Social media has become a theatre for violence and intimidation, particularly where gang affiliation is concerned.

The Fourth Industrial Revolution (4IR) has revolutionised the banking sector by eliminating the need to visit the bank for transactions, deposits and inquiries. Long queues have become a thing of the past, because people can, with a few clicks, use banking services.

But the South African Reserve Bank has identified cybercrime and emerging technologies as a threat to the country’s banking sector, despite the recent signing of the Cybersecurity Act of 2021, which holds financial institutions accountable for cybersecurity attacks and financial breaches.

Information technology services company Accenture estimates that South Africa loses $127 million annually to cybercrime, and the country experiences the highest number of targeted ransomwares attempts in Africa. According to the South African Banking Risk Information Centre, the big five banks account for 20% of reported online incidents, which leads to 45% of gross losses annually.

To address this issue, stronger cybersecurity measures, improved risk management strategies and increased collaboration among stakeholders are needed to mitigate the threats associated with emerging technologies in the banking sector.

The main concerns for the banking sector are security and privacy, perceived trust, perceived risk and website usability.

How the banking system becomes a crime scene

In less than a decade, the development and use of the internet has become an essential element of modern life. Like other aspects of globalisation, the expansion of 4IR with the internet has far exceeded regulatory capacity, and the absence of such authority has left room for abuses to occur. This issue is compounded by its design; the internet is fashioned on a military system to circumvent interferences and external controls. But even with those who are famously championing for its creative anarchy, many have come to realise that the internet and influence of 4IR can increase the level of crime that already exists in South Africa.

The term “cybercrime” describes a range of offences, including offences against computer data and systems (such as hacking), computer-related forgery and fraud (such as phishing). According to an Interpol cyber security report, South Africa has seen a 100% increase in mobile banking application fraud and is estimated to suffer 577 malware attacks an hour, each day. Accenture estimates that South Africa is losing $127 million a year to cybercrime and has the highest number of targeted ransomware attempts in Africa.

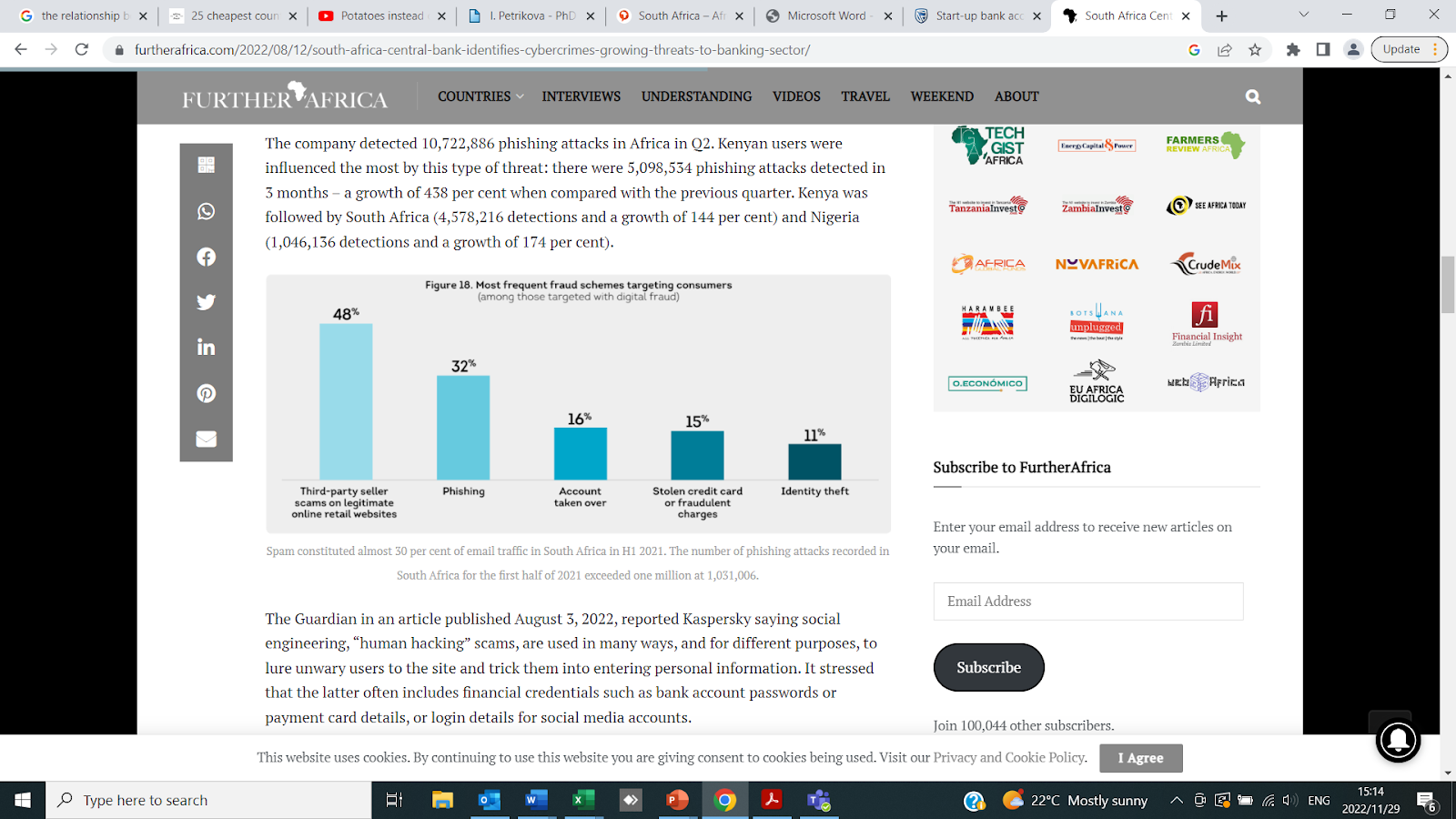

Figure 1: The most frequent fraud schemes targeting consumers.

Source: Ajibade, P. and Mutula, S.M., 2020. Big data, 4IR and electronic banking and banking systems applications in South Africa and Nigeria. Banks and Bank Systems, 15(2), p.187.

Cybercrime has evolved from mischievous one-upmanship of cyber-vandals to a number of profit-making criminal enterprises that haunt customers at the four major banks — Standard Bank, First National Bank, Absa and Capitec. Criminals, like everyone else, have access to the internet for effective communication and information gathering, and this is facilitated with a great number of traditional organised criminal activities.

First, it is now more often that software tools are purchased online that allow the users to locate open ports or overcome password protection. This accessibility expands the pool of potential offenders beyond expert hackers and coders, allowing individuals with easy access to such programs to become involved in cybercrime. The development of “Mariposa” is a fitting example of this, a network of enslaved computers used by cyberthieves for spying and spamming. In the case of banks, compromising their systems or customer accounts can lead to severe data breaches, exposing sensitive information such as account numbers, passwords and personal details. Compromised passwords can also enable unauthorised fund transfers or facilitate the unauthorised acquisition of short-term loans through easily accessible loan authentication methods.

Second, a bank account can easily be taken over. With control of a bank app or infected computers, cybercriminals can potentially gain unauthorised access to bank accounts that can result in fraudulent transactions, fund transfers or a complete takeover of customer accounts.

Third, the flexibility of technology allows for “malware attacks” to transpire. For instance, cyberthieves create malicious programs which can infect bank employees’ computers or customers’ devices, compromising their security and facilitating unauthorised access to banking systems or stealing login credentials. Businesstech notes that about 48 000 login credentials are stolen annually, with cyberthieves even targeting customer fingerprints. Moreover, the research has uncovered 81 000 stolen digital fingerprints in analysed markets.

In some cases, the risk management departments of banks may have time to assist clients in investigating stolen credentials. This delay often results in customers becoming victims of unaccepted cases, leading to the loss of their funds. Processes beyond the control of allocated investigators, frequent inquiries from victims, and dubious fraud claims that result in chargebacks contribute to the difficulty in uncovering the essence of the crimes. In 2022, only about 23% of cases were resolved in favour of the customer.

The Ombudsman for Banking Service has noted a 7% increase in cybercrime complaints since 2020, indicating an overall rise in such incidents. The Broadband report reveals changes in the number of cases reported by South Africa’s top four banks:

- Nedbank and Capitec experienced the largest increases in complaints, at 18% (1 273 in 2021 to 1 508 in 2022) and 11% (1 651 to 1 826) respectively;

- Standard Bank witnessed a 31% decrease (2 070 to 1 385), while FNB had a 21% decrease (1 452 to 1 147); and

- Absa had the lowest number of cases among the major banks and remained at the same level (1 068 in 2022 compared to 1 063 in 2021).

In addition, there was a 3% rise in digital banking complaints, constituting 17% of the total grievances. Specifically, mobile banking fraud and vishing (voice phishing) were identified as the major types of complaints. Vishing is when fraudsters contact customers through phone calls or voicemails, pretending to be from a trustworthy company, with the intention of acquiring sensitive information such as bank account details and credit card numbers.

Recommendations

Nearly 500 000 individuals face daily cybersecurity threats. The losses incurred in this modern era of banking exceed those experienced during the time when traditional banking practices were the norm. Without the expansion of technology in the banking sector, there can be no socio-economic growth, and African states will struggle to achieve a technological advantage on the international stage.

It is essential for regulators and financial institutions to take proactive measures to combat financial criminal activities. These measures may include the implementation of robust anti-money laundering and “know your customer” procedures, the enhancement of cybersecurity measures, regular audits and internal controls, and the cultivation of a strong ethical culture in banks.

Moreover, effective collaboration between banks, cybersecurity firms, law enforcement agencies and regulatory bodies to share threat intelligence, best practices and incident response strategies is crucial for the detection and prevention of financial crimes. By working together, these stakeholders can improve the security and integrity of the banking system.

It is necessary to identify and analyse the security risks associated with 4IR technologies in the banking industry. This includes a comprehensive examination of cyberattacks, data breaches and the potential for human error. Understanding these risks is essential for developing effective security strategies.

Banks can also make use of multi-factor authentication, as well as continuous monitoring to enhance their security measures and safeguard against potential threats.

It is equally important to educate employees and customers about the evolving risks and best practices to mitigate cyber threats.

Nomzamo Gondwe is a research associate with the 4IR and Digital Policy Research Unit at the University of Johannesburg.