The Global Sumud Flotilla, a civilian fleet carrying activists from 44 countries, began its journey to challenge Israel’s blockade.

In two historic developments on Gaza this week, the United Nations Independent International Commission of Inquiry in Geneva concluded that Israel is committing genocide in Gaza, while in the Mediterranean, the Global Sumud Flotilla, a civilian fleet carrying activists from 44 countries, began its journey to challenge Israel’s blockade.

Both insist that Gaza’s devastation cannot be normalised and that international law must apply even when it unsettles the powerful. Each carries a distinctly South African imprint: compatriots at sea risk confrontation in defence of justice and a Durban-born jurist delivering the UN’s finding.

The commission, chaired by Navi Pillay, a former UN High Commissioner for Human Rights, issued its verdict after months of investigation. It concluded that “genocidal acts are being committed against the Palestinian people”, citing mass killings, starvation as a weapon of war, forced displacement, denial of medical care and systematic destruction of civilian infrastructure.

Pillay described Israel’s assault as “the most ruthless, prolonged, widespread attack against the Palestinian people since 1948”.

Earlier this year, the International Court of Justice (ICJ) found South Africa had presented a plausible case of genocide, ordering Israel to prevent further acts and allow aid. Pillay’s findings go further: hardening plausibility into legal conclusion, strengthening Pretoria’s case and raising the stakes for the international community.

Her authority is rooted in a lifetime at the front lines of justice. Raised in Durban’s Clairwood township, she became the first woman of colour to open a law practice in the city, defending detainees under apartheid. In 1995 she was appointed to South Africa’s new high court, and soon after to the International Criminal Tribunal for Rwanda, where her rulings established rape as a constitutive act of genocide.

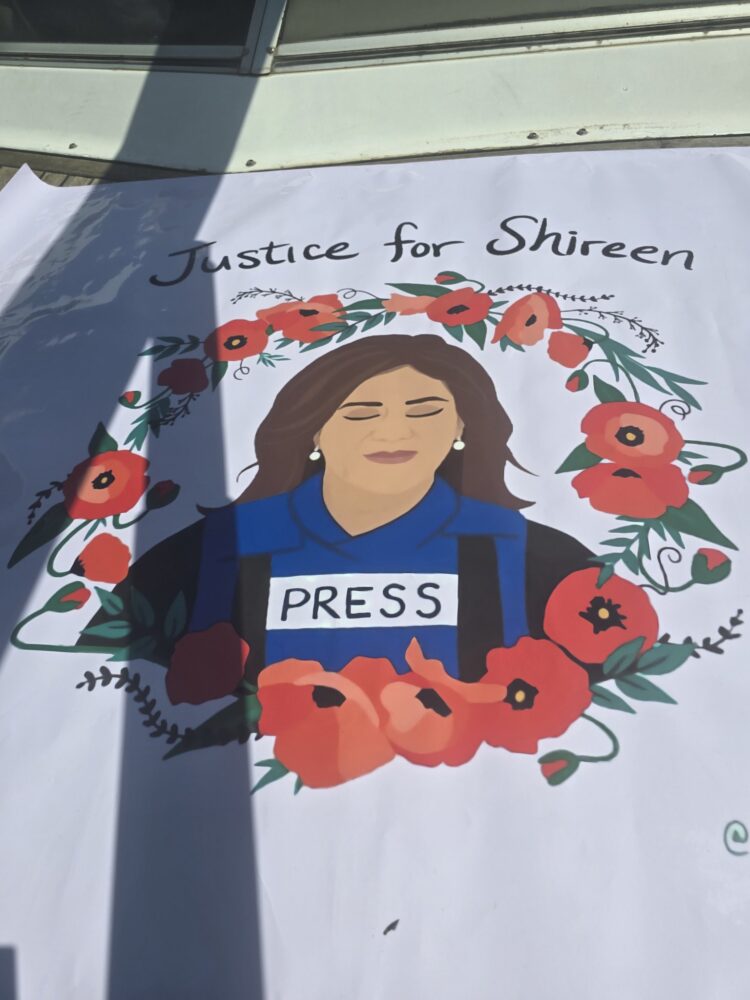

A dedicated observer vessel, the Shireen Abu Akleh, named for the Palestinian journalist killed in Jenin in 2022, carries lawyers and peace activists tasked with documenting violations and guarding against distortion

A dedicated observer vessel, the Shireen Abu Akleh, named for the Palestinian journalist killed in Jenin in 2022, carries lawyers and peace activists tasked with documenting violations and guarding against distortion

As UN High Commissioner for Human Rights, she became known for confronting power where law was at risk. Today, her insistence that “never again” must apply universally frames her work on Gaza.

While Geneva issued legal judgment, the Mediterranean saw a different reckoning. The Global Sumud Flotilla, named for the Arabic word meaning “steadfastness,” set out from Barcelona, Tunisia, Italy and Greece.

This week Tunisian vessels joined the mission, pushing eastward to meet Italian and Greek contingents. Soon the boats will converge in international waters as a single convoy, sailing under the banner of non-violent defiance.

Among the more than 150 participants are three South Africans: Mandla Mandela, grandson of Nelson Mandela; social leader Zaheera Soomar, based in the United Arab Emirates; and Cape Town occupational therapist Fatima Hendricks. Mandela has described his participation as a continuation of the global solidarity that once sustained South Africa’s liberation struggle.

A dedicated observer vessel, the Shireen Abu Akleh, named for the Palestinian journalist killed in Jenin in 2022, carries lawyers and peace activists tasked with documenting violations and guarding against distortion.

“We can be those lighthouses to each other in what can feel like a stormy, tempestuous and bleak time for our collective humanity,” said Irish activist Caoimhe Butterly from aboard the vessel.

Pretoria is central to both fronts. Alongside its genocide case at the ICJ, South Africa joined 15 other nations this week in a joint statement backing the flotilla’s humanitarian aims. It warned that unlawful attacks in international waters or detention of participants “will lead to accountability”.

The risks are real: Israel has previously intercepted flotillas in international waters, drawing global condemnation. This time, governments have signalled they are watching.

Together, these developments crystallise a truth Pillay has long advanced: genocide is not just another crime. It imposes duties on every state not only to avoid complicity but to act, to prevent, to punish, to intervene. Neutrality is not a legal option.

For South Africa, the finding sharpens the stakes. Its ICJ case won global respect, but legal argument alone does not halt bombs or open borders. Civil society is already pressing Pretoria to match courtroom leadership with political and economic measures, from sanctions and arms embargoes to reviews of trade ties. Pressure will grow for action beyond words.

It is rare for history to align so neatly: a South African jurist naming genocide in Geneva as South Africans sail toward Gaza. Lawyers aboard the Shireen Abu Akleh prepare to record violations; activists hoist sails under the banner of steadfastness.

Law and solidarity move together. The question now is whether governments will act, or keep looking away. For the moment, South Africans in courtrooms, aboard activist boats and in diplomatic halls have forced the issue squarely onto the world’s agenda. The answer, when it comes, will decide not only Gaza’s fate but the credibility of international law itself, and the meaning of “never again”.