Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus (on screen), director general of the World Health Organisation, delivers a message to the multi-stakeholders hearing on the prevention and control of noncommunicable diseases and the promotion of mental health and wellbeing. Photo: UN/Loey Felipe

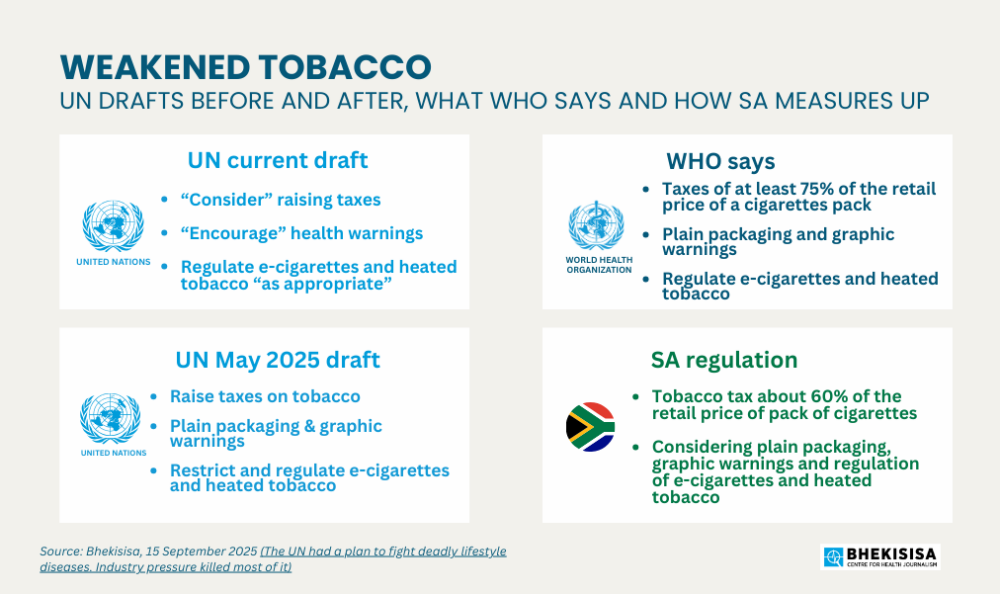

The United Nations political declaration on noncommunicable diseases (NCDs) was unequivocal. “Increase taxation on tobacco, alcohol and sugar-sweetened beverages bearing in mind the World Health Organisation (WHO) recommendations,” read the first draft of the document, which is intended as a global commitment by countries to lower deaths from NCDs.

But that draft is long gone — and public health experts say that’s bad news for our health. The draft that will be adopted at the General Assembly high-level meeting in New York on 25 September is decidedly undecided.

An NCD is an illness you can’t catch from someone else. Instead of being spread by germs as flu or TB are, NCDs usually develop over time because of the way we live (eating, drinking, smoking, exercise), our environment or our family health history.

NCDs, such as diabetes, heart disease, cancer and chronic airway ailments like asthma, caused more than half of all deaths in South Africa in 2020, up from about 100 000 in 1997 to more than 160 000 in 2018. Tobacco, alcohol and sugar (part of an unhealthy diet) are among the biggest causes of these diseases.

The latest revision of the NCD political declaration (probably the final version), which South Africa is expected to sign, went from including the words “will increase taxation” to a more palatable — at least for Big Alcohol and Big Tobacco, say public health experts — “consider introducing or increasing”. And in a big win for Big Food, the call for sugary drinks taxes is removed altogether. This was just one of many changes South African health experts are worried about.

“There is an explicit conflict of interest between the public health goals, and the goals of these corporations that generate profit from selling these unhealthy commodities,” says Tamryn Frank, an obesity and NCD prevention researcher at the University of the Western Cape. “They should not be allowed a seat at the policy-making table.”

Research backs this up. These industries employ tactics — from funding science that favours them to using front groups or courts to challenge new regulations — to delay and weaken policies on NCDs.

The eliminated and watered down wording moves away from some key recommendations from the WHO, including their proven ways to prevent NCDs, such as banning tobacco advertising and either the comprehensive regulation or banning of alcohol advertising, putting graphic health warnings on tobacco products that show the harms of these products and raising taxes. While the WHO — the UN’s health agency — gives guidance, the declaration is negotiated by member countries, which means the final wording depends on political compromise and not just the strongest health science evidence.

We break down some of the key points in the UN draft that changed, what the WHO recommends, where South Africa is on the WHO’s gold standard of compliance and how we compare with other countries.

Bad Food: Warning labels and sugar taxes

Original draft: Wanted countries to tackle unhealthy diets, excess weight and obesity by raising taxes on sugary drinks, and putting clear warning labels on the front of packs of foods with unhealthy ingredients.

Current draft: Doesn’t mention sugary drinks taxes, and merely encourages nutritional information on packaging — such as front of pack labels — rather than directly recommending it.

WHO recommendations: A minimum 20% tax — which they aim to push to 50% in 10 years — on sugary drinks so fewer people drink them, and simple front of pack food labels to help customers spot unhealthy products because nutritional information can be difficult for them to understand.

Global: Many countries already use warning labels. The United Kingdom has a traffic light system showing if a product is high, medium or low in sugar, salt and fat. Chile uses a black and white stop sign-shaped warning sign on foods high in the same unhealthy nutrients, and has taxed high sugar drinks at 18% since 2014. On the African continent, Ghana has gone further with a tax of 20%.

South Africa: The country introduced a sugar tax in 2018. It worked: many manufacturers have reduced the amount of sugar in drinks to avoid being taxed, so drinks on the market now have lower amounts of sugar and fewer people buy the drinks that still have excessive amounts of sugar, as they’re taxed and therefore more expensive. But after pressure from the sugar industry, the tax, which is based on how much sugar a drink has, works out to about 11% of retail price of popular drinks — half of what the WHO says is needed.

The health department is also deciding on new food labelling regulations that, if passed, will bring large, simple warning signs to the front of foods high in sugar, salt, saturated fat (often from animal fat or oils) and even those containing any amount of artificial sweetener.

Still, despite weaker wording in the UN declaration, Frank doesn’t expect it to slow down South Africa’s progress: “There is no reason, given our burden of obesity, for the government to delay implementing regulations, or to water them down.”

Where there’s smoke

Original draft: Strongly recommended taxes on tobacco, specifically asked countries to help lower its use with plain packaging and graphic warnings policies, and to restrict newer products like heated tobacco and e-cigarettes.

Current draft: Now raising taxes are only optional, warnings (no longer required to be graphic) are just “encouraged”, plain packaging is removed, and e-cigarettes and heated tobacco products should be “regulate[d] as appropriate”.

WHO recommendations: Taxes, plain packaging and graphic warnings are part of WHO’s six ways to stop people from smoking, which also includes offering help to smokers who want to quit, keeping track of tobacco use and protecting people from smoke. They say taxes should make up at least 75% of the retail price of a pack of cigarettes, which should also carry plain packaging and graphic warnings that cover at least 50% of the front. Newer products such as heated tobacco and e-cigarettes should also be covered under tobacco control laws.

Global: Canada uses graphic warnings, with images of rotten teeth and red eyes with texts that cover 50% of the front and back of packs. Packs in Australia carry plain packaging that make health warnings stand out better. Taxes in Mauritius and Indonesia make up more than 75% of the retail price of a pack of cigarettes.

South Africa: The same report found that South Africa’s taxes on cigarettes (based on the most popular brand) only make up about 60% of the retail price. Even though evidence shows that smoking rates drop when the tax is raised regularly, the country’s tobacco tax hasn’t increased for a long time, says Lekan Ayo-Yusuf, public health expert from the University of Pretoria and member of the WHO’s tobacco regulation study group. Taxes on e-cigarettes and heated tobacco are also far lower than cigarettes.

South Africa’s cigarettes are also branded and only have a text warning that covers 25% of the front pack. But this will change if the Tobacco Products and Electronic Delivery Systems Bill is passed. It would require all tobacco products (including e-cigarettes and heated tobacco) to carry plain packaging and graphic warnings that cover at least 65% of the front of pack.

Parliament’s portfolio committee completed hearings on the Bill last month, and have sent concerns raised by the public to the health department, before they decide on whether to proceed or halt it.

Still, Ayo-Yusuf is concerned watered down language could delay and dilute local policies: “[It] weakens political will, and risks slowing South Africa’s progress on graphic warnings, smoke-free laws and other lifesaving measures.”

Watering down alcohol

Original draft: Asked countries to lower harmful alcohol use by banning or putting stricter rules on alcohol advertising, limiting when and where it can be sold, raising taxes and enforcing drunk-driving laws.

Current draft: The revised draft recommends countries consider raising taxes. But for the other steps, it says countries should just speed up rolling out the Global Alcohol Action Plan 2022-2030, including “considering marketing and availability measures”. Experts say this is another way of weakening the language, making it difficult for countries to implement.

WHO recommendations: The WHO recommends stricter rules on advertising, restrictions on when and where people can get alcohol and taxes to get people to drink less, along with offering treatment for harmful alcohol use, lowering blood alcohol limits for driving and introducing a policy that sets a legal minimum price for alcohol products.

Global: After Russia banned alcohol advertising, introduced a zero blood alcohol driving limit, reduced the times when alcohol can be sold, and other measures, they saw a drop in alcohol use over a 13-year period. Scotland passed laws for a minimum price on alcohol units in a product in 2018, helping lower deaths caused by drinking alcohol over two years.

South Africa: South Africa taxes alcohol products by litre of pure alcohol (ethanol), which is a good structure because it encourages producers to reformulate their products with less alcohol content, says Estelle Dauchy, principal research officer at the Research Unit on the Economics of Excisable Products. Still, beer, the country’s most popular drink, is sold at some of the lowest prices in Africa, according to a July report by public health organisation Vital Strategies.

Late last year, the treasury said it is considering a minimum unit price on alcohol. The Liquor Amendment Bill, drafted in 2016, also proposed changes such as raising the legal drinking age to 21, and banning the sale of alcohol at least 500m away from schools and public institutions. Although a minimum unit price on alcohol doesn’t relate to taxation, it prevents alcohol beverage producers and sellers from “trading down” the prices of products by absorbing some of the tax increases by offering customers huge discounts.

But the process to introduce the Liquor Amendment Bill has stalled since public comments were completed in 2016. The reason? A 2025 case study that looked at meeting reports and minutes on the Bill from 2016-2022 shows that the alcohol industry has put pressure on the government, slowing the process.

Nearly 10 years later, and the Bill is still sitting with parliament, says Aadielah Maker Diedericks, secretary general of the alcohol network Southern African Alcohol Policy Alliance.

She says that the weakening of commitments at the global level has an impact for South African alcohol policy too.

Maker Diedericks concludes: “Yes, we are concerned about the watered down language in the UN and the limited inclusion of alcohol as a whole.”

This story was produced by the Bhekisisa Centre for Health Journalism. Sign up for the newsletter.