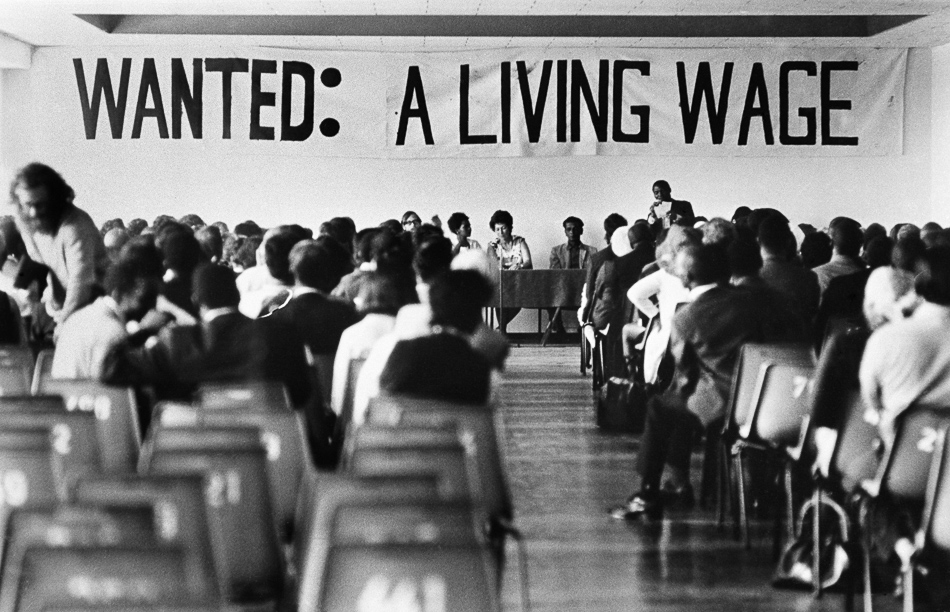

Durban, 1973: Workers at the Consolidated Textile Mill in Jacobs demand a wage hike of R5.

This March, as we commemorate 50 years of the 1973 Durban strikes, we reflect on the National Union of Metalworkers of South Africa’s (Numsa’s) deep roots which lie in the Durban strikes. We are taking this moment to reflect on a general strike by industrial and other workers that began on 9 January 1973.

The year before there had been a strike by dockworkers in Durban, and a new militancy was emerging after the banning of the liberation movement, and the communists, in 1960. When the strikes had come to end late in March 1973, close on 100 000 mainly African workers had come out on strike.

After the 1972 dockworkers’ strikes the General Factory Workers’ Benefit Fund was formed in Durban in 1972 by the radical academic, Richard Turner, trade unionist Harriet Bolton and a number of Turner’s students. Turner was committed to the idea of workers’ control. At the time it was illegal for black workers to belong to a registered trade union, so black workers joined the benefit fund as a cover for trade union activities. After the Durban strikes thousands of workers joined the benefit fund.

Several unions were formed in the wake of the 1973 strikes, including the Metal and Allied Workers’ Union (Mawu), which was founded in Pietermaritzburg in April 1974. It was formed from the benefit fund with 200 members from two factories, Alcon and Scottish Cables. Alpheus Mthethwa was elected as the branch secretary. The Transvaal branch was formed in 1975.

Academic Kally Forrest has written that: “Fierce debate went into the formation of unions like Mawu, and the principles and strategies that emerged underpinned these unions in the future. Central to their strategy was that only an accumulation of worker power could bring meaningful change.

“Richard Turner was assassinated in 1978 showing that the system of racial capitalism saw building workers’ power towards worker control as a serious threat to its existence.”

Mawu was admitted to the International Metalworkers’ Federation. In South Africa it worked closely with the National Union of Motor Assembly and Rubber Workers of South Africa and the United Automobile, Rubber and Allied Workers Union. In 1979 they and other unions formed the Federation of South African Trade Unions (Fosatu).

Fosatu was a workerist union that remained independent from the national liberation movement. Fosatu developed an impressive workers’ culture programme, including poetry and theatre, and was known for its commitment to democratic practices on the shopfloor and for a deep commitment to workers’ control.

Mawu got access to the Dunlop factory in Durban in 1983. The workers began collecting money for a strike fund and then went on a go-slow and a refusal of overtime work. Several workers were fired. There was a major strike in 1984 during which workers adopted the strategy of siyalala la – sleeping inside the workplace at night.

In his autobiography A Working Life: Cruel Beyond Belief, Temba Qabula, who was also a well-known worker poet and playwright, wrote: “We refused to leave because the factory belonged to us. We built it with our sweat and blood. We lost all our energy to this company and so it belonged to us”.

After the strike at Dunlop there were also strikes at Bakers Bread and Clover.

In Praise Poem to Fosatu, first performed in 1984, Qabula, wrote:

You are the metal locomotive that moves on top

Of other metals

The metal that doesn’t bend that was sent to the

Engineers but they couldn’t bend it.

Teach us Fosatu about the past organisations

Before we came.

Tell us about their mistakes so that we may not

Fall foul of such mistakes.

Our hopes lie with you, the Sambane that digs

Holes and sleeps in them, whereas others dig

Holes and leave them.

I say this because you teach a worker to know

What his duties are in his organisation,

And what he is in the community

Lead us Fosatu to where we are eager to go.

There were more strikes in 1985, including stoppages to demand the release of Moses Mayekiso, who had been elected as a Mawu shop steward in 1979 and was arrested in late 1984. He had also been involved in community-based resistance linked to the United Democratic Front (UDF), which was launched in 1983, and the union had become increasingly connected to community struggles.

In 1985, Mawu led a major strike at Sarmcol, a subsidiary of British Tyre and Rubber Company, in Mpophomeni, which is not too far from Pietermaritzburg. Almost a thousand workers were fired. Four members of the shop stewards’ committee were abducted while at a meeting at the home of Phineas Sibiya, a leading Mawu shop steward. Three of them were murdered, the other surviving a gunshot wound. As the strike developed the union came under serious pressure from Inkatha, a generally reactionary and pro-apartheid ethnic nationalist organisation.

Strikers’ meetings

were held in Bolton Hall. Photos: David Hemson Collection, University of Cape Town Libraries

Strikers’ meetings

were held in Bolton Hall. Photos: David Hemson Collection, University of Cape Town Libraries

Also in 1985, members of Mawu in Mpophomeni created a play, The Long March, which told the story of their struggle against Sarmcol. It travelled the world. When the workers called for a boycott of all white-owned stores in Natal (as the province was then called), they came under intense pressure from Inkatha.

In the same year, 1985, Mawu transferred to the new ANC aligned Congress of South African Trade Unions (Cosatu), which was launched on 1 December 1985 with Jay Naidoo elected as the first general secretary. About a third of 460 000 workers who formed Cosatu came from Fosatu, including powerful worker leaders as Chris Dlamini, John Gomomo and Ronald Mofokeng.

In May 1986, Mayekiso was elected as the Mawu general secretary. A month later he was arrested and detained on the charge of treason.

Qabula wrote that Cosatu organised “sleep-in seminars” to educate workers about workplace and community issues and built a fighting federation that took up issues on the shopfloor and the struggle for national liberation.

On May Day in1986 Inkatha launched its own union, the United Workers’ Union of South Africa, carrying a coffin symbolising the death of Cosatu. In Natal there were a number of attacks on Cosatu members by Inkatha. On 6 June, 11 workers lost their lives when a strike at the Hlobane colliery was attacked. But Cosatu became more and more powerful as the struggle against apartheid intensified.

In 1987, at the height of the urban insurrection and the brutal repression meted out under the state of emergency, Mawu merged with three other unions to form Numsa. Those unions were the Motor Industry Combined Workers Union, the National Automobile and Allied Workers Union and the United Metal, Mining and Allied Workers of South Africa. Two Cosatu unions also dissolved into Numsa, namely the General and Allied Workers Union and the Transport and General Workers Union. Mayekiso was elected as the general secretary of the new union while still in detention. He was finally acquitted in April 1989.

The new union remained deeply committed to the principle of workers’ control, and it continued to face severe repression. In May 1989, Jabu Ndlovu, a Numsa shop steward who had previously been a powerful Mawu shop steward, was attacked and killed by Inkatha in her home in Pietermaritzburg. She, her husband Jabulani, also a Numsa member, and their daughter were shot and burnt.

When the ANC was unbanned in 1990 Cosatu openly affiliated to the ANC, as part of what was called the tripartite alliance including the ANC, Cosatu and the South African Communist Party (SACP). Numsa offered critical solidarity with the national liberation movement but took clear positions against the shift to neoliberal policies, beginning with the adoption in 1996 of the self-imposed structural adjustment programme known as the Growth, Employment, and Redistribution plan.

But as the betrayal of the ANC became more and more crude, Numsa’s voice became louder. In November 2014 Numsa was expelled from Cosatu.

Following democratically adopted resolutions the union went on to form a new federation — the South African Federation of Trade Unions — an organisation to link union and community struggles – the United Front and a political instrument for the working class – the Socialist Revolutionary Workers’ Party.

Today Numsa is largest union in South Africa, with more than 300 000 members. It remains committed to fighting hard on the shop floor and has been joined by more and more workers from outside of the union’s historical base among metal workers. Workers in a range of areas — from university cleaners to airline cabin crew — have joined the union, and the union has consistently won benefits for its members. It also remains a revolutionary socialist union committed to building unity among the progressive organisations of the working class, as well as Pan-African and international solidarity.

Irvin Jim is the general secretary of the National Union of Metalworkers of South Africa

The views expressed are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of the Mail & Guardian.