learn, with support from the gallery,” she explains.

These efforts have also cultivated a new wave of black art collectors.

“Through Stage, we’ve seen young collectors who are excited to engage. They’re, like, ‘Oh, I can afford this — it’s maybe R5 000. Can I do a lay-by?’ It has been nice to engage with them on those terms, using new language.”

Despite the successes, Bereng acknowledges that systemic challenges persist.

“One reason we don’t see more black-owned galleries is that it’s a tough industry. Financially, it requires a lot.

“Historically, many black people in South Africa don’t come from wealth, so without strong financial backing, it’s hard to sustain a gallery.

“It took Michael Stevenson years to break even.”

But she encourages young people to dream big.

“I’m so taken by the younger generation. They just go for it! People like Banele Khoza and Lebo Kekana decided what they wanted and made it happen. That’s what it takes — just do it in a way that’s sincere and comes from your own experience.”