We talked to Lekan Ayo-Yusuf, a member of the WHO’s study group on tobacco product regulation, about the 2025 WHO Report on the Global Tobacco Epidemic, and the Tobacco Bill. (Vaping360/Flickr)

Smoking cigarettes on a plane was normal until tobacco control laws put a stop to it.

The new normal — taking a puff on any of the latest electronic devices in a shopping centre where smoking isn’t allowed.

Big Tobacco is good at adapting. With fewer people smoking cigarettes globally, the industry has pivoted the playbook towards electronic devices like vapes and heated tobacco products (HTP).

The World Health Organisation’s (WHO) Global Tobacco Epidemic report, which was released at last week’s World Conference on Tobacco Control in Dublin, shows how graphic warnings on packaging and anti-tobacco campaigns can fight against the tobacco industry influence machine, including these new product lines.

It is a timely release for South Africa. Our own Bill, meant to better regulate tobacco products, including new ones such as electronic delivery systems, is finally — nearly seven years after first being gazetted — in front of parliament’s health committee hearing oral submissions from stakeholders. The WHO report shows what we are up against.

Pages from the playbook

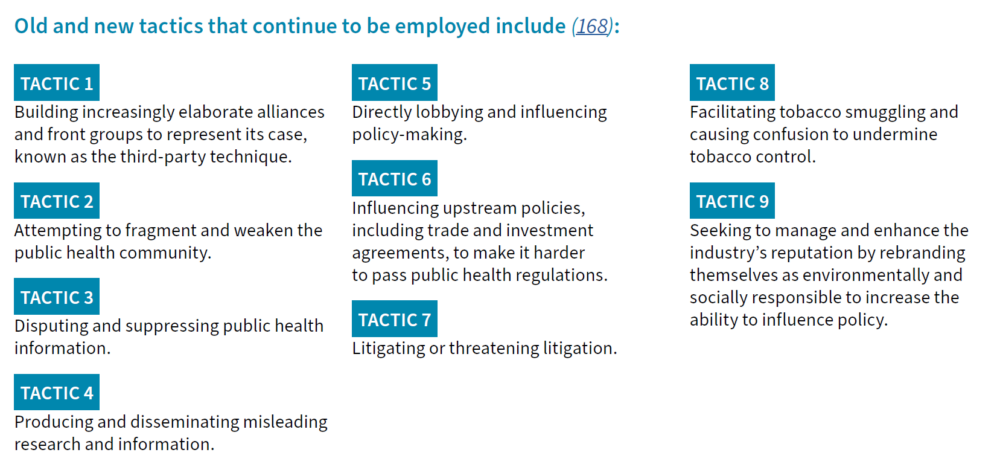

The report lays out how Big Tobacco’s well-honed tactics — and some new ones — are being used to sell new products and keep legislation to slow sales down at bay.

Among these are co-opting the term harm reduction — an evidence-based way to help lower the effects of drug use or risky behaviours on someone’s health — to push the newer products as “safer alternatives” to traditional cigarettes.

From WHO Global Tobacco Epidemic report (2025)

From WHO Global Tobacco Epidemic report (2025)

The industry has also funded their own science to discredit existing independent research on their products and pays the media to publish sponsored articles they’ve written, such as this one which appeared on TimesLIVE in November 2024, arguing there is sufficient evidence that electronic tobacco products are safe and effective harm-reduction tools, or this one published by News24 in January, boosting British American Tobacco-sponsored studies that underplay the potential harm of the chemical contained in electronic products, says Lekan Ayo-Yusuf, public health expert from the University of Pretoria and a member of the WHO’s study group on tobacco product regulation.

The industry also exaggerates the size of the illicit market in order to keep taxes low, arguing that if the government increases taxes on tobacco products, it will drive smuggling. They say plain packaging — which is what South Africa’s current draft Bill calls for — will also increase illicit trade, although the WHO says it can actually help with enforcement by making illicit products easier to detect.

In many countries, illicit trade can refer to counterfeit products or smuggled foreign cigarettes. But a 2023 study in the South African Crime Quarterly showed that in South Africa it’s more about legitimate domestic manufacturers who find ways to avoid paying proper taxes while producing branded cigarettes.

Ayo-Yusuf agrees: “It’s got nothing to do with tobacco legislation and everything to do with the criminal element in the industry.”

Where there’s smoke

E-cigarettes and vapes — electronic devices that heat a liquid containing additives and chemicals, which are often flavoured in ways that appeal to children and adolescents — and HTPs, tobacco devices that electronically heat products that contain actual tobacco instead of burning it, are defined in our draft regulation as electronic delivery systems and tobacco devices. While some of the liquids don’t contain nicotine, many do, making them no less addictive than cigarettes.

In fact, inhaling the aerosol from vapes can cause lung damage and heart problems, while HTPs still emit “tobacco smoke” with harmful chemicals — some at lower levels than cigarettes, others higher, and some not found in cigarettes.

Yet HTPs dodge tobacco rules in South Africa that bar the promotion of tobacco and public area smoking — even though they contain tobacco.

“They’re violating the current tobacco laws in broad daylight,” says Ayo-Yusuf. “You cannot market or promote tobacco products. But you see people smoking in public places and you have whole HTP stores and stands in shopping malls.”

That’s what the Bill is trying to put an end to. It will apply strict laws to newer devices: no use in public spaces; no advertising, online sales or claims that they’re less harmful than cigarettes and regulations will require graphic health warnings as well as plain packaging to deter people from using them. If it gets passed in its current form, it will also be the end of fruit-flavoured vapes — which have been heavily marketed to children — only tobacco and menthol flavours will be allowed.

We spoke to Ayo-Yusuf about the growing market for heated tobacco, harm reduction and how regulation can keep pace. This is an edited version of our conversation.

Zano Kunene (ZK): How well does SA do in tobacco control?

Lekan Ayo-Yusuf (LAY): Not well, relative to other countries in Africa and globally. The Bill is very good and will change the whole tobacco and nicotine control landscape but we have been waiting [seven years for it]. Since it was introduced in 2018, we have seen the number of smokers grow from 9.5 million to 14.9 million in 2024.

ZK: Which smoking products are tobacco companies pushing in SA?

LAY: Vapes are a big one as we had 4.1% of people between 16 and 34 years old using [them] in 2018 and now we are sitting at 7.7%. Heated-tobacco use is also increasing, which I’ve been monitoring since 2021, and using data from Nielsen to pick up on which products are being sold.

ZK: What are HTPs and how do they differ from conventional cigarettes?

LAY: Traditional cigarettes burn tobacco so you can inhale nicotine, which makes the brain release dopamine and makes you feel good, but comes with harmful chemicals from the tobacco and the paper. HTPs have a coil that is charged by a battery that heats up a stick filled with tobacco leaves. The difference is that you do not have the chemicals that come from the burning process, otherwise you have everything else.

ZK: Why does the industry call them harm reduction tools?

LAY: The industry has jumped ahead to say they reduce harm, but what we actually know is it reduces exposure to harmful chemicals. In theory, they could lower harm over time, but it is not a linear process. Whether lowering toxins from 100 to 20, for example, is enough to reduce your harm from cardiovascular disease or cancer will take you a long time to find out.

The industry says they are targeting smokers trying to quit. The easiest evidence for this would be a drop in cigarette smoking. But since e-cigarettes entered the market in 2010, there is no evidence showing that smoking has reduced.

ZK: Are people swopping cigarettes for these products?

LAY: We are not seeing an exchange. Some people are actually smoking heated tobacco or vapes plus their cigarettes. There are also about 32% of people [between 16 and 34] who have never smoked who are using e-cigarettes, an increase from around 14% in 2018.

This story was produced by the Bhekisisa Centre for Health Journalism. Sign up for the newsletter.