Experimental: A timeline of Standard Bank’s involvement in the arts over the years in the Art Lab in Sandton City in Joburg

Walk into Johannesburg’s Sandton City mall, and your senses are gently pulled into a different rhythm, one that pulses not with consumerist frenzy but with creative contemplation.

Nestled amid high-end storefronts and bustling cafés is Standard Bank’s latest gift to the arts — a concept that’s not just a space but a gesture.

The Standard Bank Art Lab speaks less like a gallery and more like an ongoing experiment in what art can mean, where it can live and who it is for.

Standard Bank has long worn its “Champion of the Arts” title like a well-earned badge. But that becomes more than corporate branding when you step inside this new cultural node.

The Art Lab isn’t just a white cube with expensive paintings, it’s an invitation to reimagine what happens when a bank becomes a cultural custodian, not from the margins, but from the front lines.

The story of the bank’s relationship with the arts begins with a humble portrait of Robert Steward, its first general manager, painted in 1983.

That acquisition, almost inconspicuous in intent, marked the beginning of a thoughtful, 40-year journey which has seen the bank build one of the most significant art collections in the country.

A timeline displayed in the Art Lab details this journey. It reads like a ledger of care, each year representing not only what was acquired but why it matters.

Through these acquisitions and partnerships, Standard Bank has consistently anchored itself in the evolving story of South African art.

But what sets this new space apart is its resistance to stasis. Rather than a static gallery where the past is preserved, the Art Lab is kinetic, alive with potential.

It’s tempting to ask, “Why not just call it a gallery?”

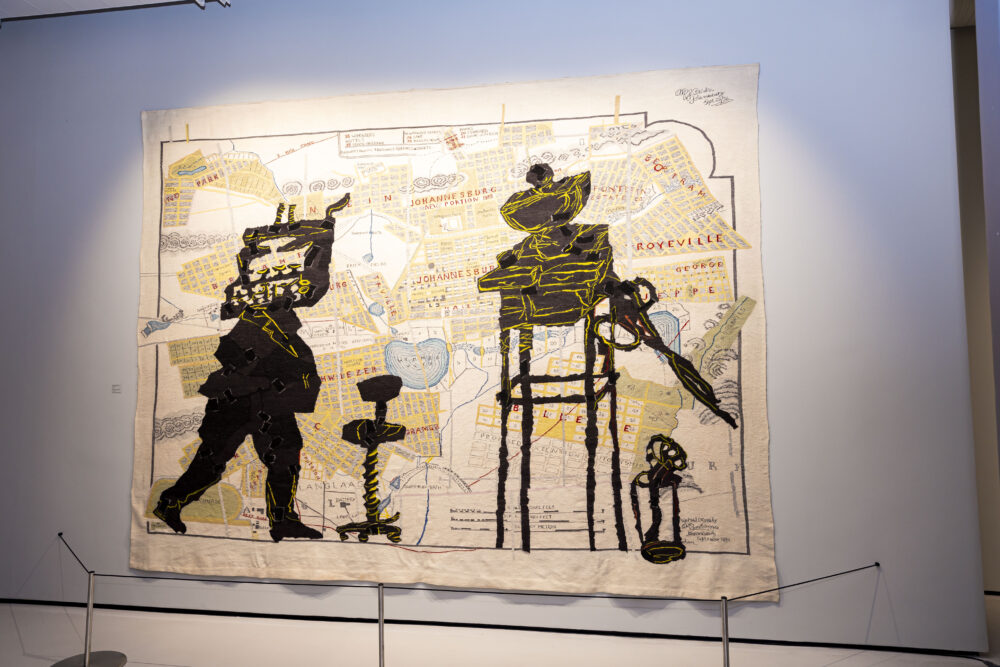

Shop around: Allina Ndebele and William Kentridge are among the prominent South African artists whose work is on display at the Standard Bank Art Lab in Sandton City shopping mall in Johannesburg.

Shop around: Allina Ndebele and William Kentridge are among the prominent South African artists whose work is on display at the Standard Bank Art Lab in Sandton City shopping mall in Johannesburg.

Dr Same Mdluli, the curator and gallery manager at Standard Bank, offers a gentle yet intentional correction to this assumption: “The space will not necessarily be strictly for fine arts or visual arts. We are also looking at exploring different expressive modes — whether it be fashion and costume as well,” she explains.

This is not semantics. It’s strategy.

By naming the space a “lab”, the curatorial team opens it up to experimentation, iteration and inclusion.

A lab suggests process over perfection, dialogue over didacticism. In the context of a mall, a place engineered for routine and consumption, the Art Lab becomes a delightful rupture, a space where art is not removed from daily life but nested in it.

It’s almost poetic, really. Just as science laboratories are spaces of discovery and disruption, the Art Lab imagines a world where art performs the same function in public life.

When you first enter, it feels disarmingly minimal. The white walls are quietly hung with works by giants like William Kentridge, Sam Nhlengethwa and Allina Ndebele. It’s not cluttered or over-curated. Instead, the display encourages a kind of breathing room, each work holding its own silence, its own provocation.

The tapestries, in particular, speak deeply. There’s something about seeing textile art — a medium historically sidelined in favour of oil on canvas, given prominence here that feels like a reclamation. The textures suggest labour, lineage and life itself.

But more exciting than what is on display is the promise of flux. The idea that what you see today may not be there next week is, paradoxically, the most consistent thing about the space. This is, after all, a lab, meant to evolve, surprise, question.

Perhaps the boldest stroke in this initiative is where the lab is situated. Not within the typical cloisters of institutional art buildings or university campuses, but inside a mall. Yes, a mall — Sandton City, no less.

This is not accidental: “We were deliberate in choosing a space such as the mall,” says Mdluli. “Not only to catch people after, or even before, a shopping spree, but to enrich people’s experience in general, especially when interacting with the space.”

This is a radical kind of accessibility. In a country where the arts are often trapped behind elite gatekeeping and geographic distance, this gesture shifts the frame.

Art is no longer something you plan a day around. It becomes something you stumble upon between errands — unexpected, unguarded and unforgettable.

Standard Bank’s gallery curator and manager Dr Same Mdluli.

Standard Bank’s gallery curator and manager Dr Same Mdluli.

“We wanted to create the sense of bringing the arts to the people,” she adds. “There’s lots of talk about bringing the arts to the people and this space is doing exactly that.”

What Standard Bank has offered here is more than a new venue, it’s a new vision. The Art Lab repositions the role of corporate support in the arts, not as a passive patronage but as a dynamic partnership with the public.

And in doing so, it asks us all to reimagine what art is for.

Is it to preserve? Yes. To provoke? Certainly. But also to participate.

To play.

To question.

And perhaps, most importantly, to belong.

In a country still healing, still negotiating the terrains of access and equity, a space like this, evolving, unpretentious — feels less like a luxury and more like a necessity.

Because art, after all, should not be a privilege. It should be part of the everyday.

And Standard Bank’s Art Lab proves that, sometimes, the most radical thing you can do for culture is simply to place it where the people are already.