Drinking just one sugar-sweetened beverage (for example sodas or fruit juice with artificially added sugar) a day raises the chances of a child being overweight by more than half. (Towfiqu Barbhuiya/Unsplash)

Apples, oranges and grapes are healthy fruits. But when they are turned into juice they pack as much, or more, sugar than some sodas or energy drinks.

Under South Africa’s proposed food labelling regulations 100% fruit juices won’t be required to show a high sugar warning on their packaging because their sugars are “naturally occurring”. But because of their sugar content, nutritional experts say, when people consume too much of them, there isn’t really a healthier option between soda, flavoured water and energy drinks.

“Coke has too much sugar, but fruit juices also have too much natural sugar,” says Edzani Mphaphuli, executive director of Grow Great, a nonprofit which works to shape childhood nutrition policies.

Sugar is helping drive South Africa’s obesity rise. Over one in 10 children under five are already overweight and researchers have found that drinking just one sugar-sweetened beverage a day raises the chances of a child being overweight by more than half.

That’s part of what our proposed food labelling regulations are meant to combat.

Under the current draft — which the health department is still reviewing, according to spokesperson Foster Mohale — fruit juices will fall through a definition loophole. But that’s not what researchers who gave input on the rules recommended or what many public health experts advise.

“Our evaluation used the criteria of ‘free sugars’, where all 100% fruit juices would have carried a warning label,” says Tamryn Frank, a researcher at the University of the Western Cape who was part of the technical team. “That highlights the importance of reconsidering the best term to include when the final regulation is published.”

The World Health Organisation (WHO) says “free sugars” are sugars added to products like sodas and energy drinks, as well as those naturally found in fruits. But our current draft proposal says only products with “added sugar” will be required to carry a label.

The draft regulations say any drink with more than 5g of sugar (just over one teaspoon) per 100ml, or any amount of artificial sweetener (such as the calorie-free chemicals aspartame or sucralose) must show a black-and-white triangle with the word “warning” in bold capital letters.

If passed in their current form, researchers say almost six in 10 of all sodas, energy drinks and juices sold at supermarkets in the country would carry a warning label. But while 94% of soft drinks and 97% of energy drinks would need warning labels for high sugar or artificial sweeteners, just 30% of juices would be labelled.

Pure 100% fruit juices won’t carry a warning label because their sugar is natural. But not all juices are completely natural — some contain added sugar or sweeteners — so those with more than just over a teaspoon of sugar per 100ml will still need to carry a “high in sugar” warning.

We did the sums to work out which drinks have the most sugar and which will — or won’t — need a warning label, according to the current version of the regulations.

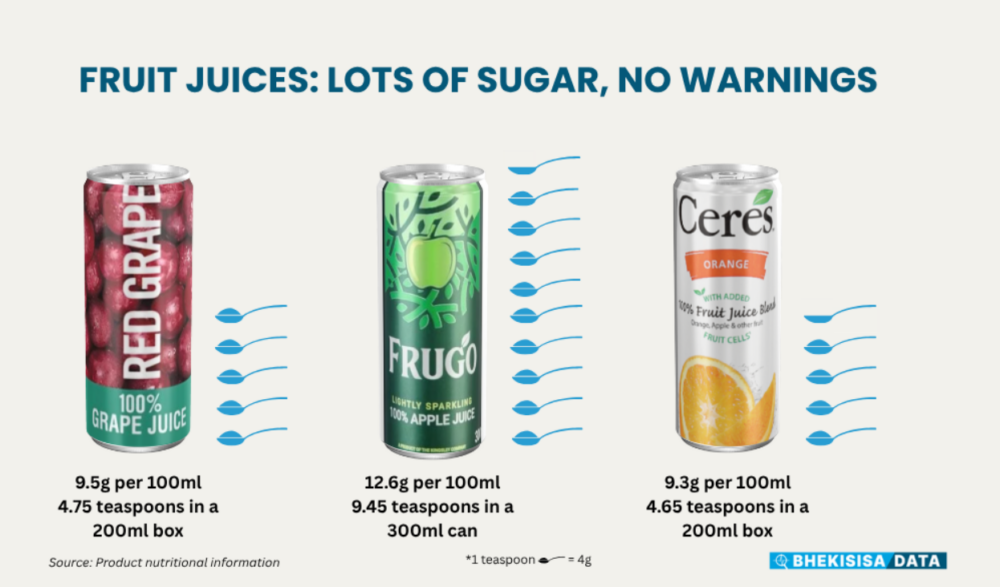

Fruit juices

While they didn’t have any artificial sweeteners, all the juices we compared — Fruugo sparkling apple juice, Ceres orange and Rhodes grape juice — had more sugar than all of the other drinks we compared, except for Coke.

“Because they come straight from nature, people think they must be healthy. But it’s not exactly the same thing as eating a single fruit,” explains Mphaphuli. “Juice is highly concentrated and you need to dilute it with water if you’re going to give it to a child [to reduce the sugar content].”

Whole fruits are filled with fibre, which slows digestion and helps control blood sugar. But that fibre is shed when fruit is turned into juice. Without it, sugar reaches the bloodstream faster, which can cause spikes and drops in energy.

Research has shown that swapping a fruit juice for some types of whole fruit three times a week can lower a person’s chances of getting type 2 diabetes — probably because juice raises blood sugar faster and has less fibre.

A study published in the South African Journal of Clinical Nutrition earlier this year found that almost three-quarters of fruit juices have more sugar than the proposed limit. But, as regulations stand now, only 17% would require a warning label because most of the sugar is natural, not added (because the regulations only look at the total amount of sugar in products with added sugar and not those with natural sugars).

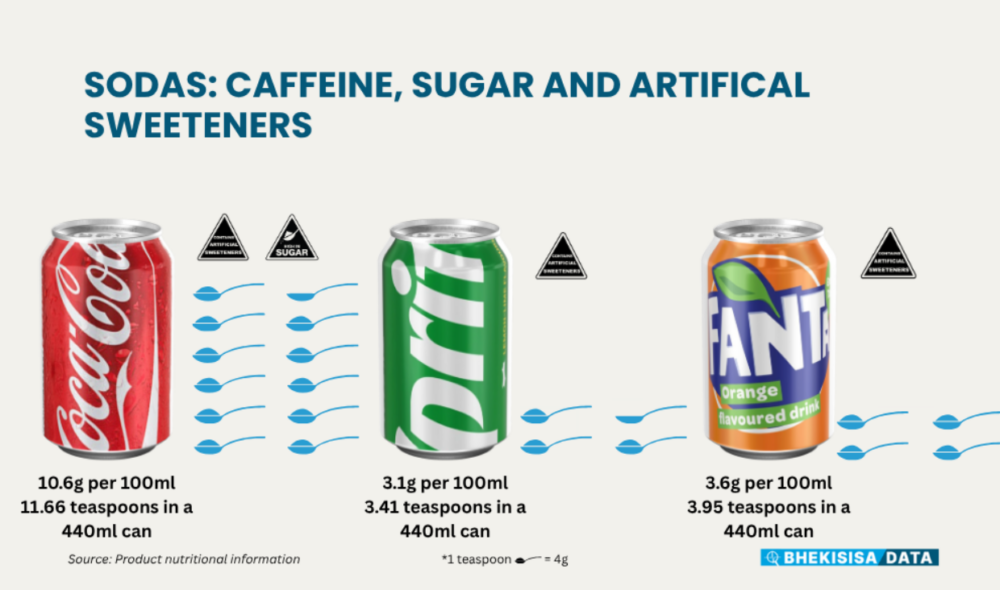

Sodas

Among the three sodas, Coke has the most sugar — and is the only one that contains caffeine, a stimulant, which means it speeds up the messages travelling between the brain and the body, and can therefore make you sleep less well. Too much caffeine can lead to anxiety, restlessness and affect the way your heart beats.

The WHO says an adult should not consume more than six to 12 teaspoons of sugar per day. A can of original taste 440ml of Coke contains 2.65 teaspoons of sugar per 100ml, which means an entire can contains about 11.5 teaspoons of sugar — more than the maximum WHO daily limit.

Sodas are some of the sweetest drinks you can buy and, research shows, South Africans love them: we drink an average of 254 Coca-Cola products per person per year, almost triple the global average of 89.

Before South Africa’s tax on sugar beverages was introduced in 2018, which requires manufacturers to pay 2.1 cents tax for every gram of sugar that exceeds 4g of sugar per 100ml, the average 330ml can of soda had about 10 teaspoons of sugar. But, to avoid the tax, some producers changed the ingredients in their drinks. For example, says Frank, Sprite and Fanta drinks lowered the sugar content but added non-nutritive sweeteners to keep the sweetness.

While chemical sweeteners, which are often used in “diet” drinks, can help people with short-term weight loss, the WHO says they should “not be used as a means of achieving weight control or reducing the risk of noncommunicable diseases” like obesity in the long run. Meanwhile, the International Agency for Research on Cancer has listed aspartame, a sweetener found in diet drinks such as Fanta Zero, as a possible cause of cancer, though more research is needed.

The new regulations will require sugary drinks containing artificial sweeteners to carry the following warning on the front of the container: “This product contains artificial sweeteners. Excessive consumption may be detrimental to your health.” Manufacturers will also not be allowed to market such products to children.

“None of these products are recommended as part of a healthy diet because they don’t contain any nutrients other than sugar and energy,” says Makoma Bopape, a nutrition researcher and lecturer at the University of Limpopo. Bopape was part of the technical group who worked on the labels. “What makes it worse is the fact that some contain sweeteners.”

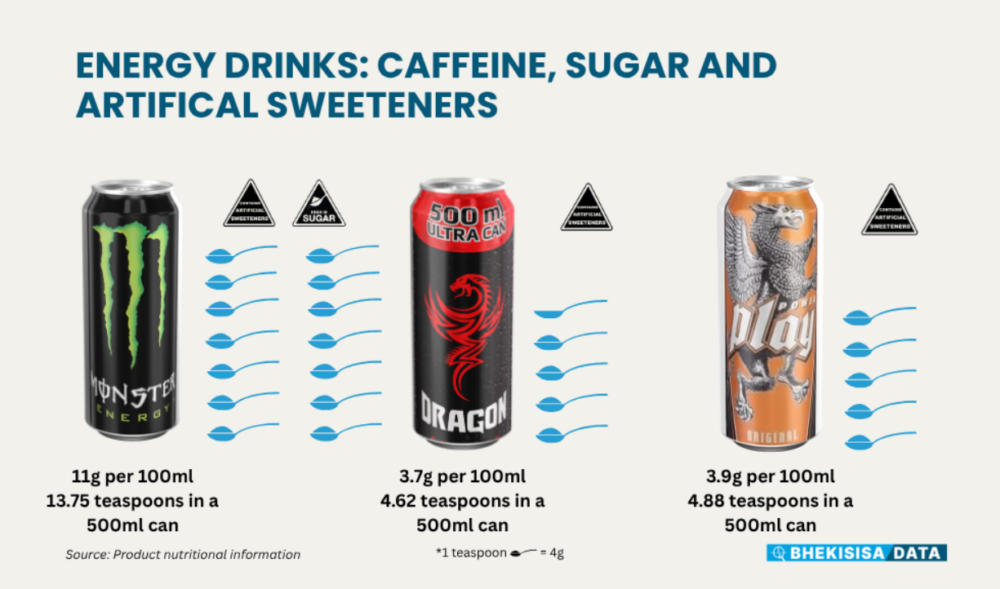

Energy drinks

Monster has nearly four times more sugar than both Dragon and Power Play and all contain artificial sweeteners.

A 500ml can of Monster has around 13 teaspoons of sugar — more than the maximum sugar intake the WHO recommends for adults per day.

Energy drinks aren’t just packed with sugar, like many sodas, they also contain caffeine. Experts say teens who weigh between 40kg and 70kg shouldn’t consume more than 100mg — 175mg of caffeine a day. At an average of about 150mg, all three energy drinks contain almost the maximum amount of caffeine per can per day that experts recommend.

Under the proposed regulations, these three drinks would all need a warning label — either for high sugar or containing artificial sweeteners.

Flavoured water

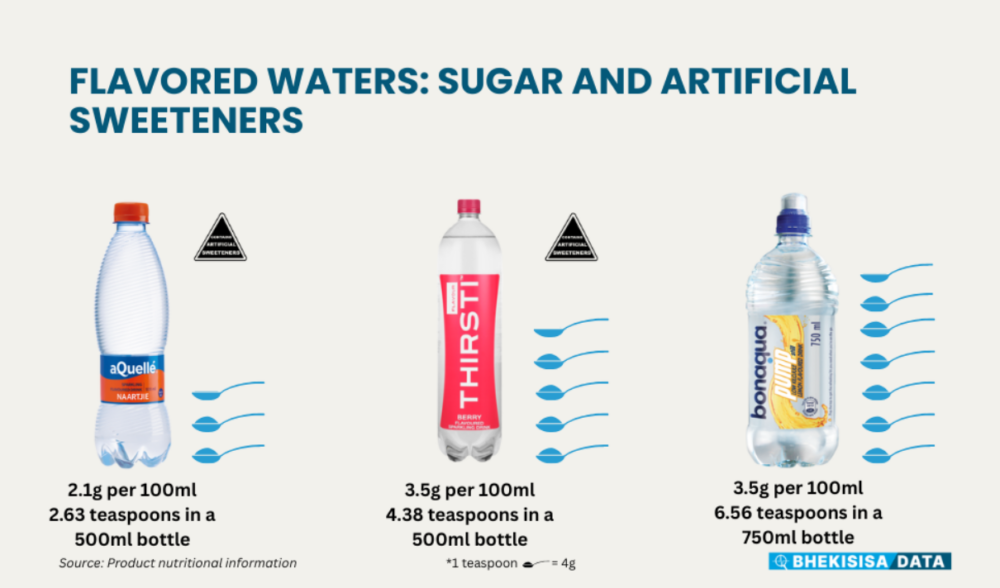

Of the three flavoured waters we looked at, Bonaqua Pump Lemon is the only one that does not contain any artificial sweeteners.

Even though they’re often marketed as “healthier” options, the flavoured waters we looked at had similar amounts of sugar and sweeteners as sodas. One option had both sugar and three sweeteners — making it more soda than water.

aQuelle naartjie and Thirsti berry use artificial sweeteners to keep the sugar low, but they respectively also contain nearly two and four full teaspoons of sugar in a 500ml bottle.

Bopape says plain water — not flavoured water — should be the preferred drink of choice.

This story was produced by the Bhekisisa Centre for Health Journalism. Sign up for the newsletter.