Bheki Cele

2019 – present

President Cyril Ramaphosa, unsurprisingly, didn’t boot ineffectual Police Minister Bheki Cele out of his cabinet in this week’s reshuffle.

The voting bloc Cele has delivered to Ramaphosa to ensure his ascension to, and subsequent retention of, the ANC presidency has apparently made the former schoolteacher from KwaZulu-Natal politically untouchable.

Cele’s continued presence in the cabinet is confirmation that the ANC, as governing party, is unconcerned about making South Africa a more equal society that is safe and prosperous.

The changes made by Ramaphosa to his cabinet. Police Minister Bheki Cele survived. (Compiled by Lineo Leteba)

The changes made by Ramaphosa to his cabinet. Police Minister Bheki Cele survived. (Compiled by Lineo Leteba)

It reflects a factionally-motivated retention of mediocrity and failure which is pervasive in government. This incapacitates the ANC’s responses to the crises that are wrecking faith in the rule of law and threatening to break democracy — whether these be unemployment, substance abuse among the youth or climate change.

For South Africans facing the daily prospect of rising violent robbery, rape and murder this governing incapacity is clearest in our lack of safety.

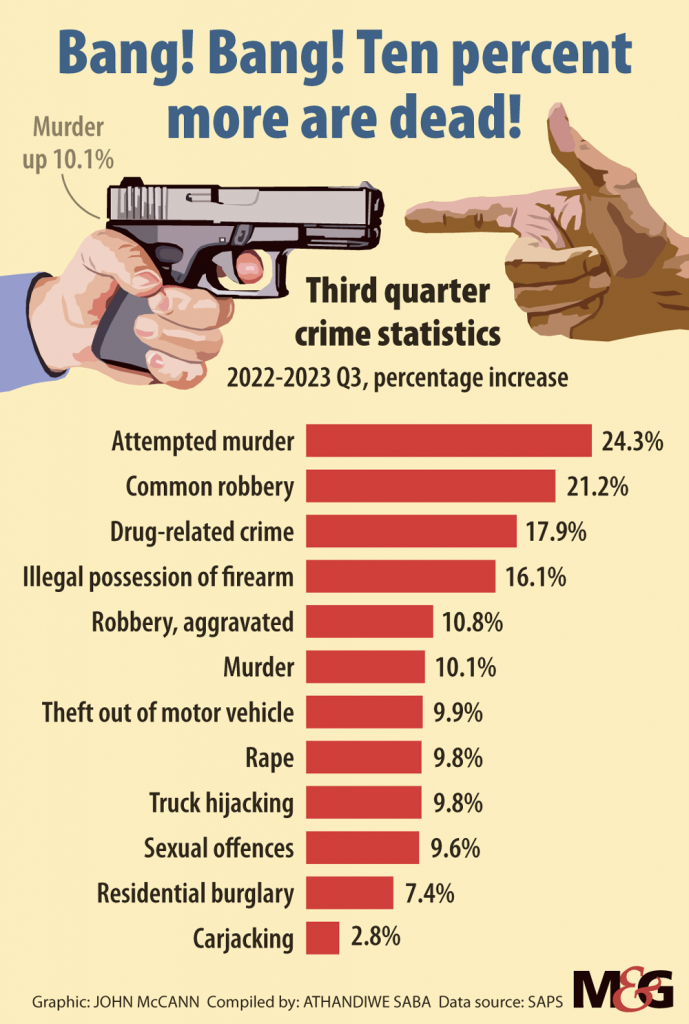

The crime statistics are as astonishing as they are trite.

Over the past decade murder has increased from 15 554 deaths in 2011‑12 to 25 181 in 2021-22. An increase of 63%. Let that sink in. Almost 10 000 more people were murdered last year compared to a decade ago. That is almost 26 more people being murdered every day compared to 10 years ago.

South African police carry out a large-scale operation in the Westbury area of ââthe city of Johannesburg, where crime has increased recently, on March 8, 2023. Some citizens are detained during the operation. (Photo by Ihsaan Haffejee/Anadolu Agency via Getty Images)

South African police carry out a large-scale operation in the Westbury area of ââthe city of Johannesburg, where crime has increased recently, on March 8, 2023. Some citizens are detained during the operation. (Photo by Ihsaan Haffejee/Anadolu Agency via Getty Images)

Gareth Newham, of the Institute for Security Studies, said the government does not have a dedicated murder reduction strategy. There is “no document in government”, whether in the police ministry or the police service, to respond to the year-on-year increase in murder since 2012.

Newham was talking at a recent panel discussion about South Africa’s security crisis.

Other crime statistics are staggering. While the budget for the police grew by 72% from R58 billion in 2012 to the current R100 billion in the financial year ending on 28 February, their ability to solve crime has diminished by 55%. In 2012 police solved 31% of the murders reported to them but last year it was a meagre 14.5% of the murders.

It is also depressing to consider that the police are so bereft of investigative, evidence gathering and forensic skills that 90% of armed robbery cases never reach the point of being prosecutable. Nine out of 10 times, armed robbers won’t even appear in the dock.

The figures also point to an escalation of police corruption, criminality, brutality and torture.

In the past five years police have paid out R2.3 billion to victims of unlawful police conduct — proven in our courts. This amount is 52% higher than the previous five years.

Yet Cele, speaking after Ramaphosa’s recent State of the Nation address, suggested that more boots on the ground would help solve the country’s rampant crime problem. Cele talked up the 10 000 police trained and introduced into the service last year and the prospect of repeating it in 2023.

But we already have 180 000 cops who appear to be doing very little aside from drawing a salary — and the occasional bribe.

Cele’s antidote merely touts quantity over quality.

It certainly does not consider how many police, from the generals all the way down to the constables, increasingly believe their jobs are guided by politics rather than policing best practice.

Evidence presented to the Farlam commission of inquiry into the 2012 Marikana massacre (when police killed 34 striking mineworkers) confirmed that in deciding to use live ammunition to resolve the wildcat strike at Lonmin’s platinum-mining operation, leaders such as then North West police commissioner Lieutenant General Zukiswa Mbombo and national police commissioner Riah Phiyega were more considerate of political issues rather than policing ones.

(John McCann/M&G)

(John McCann/M&G)

Cops I spoke to in KwaZulu-Natal said the disappearance of police and police leadership during the 2021 July riots, which were orchestrated and manipulated by factions in the ANC and organised criminal elements — both with alleged ties to former president Jacob Zuma — was down to two things.

First, police leadership with links to those factions who believed their job was to protect the interests of that faction rather than citizens.

Second, others in command who “ran away because they are afraid to make policing decisions” — a leadership deficit brought about by their being prematurely promoted beyond their abilities, according to my sources.

The 2012 National Development Plan bears these testimonies out, describing “serial crises of top management” in the police. It is a leadership deficit among the generals that persists to this day because recommendations from various commissions of inquiry continue to be ignored.

The ANC’s factional politics has seeped into how the police think, act and react.

Police independence and efficacy has also been undermined by that politics: crime intelligence is used to spy on comrades rather than for infiltrating criminal networks and preventing crimes before they happen. It’s a trend that is now rampant, but started during the Thabo Mbeki presidency.

One ANC leader at the panel discussion, who has previously held safety and security portfolios but cannot be named because of Chatham House rules, didn’t mince their words.

“How do you fight crime without crime intelligence — and we [the ANC] were the ones who degraded the crime intelligence structures, let’s be frank about that — and so I don’t know what kind of crime intelligence structures we have in place now, I don’t know.”

Perhaps the most depressing aspect of this gross ineptitude and lack of will for ordinary people staring down the barrel of an assailant’s gun is that the crime tide can be turned back.

It has been done before. In the first 18 years of democracy South Africa’s murder rate dropped by 56%. By analysing data that provides a granular geographical breakdown of the type and pervasiveness of criminal activity and making focused policing interventions, crime can be reduced.

According to another speaker at the panel discussion, Gauteng managed, in two years, to reduce car hijackings by 32%. This was mainly through focused intelligence-gathering and forensic investigations targeting hijacking hot-spots in the province. Since 2012 car hijackings in Gauteng have ballooned by 122%.

Political will leads to policing will. Especially if there is a non-factional attempt to reform the police service, clean out many underperforming and self-serving generals and build the South African Police Service’s investigative and intelligence-gathering skills sets.

This is unlikely to happen anytime soon. Cele, like many ministers at national and provincial level, imagines his job with celebrity flair. To quickly flag down a private jet, head to some high-profile crime that has outraged the nation, and to be seen on television.

Cele will continue to deliver empty promises with a bombast and bluster more annoying than the Cape Doctor persistently gusting through Cape Town.

Ramaphosa will continue to mouth platitudes about action and accountability while his government does little.

Meanwhile, people, in ever increasing numbers, will continue to mourn out of earshot of the ineffectual and callous state — unless there are television cameras nearby.

Niren Tolsi is a freelance journalist whose interests include social justice, citizen mobilisation and state violence, and protest. He has written extensively about the Marikana massacre and policing.

The Public Affairs Research Institute commissioned Tolsi to respond to a panel discussion. The views expressed are his own.