Setting the scene: Dancers, choreographed by Luyanda Sidiya, in Dancing the Death Drill. Photos: Joburg Theatre

To attempt to consume such historical and artistic brilliance in an hour is, quite frankly, an injustice. Dancing the Death Drill, directed by James Ngcobo and adapted for stage by Palesa Mazamisa, is not snack theatre — it is an epic feast of thought, memory, emotion and ancestral calling.

Based on Fred Khumalo’s award-winning eponymous novel, the play is set in Paris, 1958. A double murder opens the story but soon unfolds into the haunting recollection of Pitso Motaung (played by Clint Brink), a South African soldier and survivor of the SS Mendi tragedy of 1917.

What follows is not just a tale of war and survival — but of abandonment, spiritual displacement and the impossible question of home.

The coats hanging above the stage, and the names of fallen soldiers beamed on screen, set the haunting tone as I entered the Mandela Theatre at the Joburg Theatre Complex.

The first act is certainly not for those who have read Khumalo’s novel. A few minutes in, I had to tuck my expectations aside and become a blank canvas eagerly open to indulge.

Once I found a good position for my tall stature in between seats, I settled in for an unforgettable theatrical experience.

Like Albert Khoza’s The Black Circus of the Republic of Bantu, this production is more than storytelling — it is a resurrection. A repatriation. A memorial. A calling home of spirits long scattered across oceans and continents.

The production does not simply “adapt” Khumalo’s novel — it extends it. It unearths new layers we didn’t know we needed. It voices the unheard and unseen.

Though seated for much of the performance, the 14 dancers serve as the shadows of the 823 souls of the 5th Battalion in the South African Native Labour Corps aboard the SS Mendi.

Their restrained presence is a haunting reminder of the stillness of death — and the frozen hope of those young, black men, sent to a war not their own.

Through the dancers, the audience felt what ordinary farmworkers and family men, and even the village chiefs, felt when they saw a train, boat and the ocean for the first time.

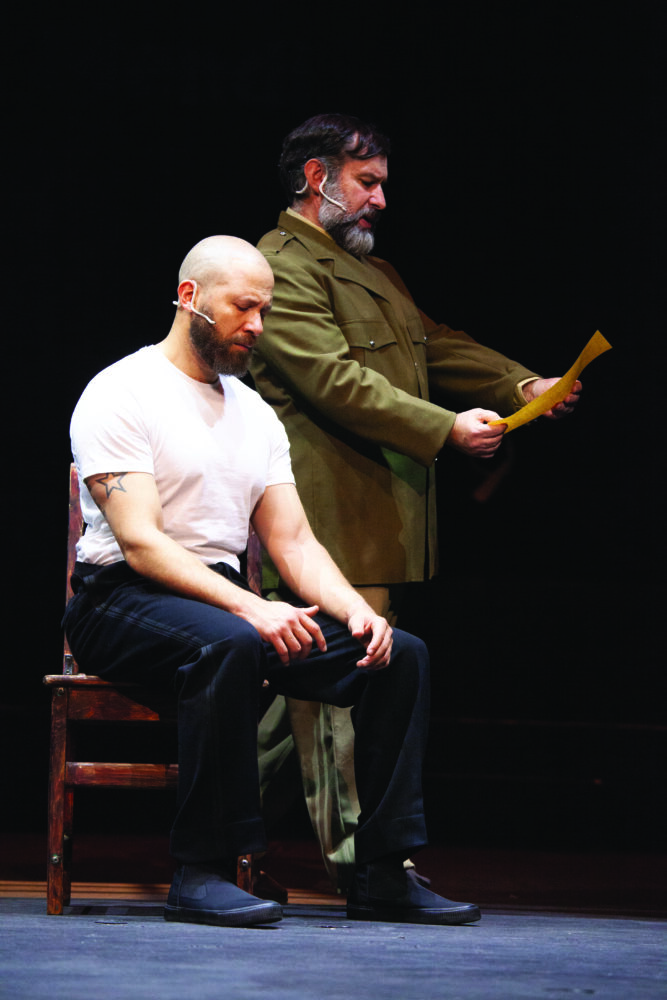

Soldier and survivor: Clint Brink as Pitso Motaung and Jose Domingos

as the investigator. Photo: Joburg Theatre

Soldier and survivor: Clint Brink as Pitso Motaung and Jose Domingos

as the investigator. Photo: Joburg Theatre

The three narrators — initially a point of concern — emerge as vital to the play’s timeline, guiding audiences between the present in France, Pitso’s past in South Africa and the harrowing events aboard the Mendi.

The eclectic mix of facts, comedy and cheer was the golden thread that stitched the overall story together.

Two of the narrators double as pivotal characters in the second act, an effective artistic choice offering emotional continuity.

While in France, Pitso, unlike Marcus Garvey’s followers who boarded the Black Star Line for Liberia in the 1900s, does not find an easy return.

“How can one go back to a place that deserted them?” he asks, echoing the silent question of many in the diaspora — discarded by their homeland, yet unwelcome abroad.

His search for identity in France is as complex as it is painful, mirroring the struggles of all those who live between.

Thokozani Nzima who plays Jerry Moloto emerges as a highlight — his voice an instrument of lamentation, praise and invocation. Whether singing in isiZulu, isiXhosa or Sesotho, his delivery evokes deep spiritual memories.. Whether singing in isiZulu, isiXhosa or Sesotho, his delivery evokes deep spiritual memories. His renditions draw immediate affirmation from the audience: a collective sigh, a nod, a release.

The play’s soul-stirring score by Msaki, and choreography by Luyanda Sidiya, elevate the narrative into a spiritual experience. What we witness is not merely 14 dancers and musicians but an invisible army of terrified, yet hopeful souls, driven by patriotism, longing and the fragile dream of something better.

The voices on stage were instruments of lamentation, praise and invocation. The delivery evoked deep spiritual memories. Hearing our indigenous languages ring out in such spaces is pleasantly profound and grounding.

This is not just a performance. It is a belly-deep release of centuries of breath held tight. It is an artistic inquest into what each man aboard the SS Mendi must have been thinking and feeling.

It gives speech to ancient, muted tongues; it gives dance to still bones. It is history, not beginning in 1648 or 1948, but rooted far deeper in the soil, the waters and the skies that have always held our stories.

As I watched, I could not help but think of the many lost and marginalised from mainstream history: The African Native Choir, Saartjie Baartman and Miriam Makeba, to mention a few. Their stories, too, are echoes of the same silencing, the same spiritual maiming.

Anchored in emotion: Thokozani Nzima plays Jerry Moloto and Charlie Bougenon as Captain Portsmouth. Photo: Joburg Theatre

Anchored in emotion: Thokozani Nzima plays Jerry Moloto and Charlie Bougenon as Captain Portsmouth. Photo: Joburg Theatre

In the book and on stage, one of the goosebumps moments is when SS Mendi is about to sink. Reverend Isaac Wauchope Dyobha cries: “Be quiet and calm, my countrymen, for what is taking place is exactly what you came to do.

“I, a Xhosa, say you are my brothers. Swazis, Pondos, Basutos, we die like brothers. We are the sons of Africa. Raise your war cries … You are going to die … but that is what you came to do … Brothers, we are drilling the death drill.”

This was not an adaptation. It was an extension. A calling back of the forgotten.

A prayer, a dance and standing ovation to the ancestors.

Unlike Fences and The Colour Purple, plays I had seen on that stage, Dancing the Death Drill affirms the need for African stories to be told — in our languages, with our rhythms and through our authentic voices.

Dancing the Death Drill runs at the Joburg Theatre until 28 September.