'Arrive Alive'. A man keeps warm under a flyover in downtown Johannesburg. Photos: David Edwards

Knowing I can go onto Facebook each day and find at least one new David Edwards photo is one of life’s enduring pleasures. I’m not sure why, because his subject matter is the grime, squalor and urban decay that Joburg’s city centre and its immediate suburbs — Troyeville, Bertrams, Bez Valley, Yeoville — have become.

A mother provides shade. Kensington.

A mother provides shade. Kensington.

Perhaps it’s because, as fellow photographer Gabrielle Ozynski puts it: “David’s photos reveal humanity in areas that are often avoided and despised. His subject matter is so familiar and often rather dismal. Most would not bother to photograph it. A person crossing the road — well, how dull. People having a chat on the pavement next to a spaza shop. Yawn. Infrastructure crumbling — sigh. But then, few are able to take the kind of photographs David takes. His composition, use of light, sensitive portrayal and often witty observations lift his pictures into another realm.”

Shelter with post-modern décor and a bath full of rubbish. Ellis Park.

Shelter with post-modern décor and a bath full of rubbish. Ellis Park.

Jonathon Rees, another photographer, says: “David is doing important work with his brave forays to capture the grim beauty of Jo’burg’s collapsing infrastructure. His images are bleak and unvarnished portrayals of urban political tragedy, yet still shine with David’s own warmth and acute sense of history. There are abundant dangers in stopping to shoot the vandalised and neglected city; but he’s tirelessly in there, getting close to the grit and grime, telling stories of the ruin he recognises and appreciates as a social and visual historian.”

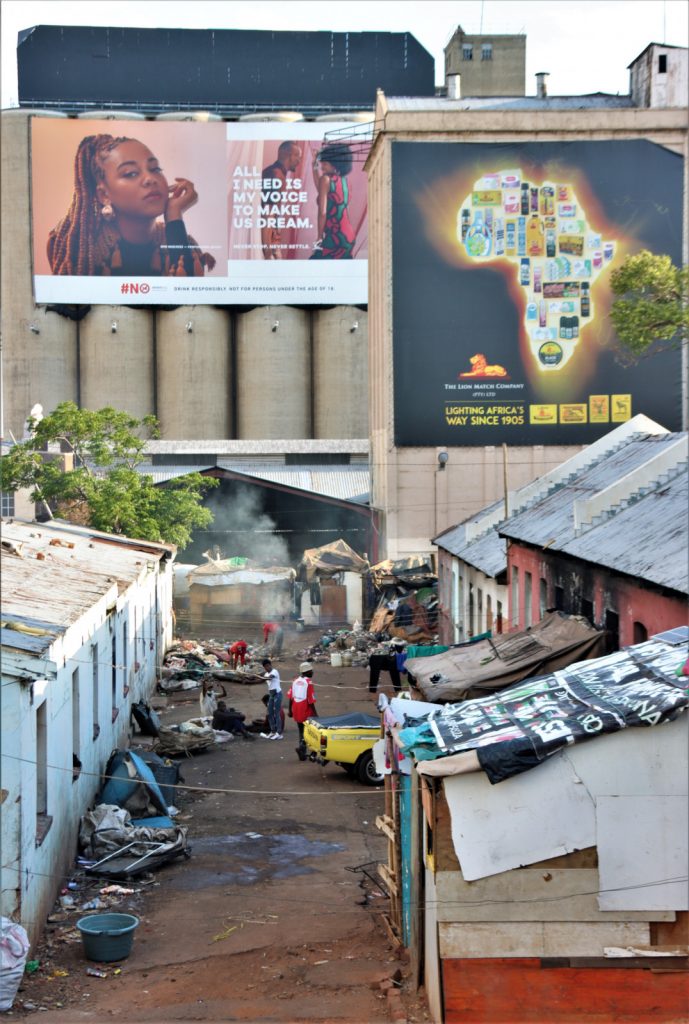

Dreams and Realities. The illusion that individual self-expression will save all of us.

Dreams and Realities. The illusion that individual self-expression will save all of us.

Why Edwards shoots what he does

Edwards grew up in a number of places, including Yeoville, Springs and Polokwane (then Pietersburg). His interest in the past was piqued by a history teacher at Pretoria Boys High School, dubbed Fifi by the lads, some of whom — including Edwards — would bunk from boarding school and travel to the “liberated zone” of Hillbrow.

The sun sets on the Promised Land.

The sun sets on the Promised Land.

He then moved to the Reef and from there to the platteland, which was “conservative but physically beautiful”, where he took up photography, which was “always about the beauty of the land and animals. It is a frame of reference which I have carried with me”.

At the University of the Witwatersrand, where he studied history and English, he met a new generation of radical historians, and “went to seminars on [Jacques] Lacan and fantasised about the marriage of Marx and Freud”. Initially convinced that revolutions were a good thing, after 1994 he soon realised that the slogans of mobilisation “bore no relation to the ANC in power” and, disillusioned, took up training black managers all over Africa, particularly in Tanzania, Ghana and Zambia.

Luxor Mansions. Layers of occupation. Bertrams.

Luxor Mansions. Layers of occupation. Bertrams.

“My love of history informs the way I see the CBD of Jo’burg, which looks like an entropic ruin, a fallen empire abandoned by power and wealth,” says Edwards. “Its dereliction coincided with the flight of the rich to Sandton. The architecture stalled in the seventies, got temporarily boosted by the banks and mining houses, and then transformed itself into a fascinating African city in which buildings are hijacked by gangsters and [where] people bring up their children and do their washing.”

Alone on End Street.

Alone on End Street.

He’s chosen to share his images on Facebook because he feels it cultivates intelligent feedback, which tests his vision. “People are sometimes dismayed by my unflinching photos of town and by my war between the search for beauty and the reality of homelessness and poverty. My pictures do not celebrate suffering, they show people struggling to survive in a hostile place; ordinary people scratching out a living on the margins of late capitalism. [Jo’burg is] a city betrayed by another fake revolution.”

The difficulty of being an ‘objective’ photographer

Sometimes Edwards adds captions to his Facebook photos, which provide a glimpse of what he’s feeling when he’s shooting. Here’s an example of how he felt while shooting a man sifting through garbage in an attempt to find something of value.

Resilience in adversity. Troeville/Fairview boundary. Respect

Resilience in adversity. Troeville/Fairview boundary. Respect

“Resilience in an indifferent society. Structural poverty. Foraging in a world stacked against the poor. This is not about bad habits or lack of effort. This is about capitalism in a post-colony. An economic system where we strive to out-compete each other. It’s also about a failure to govern and manage our resources. Not exactly a better life for all.

“Heaven and hell are a few blocks from each other. Getting the crown jewels back isn’t going to change this. These recyclers are scratching out a living. The state has abandoned them.

“You may not want to see it, but more and more of us live like this. If you think this photo violates human dignity, you have missed the point. Our society violates human dignity. It has for a long time now.”

Zulus, Zamaleks and the ‘soft white man’

Other shoots turn out more positively; on this shoot, there was some interaction between himself and the Zulu, beer-drinking subjects of his lens.

The roof of Esigodi Phola Homes on a Sunday night.

The roof of Esigodi Phola Homes on a Sunday night.

“There are Zulus on the roof drinking beer

says the night watchman.

Here’s twenty bucks I reply

Will you keep an eye on my car?

The light is perfect.

I shout loud greeting as I emerge onto the roof

into the glorious summer light

and then

mind my own business and start taking photos

of the light reflecting off Commissioner Street below.

I am peering through the lens when

I sense someone behind me.

My gut drops and I imagine some bad person

is about to grab my camera and toss me over the parapet.

I step back from the edge with a sharp sense of vertigo.

Hullo, says a man with a magnificent smile

Will you take my picture?

I am Emanuel.

My breathing returns to normal.

Sure, I say.

He wants the skyline in the picture, but I explain

that the sunset will drain the colour out of the image.

I need to show my girlfriend how beautiful Joburg is, he says.

He cajoles his friends into the frame.

Will you drink a Zamalek with us? he asks.

This is turning out well.

We chat and he says you are a soft white man.

That’s good, he says.

Hard white men are not nice.

I am quietly pleased and I drink my beer.

He offers me another and I’m about to explain

that I must go home to wash the dishes and cook dinner

for my wife and daughter

before the load-shedding kicks in

but I figure I will look ridiculous

to these guys with their large biceps.

I thank them somewhat too profusely

and take my leave.

As I walk down the stairs

I feel happiness and a hint of grace welling up

in the inky darkness of the stairwell

and then a sense of gratitude.

I realise when I get to my car that

I have tears in my eyes.

When I get home,

two lusty souls are are enjoying sexual congress

against my garage door.

His pants are around his ankles;

She looks flushed.

I turn off the headlights

to afford them some dignity

as they vanish into the night.

How Edwards gets his shots

Curious about the story behind Edwards and his inner-city shoots, I asked him what the process entails. His brief answers are Hemingwayesque: direct, laconic, gritty. I elected to leave them in his style, as I felt that to summarise them in my own words would not do them justice.

Football. Belgravia.

Football. Belgravia.

When did you start shooting Jo’burg?

I started taking photos of Johannesburg and the Reef four years ago. I had spent many years facilitating adult learning all over Africa and, when I retired, I needed a project that would give my life more shape and some excitement. A friend encouraged me to accompany him on early-morning drives to explore “town” and the reef.

Carnal negotiations on End Street at dawn.

Carnal negotiations on End Street at dawn.

What was your motivation?

I was motivated to find better ways of looking at the city I have lived in. I was born here at the Florence Nightingale Hospital in Hillbrow in 1955. My earliest memories include taking a trolley bus over the Queen Elizabeth bridge and walking down Cavendish Street to Scotch Corner from Westminster Mansions. When I taught in Sandton, I lived in Bez Valley. I still live at the Troyeville end of Kensington.

I prefer the south to the north. Its layers of habitation elicit a sense of duration. It has texture. The northern suburbs amount to the “geography of nowhere”. I would rather live in Africa. When I have taken photos of Sandton they end up looking like company reports. I hope my pictures are truthful and reflect the human condition across more realms than the sanitised and hermetically sealed north generally permits. This is a view from the south.

A place in the sun. Hillbrow.

A place in the sun. Hillbrow.

I have always believed photographs involved a search for beauty. This may sound unlikely. The south speaks to the stamina and resilience of ordinary people. Joburg chews up migrants and spits them out. People are engaged in everyday survival.

What camera gear are you using?

I started out using a cheap Canon 2000D and a secondhand 55 to 250mm zoom lens. I enjoy using a 10 to 20mm wide angle. It’s great for cramped conditions, like shooting out of a car window. I spoiled myself recently and bought a Canon 90D and an 18 to 300mm lens. It means I don’t have to change lenses in dodgy places and its flexibility stops the camera from getting dirty in the innocuous Food Lovers bag I carry it in. It’s heavy and can also be used as a cosh. I use a beanbag to stabilise the camera when I need to.

Broken pipes. Yeoville seen from Louis Botha Avenue.

Broken pipes. Yeoville seen from Louis Botha Avenue.

What is the general reaction from your subjects?

I negotiate with people when I take portraits. In an age of selfies, people are used to having their pictures taken. Many people ask. Others don’t want their photos taken. I respect that. Occasionally people get angry and threaten to kill me. There’s generally a reason, like illegal occupation of a hijacked building. Recently, I took a picture of a pregnant pitbull in Troyeville which was supplying fodder for dogfights, and the owner wanted to avoid exposure. Things got nasty.

Children in Bez Valley.

Children in Bez Valley.

Have you been in any dangerous situations while shooting?

I try to avoid danger by shooting very early on Sunday morning when I think potential assailants are still asleep or from secure rooftops. I prefer shooting with a getaway driver. I like having someone to cover my back. I enjoy the rush of being in dangerous places. I’ve been lucky so far. This is South Africa. I am not inclined to simply cower in my house waiting to be murdered in a home invasion.

Stamina. Recyclers setting out on a rainy morning. Hillbrow.

Stamina. Recyclers setting out on a rainy morning. Hillbrow.

Do you work on your photos after you shoot them?

Sometimes there is an obvious conflict between aesthetic form and gritty content. It creates dissonance and can make pictures interesting. Ugliness can also be appealing. It is all about the light. I used to enjoy juicing the colour digitally when I moved from analogue, but now I don’t use filters and rely on the quality of what’s there. I had a friend who was pretty direct in telling me when I was out of line. Reality is enough. I have had the good fortune to get feedback from some fine photographers. I don’t use artificial light. The way photographs are currently manipulated to look like hallucinations feels somewhat obscene.

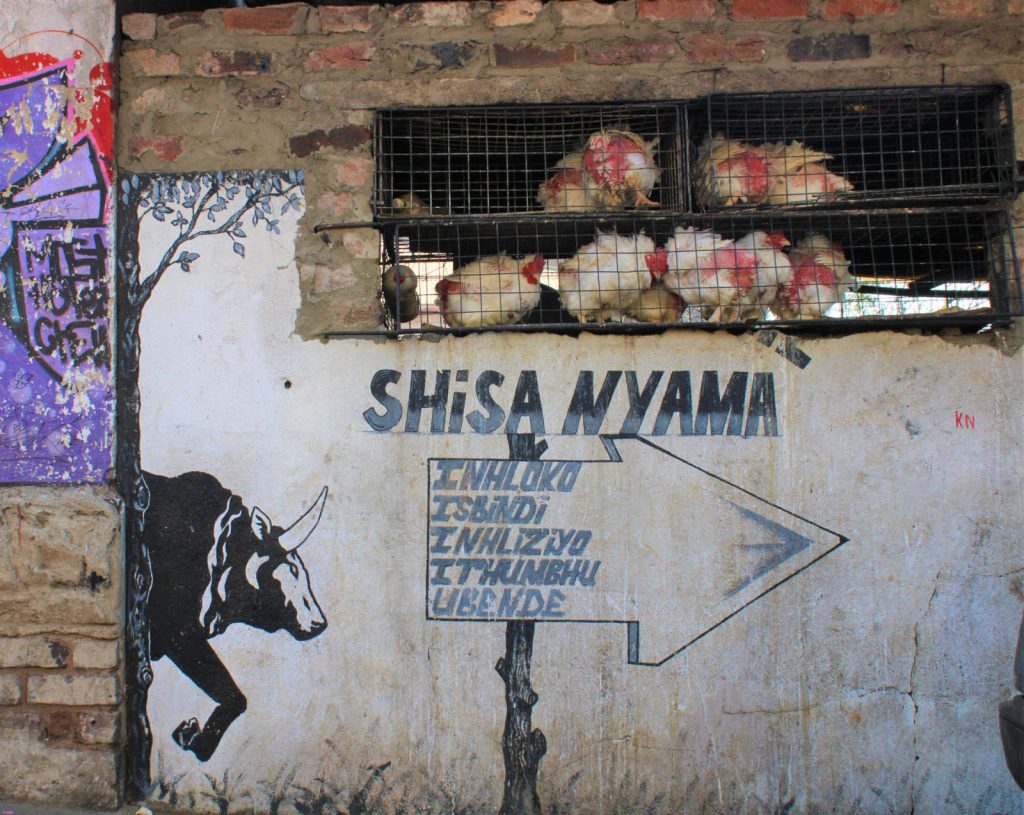

Fresh Chickens. Judith’s Paarl.

Fresh Chickens. Judith’s Paarl.

Who is your intended audience?

My intended audience is mainly other South Africans and people who are curious about how our world has changed. I don’t judge what I see. Part of my interest is to chronicle the re-purposing and re-invigorating of this vibrant, cosmopolitan city. I also like shocking people in shared security cluster villages out of their sense that they are living in California. As an historian, I tend to treat the world as evidence and take the long view. The present feels like the end of an oppressive empire and a descent into chaos. It is not the first time this has happened. We are not unique.

Devotions. Shembe devotees dancing outside the defunct Fairview Fire Station.

Devotions. Shembe devotees dancing outside the defunct Fairview Fire Station.

Who are your influences?

My most important influences are Ivan Vladislavic’s ruminations like Portrait with Keys and Italo Calvino’s Invisible Cities. I find deep resonance with JG Ballard’s dystopian visions and enjoy the work of observational realist painters such as Willem Pretorius and Walter Meyer. Hermann Niebuhr’s paintings of the foyers of flats in town and Yeoville remain a benchmark. Obviously, the gigantic presence of David Goldblatt has conditioned many of us to see South Africa in a particular way. He was the master.

Exuberance. Sunrise in Judith’s Paarl.

Exuberance. Sunrise in Judith’s Paarl.

Edwards has had an exhibition, which focused on derelict, unused railway stations. Despite the squalid subject matter, he managed to cover his costs. He’s creating a website on which to place his photographs. Meantime, you can see his shots on Facebook.

Derek Davey is a sub-editor in the Mail & Guardian’s supplements department who occasionally puts pen to paper. He has irons in many metaphysical fires – music, mantras, mortality and moustaches.