DISBANDED HOPE: Algae soup brewing in the informal settlement of Ethembeni, which means ‘hope’ in isiZulu, in Khayelitsha. (Lihle Tyala)

Sometimes what’s right in front of you is left unseen by others.

A child in pink leggings on a beach of sludge and rubbish. A schoolboy navigating a polluted stream. A minibus taxi swallowed by stagnant water. Algae soup brewing in a township swamp.

“This water, it’s all around the community,” explains Lihle Tyala, a grade 11 learner from Khayelitsha on the Cape Flats, who captured some of those scenes with his camera as part of this year’s Wellcome Photography Prize. “It’s very easy for children to play around with that water. We know that water is not healthy for them to consume. But they might even take it [in their hands] and drink it.”

ABANDONED IN ETHEMBENI: A minibus taxi swallowed by stagnant water in Ethembeni, Khayelitsha. (Lihle Tyala)

ABANDONED IN ETHEMBENI: A minibus taxi swallowed by stagnant water in Ethembeni, Khayelitsha. (Lihle Tyala)

Tyala is explaining why he and so many of the other learners who worked with the Cape Town-based nonprofit Eh!woza to show how they see climate change, mental health and infectious disease in their community, initially came back with many of the same images.

There’s something in the water. And whatever it is, it’s not good.

Still standing

The collection of photographs — “Things We Left Unseen” — is hanging in a London gallery alongside the Wellcome prize-winners, where health science meets photography from around the world, from the molecular to the meta. The idea is to get people to see some of the most urgent health problems instead of just having research papers and chilling statistics that talk over many of us.

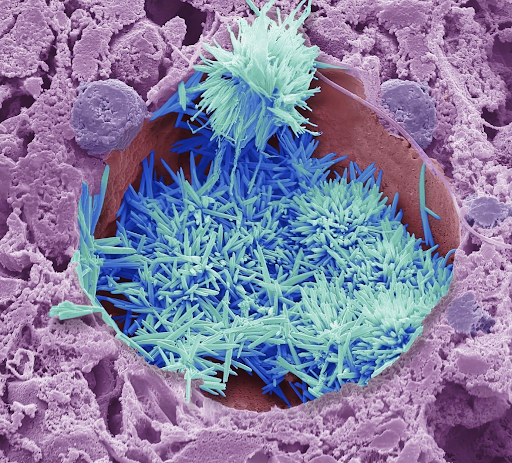

Steve Gschmeissner, a scientific photographer, created this image of cholesterol in the liver using a technique called electron microscopy, which can capture extremely small structures with very high resolution. (Steve Gschmeissner / Wellcome Photography Prize 2025)

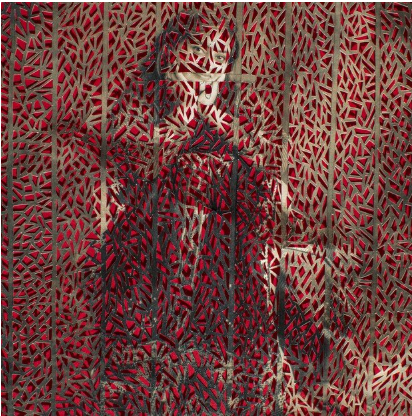

“A Thousand Cuts” by Sujata Setia studies the mental and physical trauma caused by domestic abuse in South Asian culture. (Sujata Setia/Wellcome Photography Prize 2025)

“Beautiful Disaster” was taken in the former village of Geamăna in the Lupșa area in Transylvania, Romania. In 1977 the Romanian president, Nicolae Ceaușescu, ordered the evacuation of the village’s 1 000 inhabitants to clear the way for the creation of a large lake for the storage of toxic waste from the nearby Roșia Poieni copper mines. The lake continues to grow by about 100cm a year and affects the quality of the local groundwater. (Alexandru Popescu/Wellcome Photography Prize 2025)

Mithail Afrige Chowdhury, a photographer, based in Dhaka, Bangladesh, created a scene to contrast the reality of urban expansion, asking us to consider the impacts of climate change on residents’ daily lives. (Mithail Afrige Chowdhury/Wellcome Photography Prize 2025)

“Searching for Life” captures a group of local people collecting water from a riverbed in Purulia, a district in West Bengal, India. Due to climate change, the monsoon season in the Indian subcontinent is becoming more irregular, causing rivers to dry up and many villages in this area regularly run out of drinking water. (Sandipani Chattopadhyay/Wellcome Photography Prize 2025)

Tyala had seen those pools of water before. During the Covid-19 pandemic, Eh!woza learners worked on a documentary series with Bhekisisa after a sewage pipe burst near the informal settlement of Ethembeni in Khayelitsha. It flooded the area with polluted water, the municipality leaving residents with homes seeped in it for over two months.

That pipe might have been repaired but those pools of stagnant water — a common feature across the township — were still there when Tyala came back four years later.

The water, he says, is a symbol of the infectious disease that’s endemic in the community.

“When you ask people about their health in Khayelitsha, very often their living conditions and social conditions will come up, because obviously poor living conditions are very much linked to a lot of the diseases that we have in South Africa,” says Eh!woza co-founder Anastasia Koch, who is an infectious disease researcher.

“In waterborne conditions, where there’s already poor wash systems and poor water systems, what is climate change going to do to [or already doing to] people’s health? Is it going to raise the potential for diseases like cholera and other kinds of diseases?”

Waterborne disease

It’s a rhetorical question. Reams of research say the answer to that is an unequivocal “yes”.

The connection?

An increasingly hotter Earth means climate-related rainstorms could happen twice as often as about 150 years ago, when the atmosphere’s average temperature was at least 1.2 degrees Celsius lower, scientists at the World Weather Attribution Service found.

And that means more opportunities for flooding that could result in germs that cause waterborne illnesses ending up in rivers that communities use to get drinking water, especially poorer communities, without running water or good sanitation. It also means more stagnant water pools where hosts of parasitic diseases such as malaria (caused by parasites living in mosquitos) can breed.

Cholera, a waterborne disease, spreads when someone eats food or drinks water contaminated with the germ that causes it. The bug travels through faeces and, if it spills into water, infects it. Most people won’t have any symptoms, or will have a bout of diarrhoea. But people with weak immune systems, such as those with untreated HIV, or malnourished children — both common in South Africa — often fall ill with severe watery diarrhoea, vomiting and dehydration as a result of cholera and can die from it in hours, if left untreated.

FORGOTTEN JOURNEY: Illegal dumping, poor waste management and inadequate sanitation make Khayelitsha an ideal environment for waterborne diseases to spread. (Someleze Nxenye)

FORGOTTEN JOURNEY: Illegal dumping, poor waste management and inadequate sanitation make Khayelitsha an ideal environment for waterborne diseases to spread. (Someleze Nxenye)

According to figures obtained by Medicines sans Frontières, an outbreak of cholera in Sudan has led to a suspected 100 000 cases and over 2 700 deaths over the past year. That might seem like some faraway place racked with war and poverty. But infectious diseases don’t confine themselves inside borders.

In 2023, when cholera spread in South Africa, with dozens dying from the disease, officials tracked it back to two sisters who had gone to a wedding in Malawi. South African officials are worried about cases closer to home, in Zimbabwe, Mozambique and Zambia and noted that flooding “could undermine sanitation systems and facilitate cholera transmission”.

KHAYELITSHA CHEMICAL COCKTAIL: Water, rubbish and algae. (Adaeza Okafor)

KHAYELITSHA CHEMICAL COCKTAIL: Water, rubbish and algae. (Adaeza Okafor)

After the 2023 outbreak, Tom Boyles, a senior researcher at the Clinical HIV Research Unit at Wits University, explained to Bhekisisa’s monthly TV programme, Health Beat, that contaminated water and bad sanitation also play a role in the transmission of diseases like hepatitis A and typhoid, both of which can cause fever, diarrhoea and nausea; e. Coli, some strains of which can make people sick with diarrhoea, urinary tract infections or pneumonia and organisms that can cause infections like amoebic dysentery, which causes stomach cramps and diarrhoea and can be fatal.

Bilharzia, also called schistosomiasis, common in areas in the Eastern Cape, Mpumalanga, KwaZulu-Natal and Limpopo, can be picked up by bathing or swimming in water contaminated with the tiny parasitic worm babies (cercariae) that carry it and can slip through people’s skin. It leads to stunting and learning problems in children and is also associated with anaemia, liver and kidney failure and bladder cancer. In some cases, it is fatal. The cycle of illness needs humans and freshwater snails, which host the parasitic worms, explains Boyles.

“In the Western Cape, there are none of these snails, because the climate isn’t right. So there’s no bilharzia. But as temperatures rise, the range where the snails can live will likely shift. We know that, when the climate warms, many diseases will rise. The impact of climate change on waterborne diseases is going to be large and I suspect it will mostly be through disruption from extreme weather events.”

Controlling the narrative

For the young photographers, it wasn’t all doom and gloom. It was also about art.

SUNSET OVER POLLUTED WATERS: Workshops given by Zeitz assistant curator Thato Mogotsi, photographers Musa Nxumalo and Mikhailia Petersen helped pupils learn about composition. (Lihle Tyala)

SUNSET OVER POLLUTED WATERS: Workshops given by Zeitz assistant curator Thato Mogotsi, photographers Musa Nxumalo and Mikhailia Petersen helped pupils learn about composition. (Lihle Tyala)

“I always think about the colours and how they connect with each other,” says Tyala. “There’s this one [photograph I took] where you see the sunset and you see the water there.”

The 17 young people who were selected as part of the project were taught by Zeitz assistant curator Thato Mogotsi and photographers Musa Nxumalo and Mikhailia Petersen. If you are one of those people who spend more time than you should on Google Scholar perusing infectious disease or climate change in South Africa, you’ll know the science workshop leaders: UCT’s Alice McClure, Marc Mendelson, Rudzani Muloiwa and Esmita Charani.

Combined, they helped learners tap into something deeper through their art — a worrying mix of infectious disease, mental health and climate change, something scientists are only beginning to understand.

“Think about how a person would be affected,” Tyala says. “Let’s say you were living in a certain shack and then there’s just this heavy rainfall and now your house is flooded and now you have to move out of the house. It would affect you mentally.”

Flowers blooming from tins form part of Lerato Sipezi’s collection of photographs, “Innocence Lost”. (Lerato Sipezi)

Soup kitchen soul from the KwaCaleni Soup Kitchen in Nkanini in Khayelitsha. (Thandolwethu Piyose)

Goats in Gxarha’s Kraal. (Someleze Nxenye)

The recycler’s home at dusk. (Thandolwethu Piyose)

Slide 5 of 5 caption: Gxarha’s Kraal is a make-shift zoo where everyone is welcome. (Someleze Nxenye)

Recycled riches. (Thandolwethu Piyose from her series “Small Actions Today for a Greener Tomorrow”)

But the images captured for the project are not all dire — there’s a lot of hope and beauty in the township. There’s the community recycler and the KwaCaleni Soup Kitchen, which opened during the pandemic and Gxarha’s Kraal, a makeshift zoo where anyone is welcome to stop by.

Koch says the project helps change “how stories are told about health from the Global South, giving a platform for the most affected people to start changing the narrative around health”.

And that’s what learners Hlumelo Tshingana and Anathi Vumazonke, who shot a collection of images they call “The Dirty Truth” that focused on the stagnant water, want South Africa’s leaders, and the world, to see through their eyes.

THE DIRTY TRUTH: A lake of stagnant water that some use for drinking and cooking when they don’t have other water sources. (Hlumelo Tshingana and Anathi Vumazonke)

THE DIRTY TRUTH: A lake of stagnant water that some use for drinking and cooking when they don’t have other water sources. (Hlumelo Tshingana and Anathi Vumazonke)

“Many other people just use [these pools of water] for drinking and cooking as they don’t have other water sources,” Vumazonke says. “Some people may depict us from Khayelitsha as people who do not care about ourselves or the environment … we actually do. But, sometimes, we have no control over our solutions.”

Things Left Unseen is on show at the Francis Crick Institute in London until October 18, with plans to exhibit it in South Africa later in the year.

Catch more learners’ documentaries on YouTube.

Bhekisisa receives funding from the Wellcome Trust for reporting on the impact of climate change on mental health. Bhekisisa, however, has no connection to the Wellcome Trust Photography Prize and doesn’t receive funding for any reporting on it.

This story was produced by the Bhekisisa Centre for Health Journalism. Sign up for the newsletter.