Rising interest rates and living costs deal a double blow to the poor. (Photo by MARCO LONGARI / AFP)

Last month, the South African Reserve Bank raised interest rates by 75 basis points, thereby increasing the prime lending rate to 10.5%. This was due to third-quarter inflation remaining high at 7.6% and outside the target range of 3% to 6%.

This was the seventh consecutive hike, resulting in a cumulative raise of 350 basis points since the hiking cycle began last November. It is thus encouraging that the bank is forecasting a moderation in headline inflation, with a full-year forecast of 5.4% and 4.5% for 2023 and 2024, respectively.

Specifically, while the 2023 first-quarter inflation rate is expected to be 6.8%, this begins to taper off in the second quarter, with a forecast of 6%, moderating further to 4.4% in the third quarter.

The lower inflation rate forecasts signal a potential pause in the hiking cycle in the future, as the inflation rate begins to move within the target range. Although this would provide consumers with much-needed respite, it might be a little too late for some.

Two institutions are critical to this discussion because of their major role in South Africa’s financial system — the Financial Sector Conduct Authority (FSCA), established in 2018, and the National Credit Regulator (NCR), formed in 2006.

The FSCA’s mandate is to “enhance the efficiency and integrity of financial markets; promote fair customer treatment by financial institutions; provide financial education and promote financial literacy; and assist in maintaining financial stability”.

The NCR’s mission is to “support the social and economic advancement of South Africa by regulating for a fair and non-discriminatory marketplace for access to consumer credit; and promoting responsible credit granting and credit use, and effective redress”.

In its April 2022 outlook report, the FSCA highlighted that South African consumers were heavily indebted, with more than 50% of South Africa’s credit-active consumers over-indebted. Given the trajectory of interest rates since then, consumer over-indebtedness has possibly worsened.

In fact, the NCR’s June 2022 quarter consumer credit report shows a higher rejection rate of 66.7% for new credit applications. This compares with 66.04% in December 2021 and 66.4% in March this year.

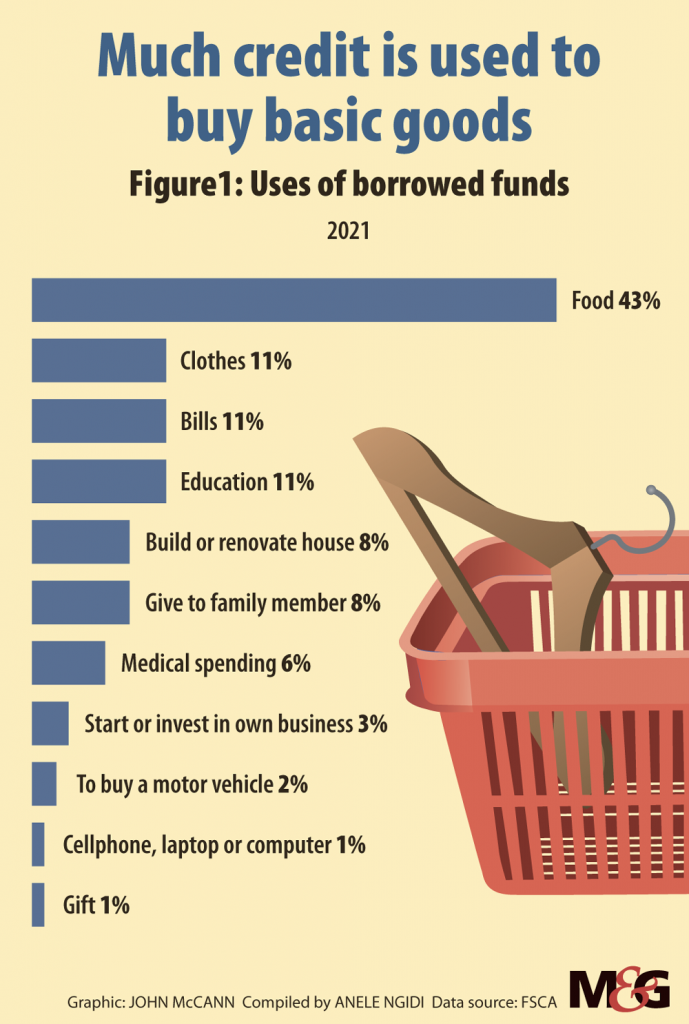

Higher rejection rates indicate that consumers are still trying to access more credit but are deemed uncreditworthy. Typically, this is due to consumers either being over-indebted or showing a poor ability to keep up with monthly instalments. The FSCA’s report also showed that 54% of the borrowed funds were used to fund basic needs.

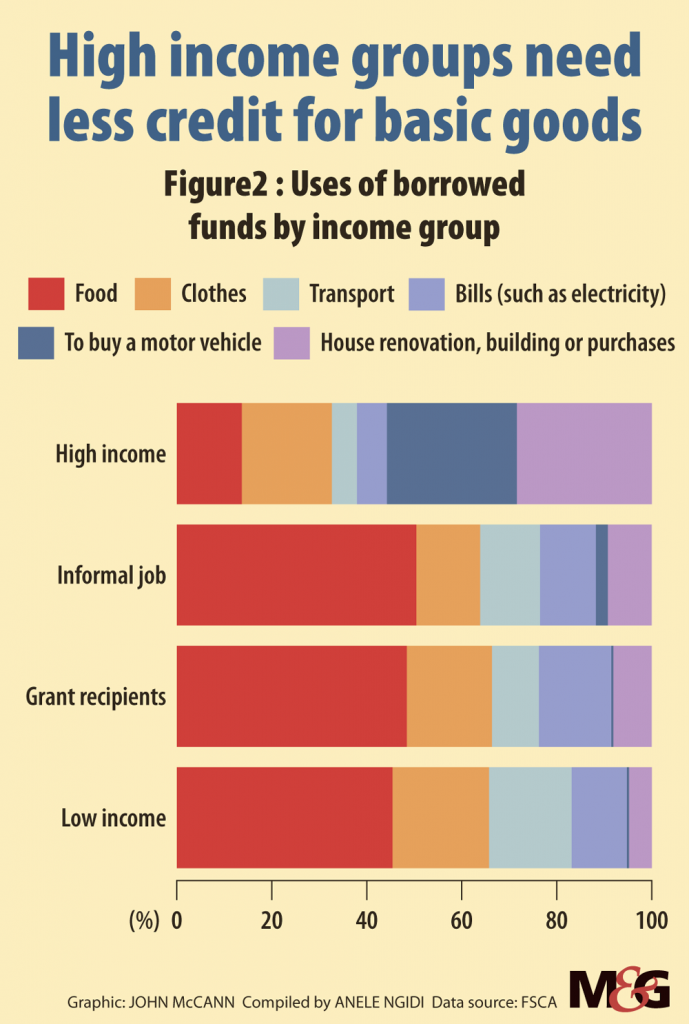

But who are these customers? Sadly, this was more prevalent in lower-income groups (earning less than R1 500 per month), grant recipients (earning about R1 500 per month), and individuals with informal jobs (earning more than R1 500, but less than R3 000).

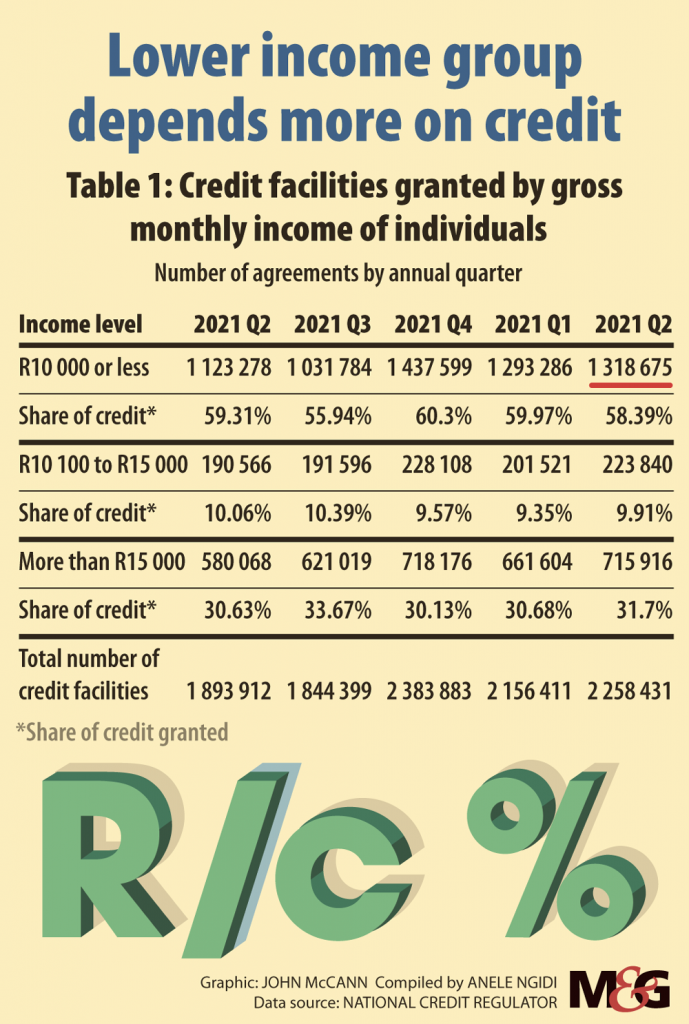

And as table 1 shows, it is also the same groups earning less than R10 000 that constitute the highest number of credit facilities at just more than 58% in the second quarter of 2022.

This raises an important point regarding the real cost of these basic needs for this category. The real cost of these basic needs is not just inflation, but rather, inflation plus the higher interest rate. Therefore, as servicing debt becomes increasingly hard due to the higher interest rates, what happens to the ability of these groups to access these basic needs?

When we see a moderation in the share of credit facilities being extended to these groups and high rejection rates, should we celebrate or be concerned? This is especially so when knowing that inflation has continued to rise, thus shrinking the value of the already limited financial resources they might still be able to access.

As it is, the November household affordability index as reported by the Pietermaritzburg Economic Justice & Dignity Group estimates the cost of a basic nutritious diet for a household of four at R3 287.44 a month. This is more than twice the monthly income of some of these low-income groups.

Certainly, restricting credit to those with too much debt that they cannot service is prudent and in line with the objectives of the NCR. But when people cannot feed or clothe themselves, what gives?

When one of the objectives of the FSCA is to monitor the extent to which the financial system is delivering fair outcomes for financial customers, is it fair that the poorest members of society are spending even more on basics such as food?

You can educate people on responsible debt use, but it becomes meaningless when people are hungry. To the privileged, using debt to fund such basics defies logic and could even be seen as irresponsible. But is it?

Using debt to finance these needs is not ideal. Neither is it sustainable. Yet, there are bigger urgent challenges of sustainability and holistic social responsibility issues we must collectively address.

Given South Africa’s high unemployment rates, it is most likely that those fortunate enough to be employed are compelled by myriad factors to be trapped in a vicious credit cycle to help support their families. The idea of “family”I am talking about often extends beyond immediate family members.

If one looks at the black African population as a previously financially excluded group, the expanded unemployment rate is more than 47%. On top of that, the Pietermaritzburg Economic Justice & Dignity Group estimates that for this population the average salary for November based on the national minimum wage was R4 081.44.

Since this salary often supports 4.2 individuals, that results in an income per person of R971.77, which is below the upper bound of the poverty line of R1 417. So, if basic food alone costs more than R3 000, how are the other needs meant to be funded?

Clearly, the issue of excessively high reliance on debt is complex and there are no easy answers. This conundrum requires urgent discussion in the broader context of making South Africa a more humane and habitable place, especially for the poorest members of our society.

Anele Ngidi has many years of experience in the stockbroking and asset management sectors in South Africa. She is passionate about sustainability and socioeconomic justice, especially for black women and the rural poor. You can follow her on Twitter at @Ng_anele.

The views expressed are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of the Mail & Guardian.