A throat ulcer. Bloody urine. A sick baby. That’s what smokers in other countries see. In South Africa? For now, it’s a tiny black box. Photo: Canva

In Bangladesh, cigarette packs show a photograph of an ulcer on a throat or someone on a ventilator. Mexico’s show bloody urine in a toilet or a woman with breast cancer. In South Africa, a small black box reads: “Warning: Smoking kills”.

When warning signs are big, graphic and swopped out regularly, they stop people from smoking, according to the World Health Organisation’s (WHO) latest Global Tobacco Epidemic report.

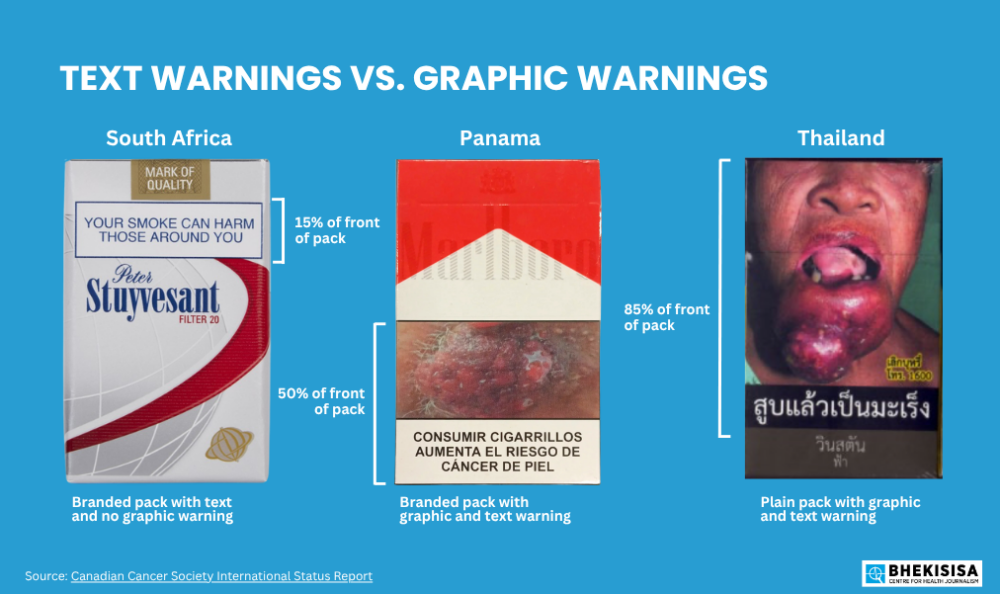

Yet, despite the WHO finding South Africa — along with Lesotho — has the highest proportion of adults who smoke daily in Africa, our warnings are outdated. The regulations, last updated in 1995, require health warnings that cover 15% of the front of a cigarette pack, far below the WHO’s recommendation of at least 50%.

Local cigarette packs have eight different warning texts such as “Danger: Smoking causes cancer” and “Warning: Don’t smoke around children”, but none show images. There are also no warning regulations for e-cigarette packaging, which often have fruity flavours wrapped in colourful pictures that targets the youth, says Lekan Ayo-Yusuf, public health expert from the University of Pretoria and a member of the WHO’s study group on tobacco product regulation.

“We don’t have graphic warnings [which is a problem because] many people can’t read the text that’s only in English, and we don’t enforce laws around advertisement, particularly for e-cigarettes.”

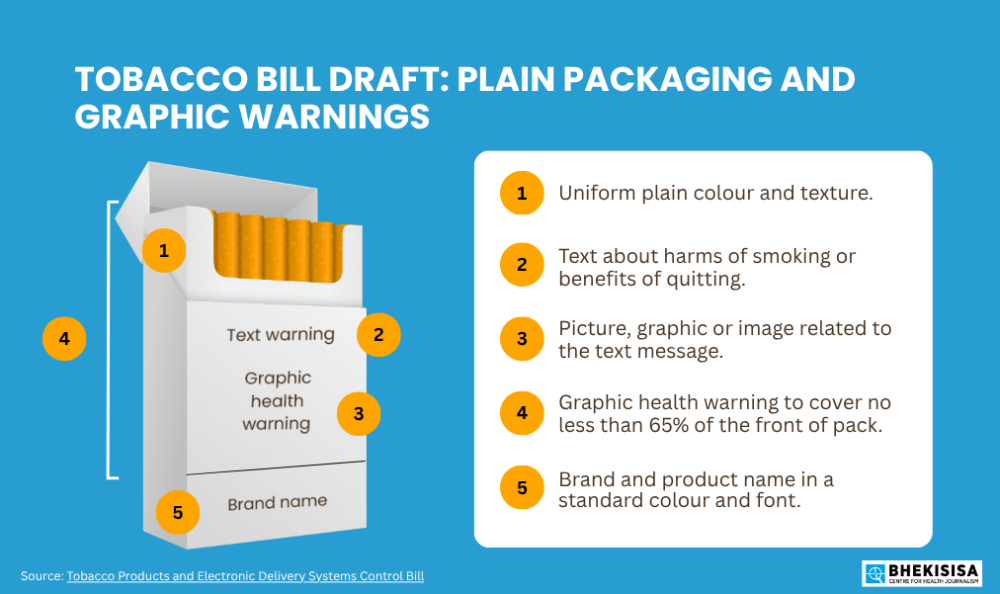

That will change if parliament passes the Tobacco Products and Electronic Delivery Systems Control Bill, which would require all tobacco products (including e-cigarettes) to have plain packaging and a graphic warning that covers at least 65% of the front of packaging.

‘Weak’ text only warnings

The WHO recommends cigarette pack warnings as one of six ways to stop people from smoking, along with tracking tobacco use and raising taxes on it. These warnings should be graphic, in colour, cover at least half of the pack, alternate often to target different groups — such as pregnant women and the youth — and be printed in a country’s main languages.

Picture warnings showing the harms of smoking, like blackened lungs or children in hospital beds, are harder to ignore than text warnings alone. That’s because they keep people’s attention, help develop negative emotions around cigarettes like fear or disgust, and lessen the desire to start smoking or encourage quitting.

According to the WHO report, about 110 countries use cigarette graphic warnings, but 40 — including South Africa — still have “weak” text-only labels or none at all.

Canada was the first to adopt graphic warnings in 2001, using images such as rotten teeth and red eyes with texts like “When you smoke it shows” to cover 50% of the front and back of cigarette packs. Nine months after their introduction, a survey of 432 smokers found that about one in five were smoking less.

Australia, which has been using graphic warnings since 2006, introduced plain packaging in 2012 to make health warnings work better and discourage smoking. Their cigarette packs also include health warnings and can’t show branding apart from the product name. Combined with bans on public smoking and higher tobacco taxes, it has helped lower adult smoking.

‘The colour of the pack makes a difference’

Under South Africa’s proposed anti-smoking legislation, all cigarette packs sold in the country will carry plain packaging and graphic warnings.

Tobacco products will be wrapped in a uniform plain colour chosen by the health minister and must have warnings that cover at least 65% of the front and back. Cigarette packs must show messages about the harms of smoking or benefits of quitting, information on what the product contains and emits, and include pictures or graphics that show the health risks.

“Our tests show that around 80% works well … but the Bill is very good and will change the whole tobacco and nicotine control landscape,” says Ayo-Yusuf.

Local research among university students showed that plain packaging with a 75% graphic warning lowered how much satisfaction smokers get from cigarettes. Non-smokers were also least likely to want to try a plain pack compared to a branded one.

“The colour of the pack makes a difference,” says Ayo-Yusuf. “South Africans look at their pack in making a brand choice, and that choice is linked to what we call the expected sensory experience [how satisfying smoking is], which leads to smoking more cigarettes a day,”

The rules on packaging and warnings won’t stop at cigarettes. They will also apply to nicotine products like e-cigarettes (or vapes) — devices that heat a liquid containing flavourings such as gummy bear or cherry peach lemon in colourful packaging that appeals to children. While they are marketed as “less harmful” than cigarettes, because they don’t burn tobacco, they are still addictive and can cause lung damage.

Plain packaging makes e-cigarettes less appealing to young people. In a 2023 survey of 2 469 adolescents (11-18 years old) in Great Britain, researchers found that among those who had never smoked before, 40% said they had no interest in trying e-cigarettes shown in plain green packaging — compared to 33% for branded packs.

Nevertheless, plain packaging has become one of the main targets of the tobacco industry’s pushback against the Bill.

Big Tobacco strikes back

The Tobacco Bill has been in the making since 2018 but only got to parliament in December 2022 after years of contention.

Because South Africa’s rules on advertising tobacco are strict, Big Tobacco relies on packaging as a marketing tool. The industry claims that if every box of cigarettes has the same plain packaging, smokers won’t be able to tell legal from counterfeit cigarettes, which will promote illicit trade.

When cigarettes are produced illegally with fake trademarks or sold to customers before taxes are paid on the goods, it is seen as illicit trade. While companies have long exaggerated how big the illicit market is, a 2023 study in South African Crime Quarterly found it mostly involves legitimate local manufacturers who dodge taxes while still producing branded cigarettes.

“Currently, they’re already producing these cigarettes and not paying taxes. Even if [all the boxes look the same] it’s not going to make it any worse or less,” says Ayo-Yusuf.

The industry also argues that the Bill is a missed opportunity to get people to stop smoking cigarettes, because it groups “less harmful new categories of nicotine products” with traditional cigarettes — even though studies show they aren’t harm-free. But Ayo-Yusuf says their protests are premature; the detailed regulations that spell out exactly which warnings will apply to which products will only come later.

For example, current rules list eight warning texts that must alternate on cigarette packs, while smokeless tobacco products only carry one about oral cancer. “They are jumping ahead by claiming you can’t regulate vapes the same way as cigarettes. The regulation could say that cigarette packs must have a graphic of a sick baby, while vapes show an image of someone chained to addiction.”

In a parliamentary hearing last month, the industry continued to double down during public comment on the Bill, saying applying the same packaging rules on all nicotine products is too strict and should instead be tested gradually.

Once the hearings end, it will be up to the National Assembly to pass, amend or reject the Bill before it finally goes to the National Council of Provinces and then the president to be signed into law.

And if it is signed, not only cigarette packs — but the tobacco industry in South Africa — could look very different.

This story was produced by the Bhekisisa Centre for Health Journalism. Sign up for the newsletter.