‘Unsupervised, unstructured, non-standardised, unsafe and altogether substandard.’ This is what was said about the care at two public hospitals in the Northern Cape last year. But is the way quality is measured a fair test? (Delwyn Verasamy)

“Unsupervised, unstructured, non-standardised, unsafe and altogether substandard.”

This is how the health ombud’s report at the end of July described the care four patients received at the Robert Mangaliso Sobukwe and Northern Cape Mental Health hospitals in Kimberley last year.

Two later died and one was left with permanent brain damage.

In the same week as the ombud’s report, politicians’ comments about the “alarming number” of patients who pick up infections in Gauteng hospitals and a news headline alleging that duct tape was used to close an Eastern Cape mom’s C-section wound raised questions — and hackles — about the standard at which health facilities in South Africa operate.

Mention the National Health Insurance scheme — the government’s plan for rolling out universal health coverage — in the same conversation and debates become explosive.

This is where the Office of Health Standards Compliance (OHSC), a statutory body tasked with ensuring safe healthcare for everyone, comes in — and whose work the government says is “essential for our national health reform”.

The basic idea is that inspectors visit clinics and hospitals, run through a long list of requirements that have to be met, award a score for each one and then write up a report to say whether quality is up to scratch. If so, a certificate of compliance — valid for four years — is issued; if not, the facility is re-inspected later and, if still not in the clear, it gets a written warning.

But, says Susan Cleary, a health economist and head of the School of Public Health at the University of Cape Town, the measures defined in these scorecards make it “almost impossible” for an establishment to pass the test. Scoring a facility’s service quality according to measures they have little control over is unfair, she says. “The last thing you want to do is give people a job that’s impossible to do.”

Yet, given the way the inspection system tests whether a facility complies with each of the 23 standards defined by the National Health Act, it’s “almost as if we set them up for failure”, says Cleary.

“Is it then really a question of what the quality of service is,” she asks, “or is it a question of what is being measured?”

In a series of analyses, we’re diving into the OHSC’s inspection reports to get a sense of what the benchmarks are — and what they say about the state of affairs at clinics, community health centres (CHCs) and hospitals.

In this first story, we’re looking only at the public health sector — not because we think things are perfect in private establishments, but because with roughly 85% of South Africans using government facilities, it seems like the best place to start.

And as with getting universal health coverage in place, we have to start somewhere. Come with us as we look at the numbers.

The lay of the land

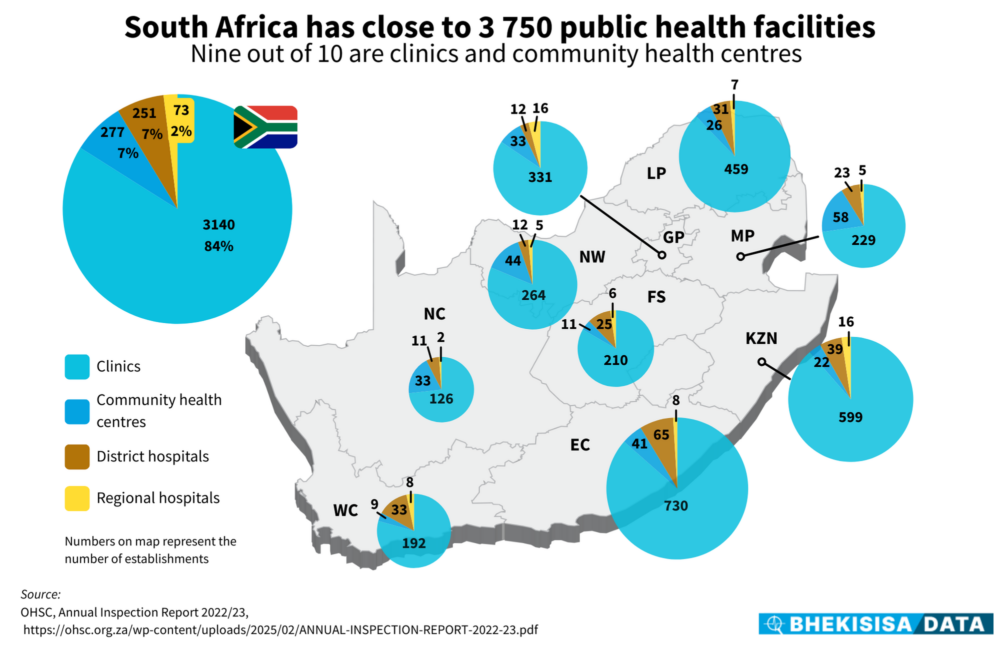

South Africa has 3 741 public health facilities, of which about 90% are clinics and CHCs. Hospitals make up the remaining 10%.

Facilities differ in their size and types of service, with clinics and CHCs being smaller and offering primary healthcare, while hospitals (including district, regional and central hospitals) can handle many patients, have them stay a day or more and deliver more specialised treatment.

Because the different facilities offer different services, the detailed list of requirements they have to meet doesn’t look the same for each place — although they all have to adhere to the same broad set of 23 standards.

For example, four inspection tools (almost like a questionnaire) have to be completed for a clinic, totalling about 90 pages of checklists. For a regional hospital, though, we counted 38 tools to be filled in across its different departments — a total of roughly 500 pages of checklists.

For this reason, one day is budgeted for doing a standards audit at a clinic, but up to five days for a hospital, depending on its size.

Counting and compliance

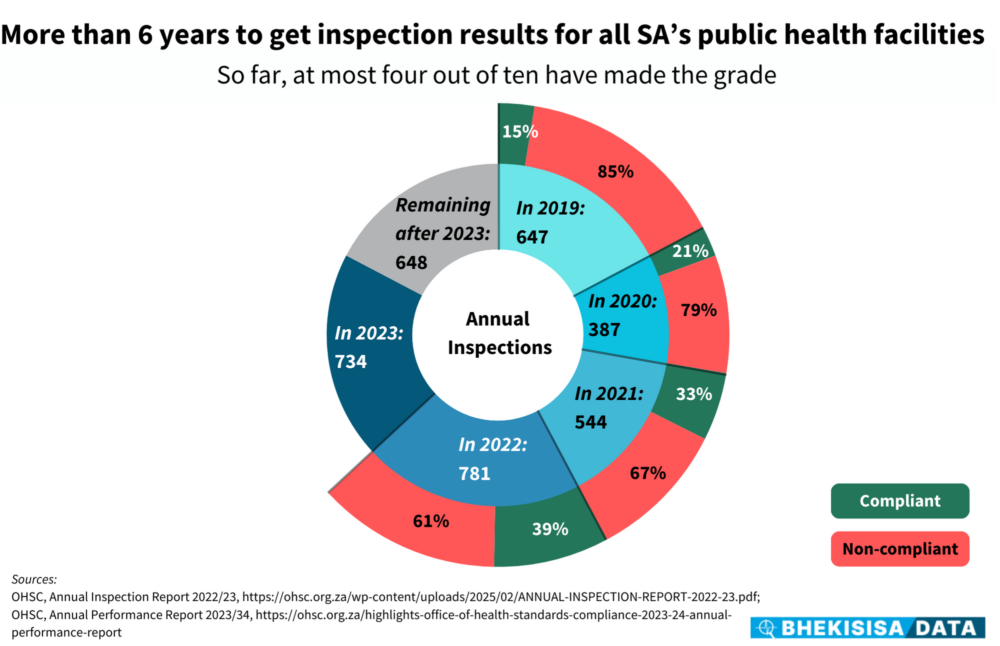

Between 2019 and 2023, the OHSC inspected 3 093 public health facilities — about 83% of the total to be assessed. Scores for the last 17% — 648 facilities — are still outstanding. (The latest inspection results available are for the 2022-23 financial year and although the OHSC has published its annual performance report for 2023-24, the inspection results for the last two years have not been released yet. The OHSC did not respond to our questions about the reason for the delay.)

Getting to every health facility in the country is a mammoth task. For example, 734 inspections in 2023 works out to two a day — and with only 53 people in the OHSC’s auditing unit at the time and the extent of the checklists, it’s not surprising that things take way longer than planned.

But the task seems even more overwhelming when the compliance rate is added into the mix. In 2022 (the latest year for which results are available), only four out of 10 public facilities passed the test and so have to be re-inspected later, meaning that the backlog builds.

To be rated as compliant, a facility has to get full marks for a set of so-called non-negotiable measures — things the standards documents say can lead to “severe harm or death” if not in place and then at least 60% for a set of vital measures — requirements that are critical to keep staff and patients safe — and 50% on essential items, “necessary for safe, decent and quality care”.

It’s an unfeasible system, Cleary says. “I think that’s a large part of what’s happened to our public sectors. [People] get given unfunded mandates all the time. But just because a standard has been set unrealistically high, it doesn’t mean that [service] quality is terrible; it may simply mean that hitting the bar is unaffordable given the money or staff available.”

Star struck or star stuck?

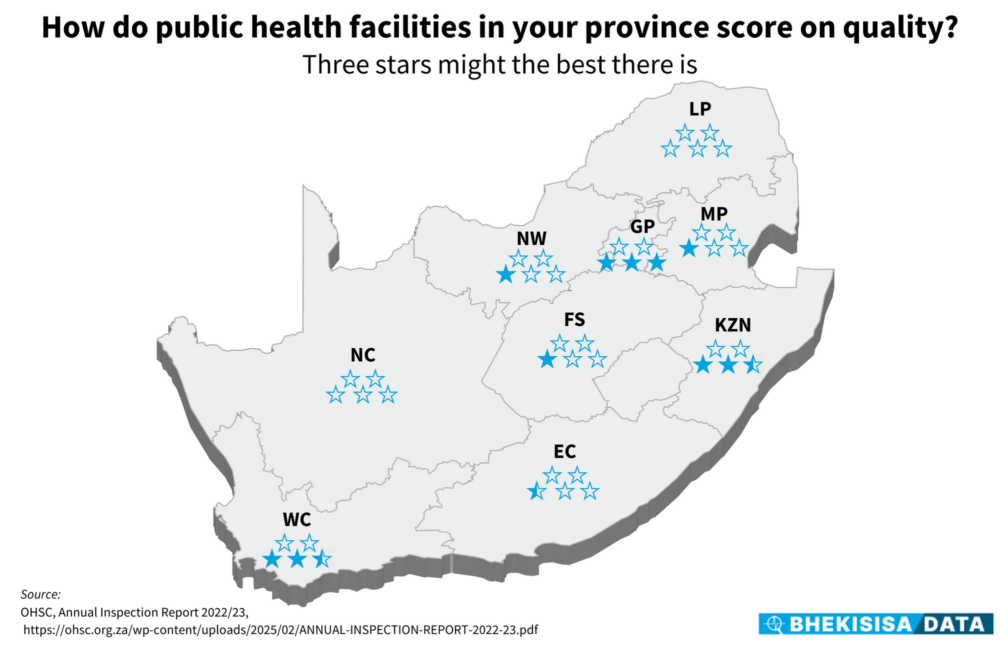

If we convert public health facilities’ compliance rates to a star rating — like you’d give a service provider on an online review — no province got more than three stars in 2022.

Looking at these results, it seems that, at best, three out of five facilities would make the cut — and it happens only in Gauteng. In KwaZulu-Natal and the Western Cape, chances are that every second facility might meet the OHSC’s list of requirements, with the other provinces struggling to get more than one out of five facilities compliant. In fact, in the Northern Cape and Limpopo, so few of the inspected facilities could pass the assessments that their scores wouldn’t even translate to a single star.

But these are the results on paper — and likely give a warped picture of what is happening in practice because of the way performance is measured.

A trimmed list of requirements — “something that 90–95% of facilities can actually meet” — could give a more realistic view, says Cleary. This doesn’t mean compromising on quality, but rather that decision-makers have to think more carefully about what the priorities really are.

“It’s partly a matter of ‘cutting your coat according to your cloth’,” she says and working from there to improve step by step — with the money to make it happen.

Says Cleary: “We have to let go of this idea that we can have everything and that it all has to be perfect otherwise it’s not good enough.”

Stats that are shocking

Something like the non-negotiable measures in the OHSC’s scorecards could give a fairer idea of what healthcare quality really looks like.

These are three things a clinic has to have in place to make the grade; the same three things in the emergency, obstetrics and clinical services units of a CHC and eight things in a hospital. They cover only statements related to handling a medical emergency, having a system in place for supplying lifesaving medical gas (like oxygen) to patients and getting patients’ consent the right way.

Viewing the quality of public healthcare from this angle really does paint a shocking picture — and could give decision-makers a concrete place to start to get to grips with claims of inadequate service.

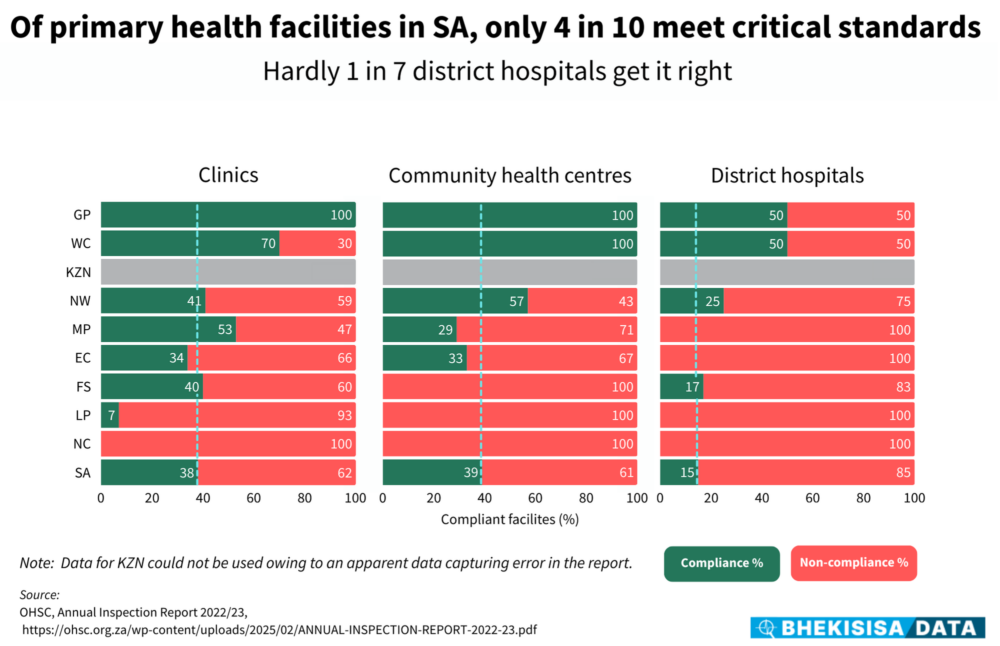

In 2022, only two provinces — Gauteng and the Western Cape — managed to have these minimum lifesaving measures in place in at least seven out of 10 clinics and CHCs and half the district hospitals inspected. (We didn’t include regional hospitals in our analysis because at most two of these were assessed in a province. A score of, say, 50% would therefore not have been a fair reflection of reality.)

In two other provinces — Mpumalanga and North West — half of either clinics or CHCs met these minimum requirements. The other provinces didn’t come close.

The health ombud’s investigation revealed that in the two Northern Cape hospitals under the spotlight, emergency power supply was non-existent and that resuscitation equipment did not work.

Looking only at these measures, the assessment that the care available to patients at these facilities was “substandard and [that] patients were not attended to in a manner consistent with the nature and severity of their health condition” would be fair — and something that leadership should be held accountable for.

This story was produced by the Bhekisisa Centre for Health Journalism. Sign up for the newsletter.