The Corruption Perception Index (CPI) released this week by global anti-corruption watchdog Transparency International delves into the correlation between corruption and insecurity, and ranks states on their performance in 2022.

In the CPI analysis of regional trends, sub-Saharan Africa has once again retained its position as the most corrupt region in the world. The majority of the countries in Africa (precisely 44 out of 49) in this year’s index fall below the midpoint of the CPI scale of 0 (highly corrupt) to 100 (very clean).

The regional average is a paltry 32 against the global average score of 43, indicating endemic corruption in the continent’s public sector. Low-scoring countries (orange and red in the map below) by far outnumbered top-scoring countries in yellow, an indication that African citizens face the tangible effect of corruption on a daily basis.

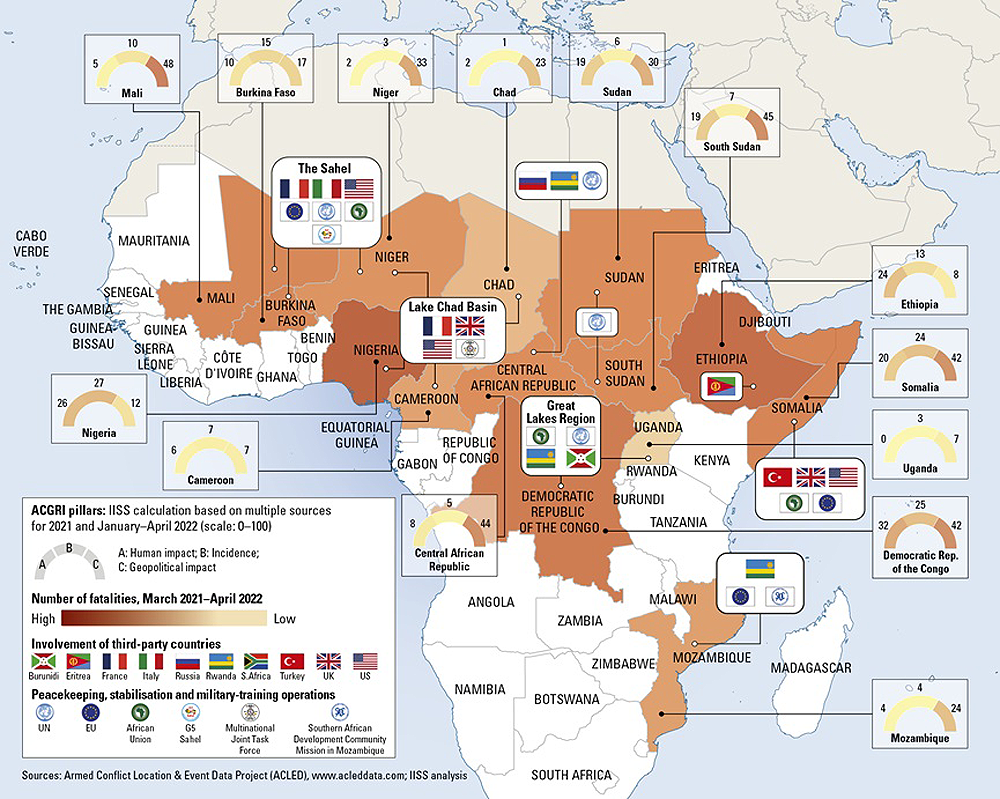

Another survey, this time by the International Institute for Strategic Studies, of the armed conflicts in sub-Saharan Africa provides insights regarding salient regional dynamics of the top 10 countries most affected by conflict and insecurity all in Africa.

A number of coups were staged from 2020 to 2022, with multiple regional and identity-based conflicts taking place elsewhere in the continent. Moreover, the socioeconomic and fiscal fallout of the coronavirus pandemic and the geopolitical and geoeconomic ramifications of the war in Ukraine threaten food security on the continent, further complicating the regional outlook for peace.

When seen through this lens conflicts become one dimensional, when in reality they are a messy and complicated mix of political, social, economic, and cultural factors.

International dimension of African conflicts

Before we condemn Africa as the black sheep of the world, it is important to understand the international dimension of conflicts on the continent and examine Western rationales that drive it.

I have no sympathy for African despots: treasuries are treated as a personal piggy bank, public officials take bribes and elections are rigged. This is publicly known. This opinion acknowledges a strong interface between corruption and conflict. Nonetheless, for a number of reasons, this relationship must be understood within the continuing context of geopolitics.

There is a concerning trend in sub-Saharan Africa of the internationalisation of internal armed conflicts, including civil wars. Over the past decade, the region has become fertile terrain for geopolitical competition among great powers and for further penetration by middle powers.

For instance, 12 so-called internationalised-internal conflicts (civil wars with external intervention by a state) were recorded in the two decades between 1991 and 2010. In the following 11-year period (2011–21), 27 such conflicts were recorded.

Most of these conflicts were recurring. In 2021, there were 17 internationalised civil wars in sub-Saharan Africa — more than twice the number of internal conflicts without external intervention.

Most African states have lost the capacity to decide when they wage or end wars, and recurring rebellion and large-scale banditry now defines a state of chronic instability and insecurity rather than war. And yet wars may be intentionally prolonged by belligerents through corrupt practices related to defence contracts and through corruption.

Need for deeper analysis

That conflict and insecurity can cause corruption is common knowledge. And while the link between African conflicts and international actors is only slowly starting to unravel, it remains less obvious how those states that are involved in conflicts in Africa can maintain their places high on the list of clean countries on indexes such as the CPI.

Western states involved in African conflicts (with the exception of Russia and Turkey already involved in their own conflicts with Ukraine and the Kurds respectively) have earned higher ranking status on the CPI. The United States, United Kingdom, France and Italy were perceived favourably in the CPI.

Some scholars believe the CPI, although presented with an aura of impartiality and ostensibly as an apolitical project, masks a series of deep and abiding controversies and debates relating to the proper place of social and cultural factors in the international anti-corruption industry.

Beyond the controversies and critical discourse of the CPI, the second factor key to understanding the reason Africa is perceived as the most corrupt continent is found in the notion of conflict itself. While this year’s CPI report treats conflict as a time-bound rapture, it does not look at the deep and complex political and historical roots of conflict.

For instance, how the absence of corruption on the rebelling side can foster its capacity and popular support (for example, the Eritrean Tigray People’s Liberation Front at its beginning). Nor does it take into consideration conflict between those enjoying the status quo and those who want reforms.

An example would be the ongoing backlash against French soldiers in Mali and Burkina Faso, which can also be understood as an antidote to corruption given that six decades have passed since most of France’s African colonies gained their independence. And yet France has intervened militarily more than 50 times on the continent, including dispatching troops to protect dictators.

The roots of the conflict lie in the historical argument that economists Adam Smith and Edmund Burke put at the forefront — colonial expansion as the very source of corruption. But also as academic Bartolomé Yun-Casalilla declared as recently as 2021, the early-modern Spanish empire serves as a good case in point: traditionally seen as one of the most corrupt empires of the period, it is argued that — in reality — all empires encountered the same phenomenon in one form or another. It would be useful to have a deeper analysis of conflict, violence and corruption.

Key takeaway

The principal contention of this opinion is that if the dynamics that produced conflict and insecurity in Africa are poorly understood, creating a distorted narrative of the corruption-conflict nexus that relegates the role of international actors to the background, may in turn limit and skew the range of policies imagined to be necessary to address the problem.

Grounding the fight against corruption in such misconceptions would be one way of helping to push the scepticism against corruption measurement indices. And that the leading instrument for asserting the state of corruption or non-corruption, the CPI, should be subjected to scholarly scrutiny, deconstruction and critical analysis. There is an urgent need to decolonise the anti-corruption policy and the so-called anti-corruption industry.

The views expressed are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of the Mail & Guardian.