Dozens of rightful homeowners in Freedom Park, in Johannesburg South, have been left homeless — despite holding legal title deeds.

Their houses, part of a government-subsidised project, have allegedly been hijacked and illegally reallocated, often with the complicity of officials from the City of Johannesburg.

The Mail & Guardian has independently verified that the beneficiaries have valid title deeds and were allocated houses but are not occupying them. Many have been forced to live in shacks, rented rooms or even outside Freedom Park for their safety.

Simphiwe Ndlovu* applied for a house in 2004 and finally became a registered owner in 2022, but is still living in a shack with his wife and two children, in a friend’s backyard and across from one of the standout mansions in Freedom Park.

They have one bed, a TV unit, a mini fridge, a single couch and a sink. The corrugated iron sheets trap the heat in the stuffy shack, and Ndlovu dripped sweat while his wife was teary-eyed during an interview earlier this year.

“I went to the Eastern Cape and when I came back in 2022, I saw that my house was being occupied by other people,” he said.

“When I complained to the housing department, the occupants — a man in his 20s, his girlfriend and their two children — said they would leave the house. I gave them three months. When I went back, they were still staying there, and the community supported them. They told me he is not going anywhere.”

The occupants of his house received backing because other residents had procured their houses in a similarly fraudulent manner, Ndlovu alleged.

“They said the house belonged to their late uncle. But they didn’t have the papers. Someone from the housing department came with me to verify the uncle’s ID number, but couldn’t find anything, and [confirmed] that the house belongs to me.”

Ndlovu said he gets the water and electricity bill for the house from the city, totalling about R4 000 a year, and is forced to pay it for fear of being attacked by the illegal occupants, who refuse to vacate even though he has sought help from the South African National Civic Organisation (Sanco), a legal aid provider. The court gave him a protection order; but did not help him get his house back.

Forced removal: Simphiwe Ndlovu’s* home was hijacked and given to other people, allegedly by housing department officials. His family has to live in a corrugated iron shack.. Photo: Aarti Bhana

Forced removal: Simphiwe Ndlovu’s* home was hijacked and given to other people, allegedly by housing department officials. His family has to live in a corrugated iron shack.. Photo: Aarti Bhana

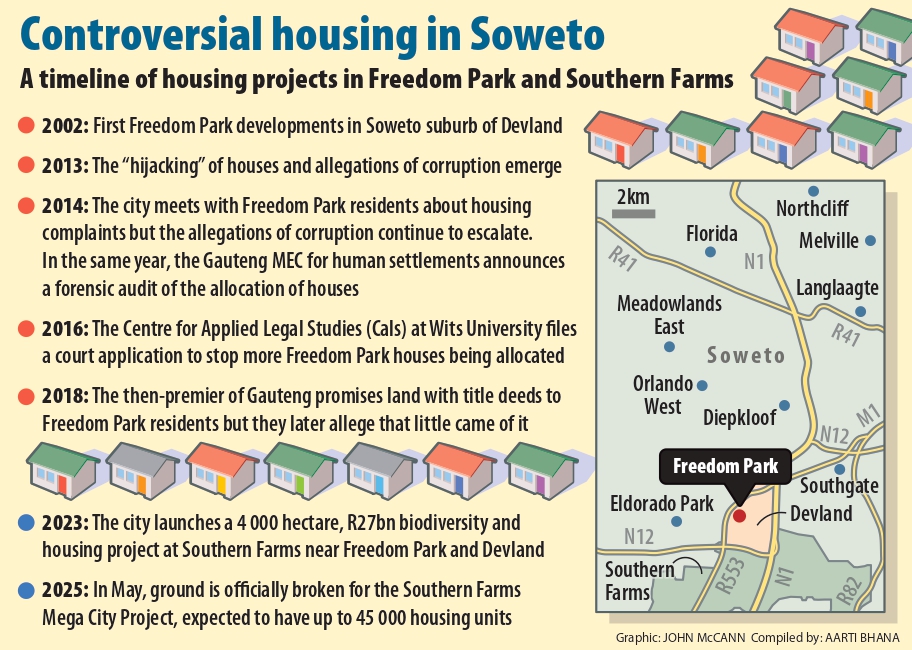

Social housing in Freedom Park has been developed sporadically since 2002. The informal settlement is located in Devland, a suburb in Soweto that runs along the Golden Highway in Johannesburg South.

It has become a mixed development, with shacks mushrooming up a hill at the entrance, two-bedroomed Reconstruction and Development Programme (RDP) houses in pastel colours deeper inside and the odd mansion or two. They stand in stark contrast to the rusted shacks, broken fences and crumbling walls that dominate the area.

A new development in Extension 35 was apparently completed in 2013. A member of Abahlali base Freedom Park, a civic organisation that lobbies for social housing, said the problem of hijacked houses started around that year.

The member, who asked not to be named because of safety concerns, alleged that ANC officials were overseeing the development, including the administration, allocation and labour, and began selling the houses to other party members and foreign nationals.

Freedom Park councillor Thobile Zondi, a member of the ANC, confirmed that this is an ongoing issue, and that more than 40 people have complained to him about not having a house despite possessing a title deed, especially in the Siyaya and St Martin wards.

Zondi said some houses were occupied by foreign nationals and that he attended to eight cases last year. The process has been arduous and he suspected that officials in the Johannesburg housing department were involved in the wrongful allocation of houses.

“There are people, I think, in the department of housing, especially when it comes to allocation, especially in that particular area, that have done a lot of wrong things. Sometimes when you engage with these residents, they normally drop names of certain officials that have allocated them or who are supposed to allocate them in their houses,” Zondi said.

The city held meetings with the people in Freedom Park on 1 November 2014 to address the housing issues. It also met with leaders in Thembelihle (Lenasia), Boiketlong Informal Settlement (Sebokeng), Thokoza/Eden Park and Slovo Park Extension 2 (Johannesburg), the 2014-15 annual report shows.

On 5 November 2014, then Gauteng MEC for human settlements, co-operative governance and traditional affairs Jacob Mamabolo announced that an audit firm would undertake a forensic investigation into allegations of corruption in the allocation of houses in Lehae, another housing development in Johannesburg South.

But the Abahlali member said the 2014 investigation was intercepted, allegedly by officials, who got the backing of local residents. The corruption continued.

In 2016, the Centre for Applied Legal Studies (Cals) at the University of the Witwatersrand filed an application at the Johannesburg high court to prevent more houses from being allocated in Freedom Park “until such time as the MEC’s office provides the forensic audit and housing allocation policies”.

This was made an order of court on 15 March 2016, but it’s not clear whether it was complied with. The M&G tried to verify this with Cals, but the centre could not provide the relevant information.

Simphiwe Ndlovu’s* home was hijacked and given to other people. Photo: Aarti Bhana

Simphiwe Ndlovu’s* home was hijacked and given to other people. Photo: Aarti Bhana

In 2018, then Gauteng premier David Makhura announced that residents in Eldorado Park, Freedom Park and surrounding areas would receive land with title deeds through a “rapid land release” programme. This was after people raised grievances about not having houses since 2017. Makhura promised more than 60 000 housing units in these areas.

Nothing substantial came out of this promise, while corruption continued in the areas where houses were being developed, the Abahlali member said.

This included Extension 35 and Siyaya. Asked earlier this year how many houses had been delivered, the City of Johannesburg said it could not find the information.

In 2023, the city launched the R27 billion Southern Farms Biodiversity Development Project, which covers 4 000 hectares, and has a mandate to deliver 16 032 fully government-subsidised units. The Southern Farms initiative covers the Freedom Park, Eldorado Park and surrounding areas, the city said.

But, said Zondi, regardless of these plans, the city still needs to investigate the cause of the corruption and hold those culpable accountable.

“They need to zoom into it, because there’s quite a number of things that went through in that area of Freedom Park in terms of allocation, because there was movement of people when they were developing Freedom Park, St Martins and in Siyaya,” he said.

“Maybe they must do an audit, or just have a hearing with those who are raising these particular cases … because some of them cannot even afford lawyers. That’s why I normally say, ‘Let us use a court of public opinion.’”

Asked about the allegations of corruption, Johannesburg spokesperson Nthatisi Modingoane said: “The city views these allegations with the utmost seriousness and reiterates its zero-tolerance stance on corruption and maladministration within its departments.”

He said the city would take a multi-pronged approach to ensure rightful homeowners can reclaim their properties, including the facilitation of mediation to explore voluntary vacation of properties or explore legal action.

“The city is actively addressing cases where rightful owners are receiving utility bills despite not occupying their properties due to incorrect title deed issuing or numbering,” Modingoane said.

“A rectification process commenced last year [2024] and is ongoing in Extension 30. Affected occupants have been issued with call notes to visit the department of human settlement’s offices in Region D, Second Street, Diepkloof, Zone 6 [which is opposite Baragwanath Mall] for assistance with these discrepancies.”

Meanwhile, residents who lodged complaints with the councillor, Sanco and the police, said they have had no success.

Vuyane Tom applied for a house in Freedom Park in 2017. He was issued with a stand number and received his papers in 2023, but discovered that the house had been occupied by people who claimed it belonged to their late father. They said Tom “bought” the house, and when he went to confront them there was a fight in the community.

(Graphic: John McCann/M&G)

(Graphic: John McCann/M&G)

“They arranged together and then came to tell me if I bought the place, I won’t get it, and I should go to the people I bought it from. I told them, I got it from the department of human settlements and I’ve got a title deed. They said I won’t get this place, and if I don’t want to die, I must just leave,” he said.

He added that some of the houses in the Extension 35 area were occupied by young people, who could not have qualified for a title deed.

He also alleged that some ANC councillors were helping people get houses.

“I think the people who are working in the ANC are the ones that know what is happening in Extension 35 and why we don’t get the houses … I’m not a member of any political organisation, so I think that’s why I am struggling to know what is happening in my house.”

Tom said he had approached Sanco and the department of human settlements in Baragwanath, where he applied for a house, but because records showed he had already been allocated a house, he was told there was nothing they could do to help him. He asked to be deregistered so he could re-apply, but was told that was not possible.

Like Ndlovu, Tom receives bills from the municipality to pay for services at the house — even though he is not living there.

“I told them I can’t pay because I don’t stay there, but they say, ‘No, it’s your place. You have to pay the services.’

“Now I’m angry. How can I pay for the services when I don’t use those services? But I don’t pay for it,” he said.

Tom lived in a shack in Freedom Park with his six children before renting a small room for R2 500 a month.

He was sitting on an old car seat, teary-eyed, while narrating his story. He said he is alone in his fight to reclaim his house and has lost hope of ever getting it back.

“Sometimes I don’t have money to pay rent. I have to make plans so that I can pay rent because we have to eat, we have to pay school fees,” he said.

“I don’t have enough money to maintain all those things, and now I’m not going to lie. I’m doing nothing. I’m staying here. At the end of the month, I will make a plan to get money, to pay rent, because no one is helping me in the community.

“I tell my kids one day we’ll get a house, but I don’t know how. But inside of me, I don’t know how, because I don’t have hope,” Tom said. I don’t want to lie. I’m staying here. I don’t have hope. I don’t know what is going to happen when. So it’s like that.”

Modingoane said the City of Johannesburg was committed to assisting residents get their houses back and would help those who sought it. He urged those with knowledge about corrupt people in the department of human settlements and housing to come forward.

“While the scale and specific nature of the Freedom Park issue are significant, the city has previously encountered and successfully resolved various housing-related challenges,” he said.

“This includes inter-governmental cooperation where the city collaborated with provincial and national departments on complex housing matters requiring coordinated efforts. Furthermore, the city has engaged in legal processes to remove illegal occupants from municipal owned land, adhering to legal protocols.”

Sanco did not respond to questions from the M&G.

*Not his real name.

This investigation was supported by the Sylvester Stein Fellowship Fund, awarded to the journalist by the Canon Collins Trust.

Stolen: Title deed holders’ homes in Freedom Park have been taken by illegal occupants, and they now live in shacks. Photo: Aarti Bhana