How close is South Africa to meeting its HIV treatment goals? We look at the numbers. (NIAID/Wikimedia)

Numbers are powerful. They can also be dangerous if not used correctly.

When the health minister said last month that 520 700 extra previously diagnosed people with HIV have been started on treatment since the end of February, the number sounded astounding.

The health department’s goal is to find 1.1-million people who know they have HIV, but either never started treatment, or fell out of treatment, before the end of the year.

In his words, the department has reached “more than 50% of the target” they set out to achieve by the end of the year.

If that gap is closed, South Africa would have met two of the three 95-95-95 goals the country signed up for as part of the United Nations plan to end Aids as a public health threat by 2030.

But knowing exactly how much the gap is closing is tricky, because people who know they have HIV may start and stop and then restart treatment again later — sometimes several times — during the course of their care. A study from the Western Cape shows that close to half of people on medication stop at least once, and that some even pause and then restart up to three times.

So, many of the 520 700 previously diagnosed people Motsoaledi says are now on medication could, at least in theory, very well be people who are counted repeatedly as they cycle in and out of treatment. But because the patient information system isn’t digitally centralised — most clinics still keep track of their clients on paper, which means different facilities can’t easily access one another’s records — someone who stops treatment at one clinic can easily be counted as a new start at another, rather than a restart.

The set of UN targets aim for 95% of people in a country with HIV to know their diagnosis, 95% of those being on treatment and 95% of those taking medication having such low levels of virus in their bodies that they can’t infect someone through sex.

“The reason that we [were] able to reach half a million within a short space of time, was because of weekly check-in meetings with provinces, where reports that come from the ground are verified in the presence of all provincial colleagues before they are regarded as final figures for reporting,” said the minister.

But simply counting better isn’t the same as doing better, and critics called the reported progress “inconceivable”.

Why?

Because for the past few years, the number of people with HIV who have gone on treatment has crept up very slowly, so much so that the gap to 95% has remained more or less the same for about five years. (At the moment just over 80% of people diagnosed with HIV are on treatment.)*

Moreover, that was while treatment programmes had funding and US-backed money for HIV projects was in place.

So now, at a time of funding shortfalls, programmes closing and the government scrambling to plug the holes, could nearly half of the number of people who need to get on treatment really have been added in just 10 weeks?

We dive into the data to get a sense of what the numbers really mean.

Mind the gap

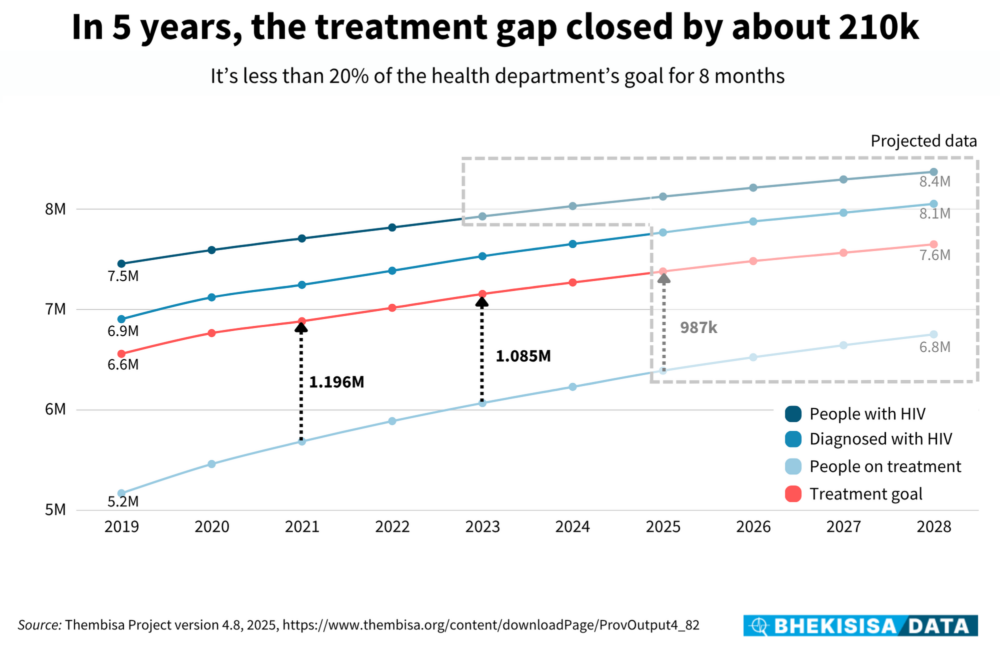

In 2021, South Africa was about 1.2-million people short of its 95%-treatment goal; by 2025 the shortfall will likely be 990 000. That means that the gap — that is, the difference between where the country actually is and where it wants to be when it comes to HIV treatment — has closed by about 210 000.

So there’s been progress, but it’s been slow: in total, only about 700 000 more people are on HIV medication today than five years ago.

“Getting that last one million or so people on treatment is not simple,” says Kate Rees, public health specialist at the Anova Health Institute. Part of the reason for this, she says, is that a large proportion of the group needed to close the gap are people who have been on ARVs before, but have since stopped.

Sometimes people miss an appointment to get a refill of their medicine because they can’t afford to take time off work to go to the clinic or they might have moved to another province or district and so they don’t go back to the facility where they first got their prescription, she explains. The longer the interruption lasts, the more hesitant people are to go back, says Rees, because they dread being treated poorly or getting “kicked to the back of the queue” for having missed an appointment, with especially people like sex workers, trans folk or men who have sex with men facing judgment.

Says Rees: “The health service expects people to be very rigid with their appointments, but life just is not like that.”

Slow progress

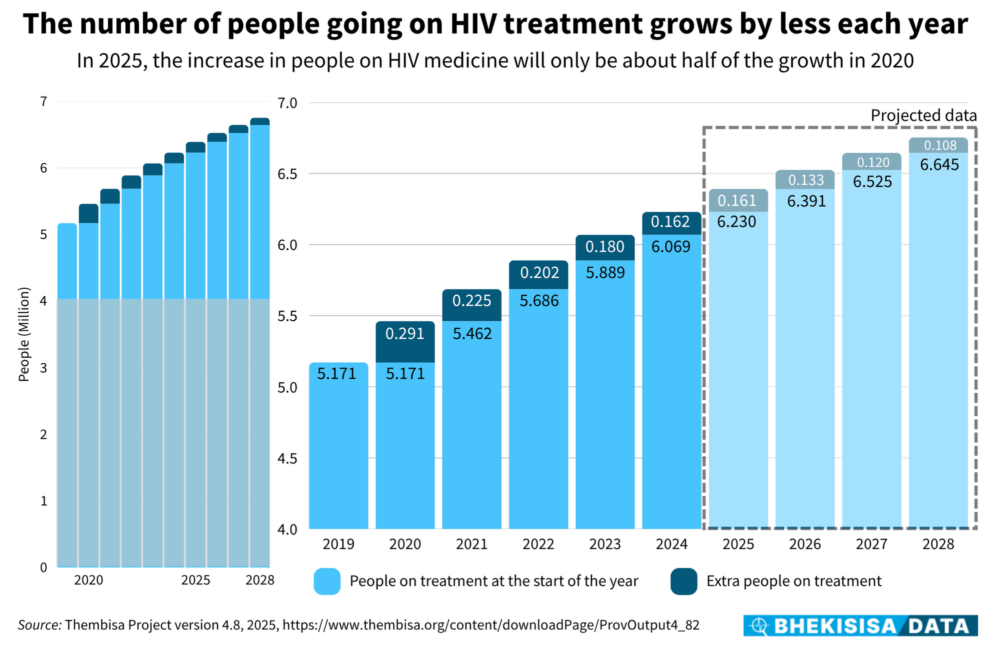

To get a sense of the progress towards meeting the UN’s second target in its 95-95-95 cascade, it’s best to look at the difference in the total number of people on HIV treatment from year to year, says Leigh Johnson, one of the lead developers of the Thembisa model, which is used to report South Africa’s official statistics to UNAids.

Although the number of people on medication is increasing, the number grows less and less each year. For example, in 2020, about 291 000 more people were on treatment than in 2019. By 2021, though, the number had grown only by about 225 000.

Current forecasts from the model are that the total number of people on treatment will grow by only about 160 000 this year. But that’s based on programmes running like they have up to now — and with recent upsets because of US funding cuts, it may be an unreasonable assumption, Johnson says.

Part of the reason for the small net gain every year, is that although many people sign up for medication in a year, many also stop coming back to get their scripts refilled. Of those who drop out of treatment, some might choose to restart within a couple of months again, while others may pause their treatment for more than a year.

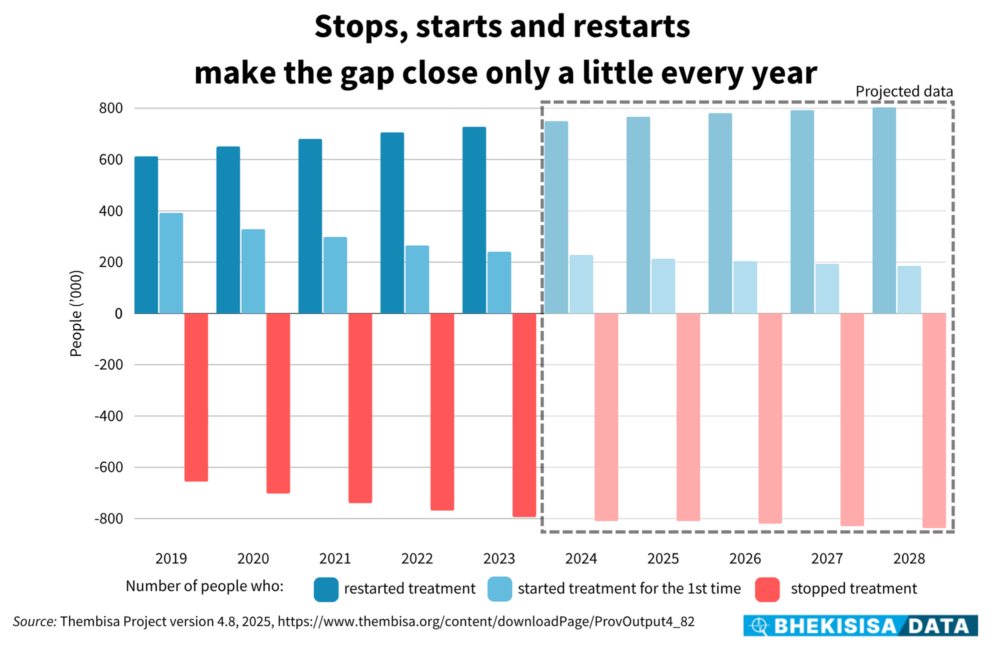

In 2023, for example, roughly 793 500 people who had been on treatment before weren’t any longer, but about 728 000 who received medication were restarters, Thembisa numbers show.

So even though some people who stop taking their medication might not restart — or restart quickly — the total number who are on treatment still grows; it’s just slow-going. This means getting a handle on how close to — or far from — the 95%-treatment mark South Africa is, is more dynamic than simple addition.

Stops, starts and restarts

“There will always be people who interrupt their treatment,” says Rees. “It’s not possible to keep everyone perfectly in the system all the time — that’s life.”

But what’s important, she says, is to make those pauses as short as possible by helping people to get back on medication quickly and easily — without judgment.

Gesine Meyer-Rath agrees. She’s a health economist at HE2RO, a health economics research group at the University of the Witwatersrand, and focuses on how the government can get the most bang for its buck in its HIV programme.

Data in the Thembisa model shows that over the years, the number of people starting medication for the first time — in other words, those who have never been on treatment before — has shrunk, but at the same time counts of restarters have grown. Her group’s analyses have shown that honing in on keeping people on HIV treatment is the best way to go — especially now that funding is shrinking — and that “we can close the 1.1-million gap through improved retention alone”.

But to plan sensibly, she explains, policymakers should know how many people are first-time starters, how many pause treatment but then restart, and how many stop and don’t come back at all.

“The more detail programme planners have in the data, the better,” she says. “The [government’s] ‘Close the Gap’ campaign has a lot of good ideas, but having the right numbers of where the gap is that we want to close is crucial, as is keeping these numbers accurate as we progress.”

This is exactly where things can become tricky in future if the holes left by the US funding cuts aren’t plugged.

Because of the US’s aid withdrawal, about 40% of South Africa’s HIV data capturers will likely have lost their jobs by September, Bhekisisa reported last month, and this means the information needed to shape where money has to be spent to make real progress in ending Aids as a public health threat over the next five years simply might not be available.

Says Meyer-Rath: “The less data we have, the more we’re flying blind, which leaves space for bickering over the data that is still there.”

This story was produced by the Bhekisisa Centre for Health Journalism. Sign up for the newsletter.