The Biden administration failed to fix the latency that exists in the executive leadership and public strategic planning of the US Mission to South Africa. (Photo by Drew Angerer/Getty Images)

The US Mission to South Africa presents an important case study on the extent to which the Biden administration has followed through on its commitment to chart a fundamentally different course for American foreign policy. The Biden administration may have outperformed the Trump administration when it comes to the length of time that it took to both nominate a US ambassador to South Africa and publish an Integrated Country Strategy for South Africa. But, the Biden administration failed to fix the latency that exists in the executive leadership and public strategic planning of the US Mission to South Africa.

Its inability to correct these known issues is problematic for American foreign policy. Among other things, they undermine the performance, accountability and authority of US diplomatic missions. Whoever wins the upcoming US presidential election, members of Congress may want to consider these issues prior to the end of the current Congress.

Political obligation

President Joe Biden has long been viewed as one of the most powerful American political elites with respect to foreign policy. During the Obama administration, James Taub argued that “Biden is the most powerful vice-president [on foreign policy] in history save for his immediate predecessor, Dick Cheney.” During the 2020 presidential campaign, Senator Joe Biden was viewed as someone who could “come into office with a resume that’s unmatched on foreign policy experience”. He also walked the walk. Biden made it clear that he would be committed to charting a fundamentally different course for American foreign policy if elected to office. At the time, he explicitly noted that this would require making sure that American foreign policy was “backed by clear goals and sound strategies”.

When Biden defeated Trump, few expected his administration to “solve the world’s ills on day one”. But many expected that the Biden administration would “start making significant moves right away to stitch the world back together”. In plain language, there was an expectation that the Biden administration would fix American foreign policy. As it turned out, one of those significant moves was making a commitment to “truth, transparency, and accountability” in American foreign policy. On the basis of the public record, it therefore seems reasonable to argue that the Biden administration has had an obligation to make moves to address known issues with the executive leadership and public strategic planning of US diplomatic missions from Day One.

Perennial problems

Prior to the start of the Biden administration, it was known that a lack of strong executive leadership was a perennial challenge for the implementation of American foreign policy by US diplomatic missions. Prior scholarship has shown that there is a tendency for US presidential administrations to fail to submit their nominations for key national security and foreign policy positions in a reasonable period of time. This includes ambassador appointments. According to practitioners, it is widely acknowledged that the nomination and confirmation process for ambassadors is dysfunctional.

Furthermore, it was known that the low quality of strategic planning is a perennial challenge for the implementation of American foreign policy by US diplomatic missions. Prior scholarship has shown that there is not only a tendency for US diplomatic missions to treat the production of their country-level strategic plans as nothing more than “paperwork exercises”. The public versions of these country-level strategic plans are often riddled with data quality issues, such as ambiguity, inaccuracy, inconsistency, incompleteness, misalignment, and out-of-dateness.

Executive leadership

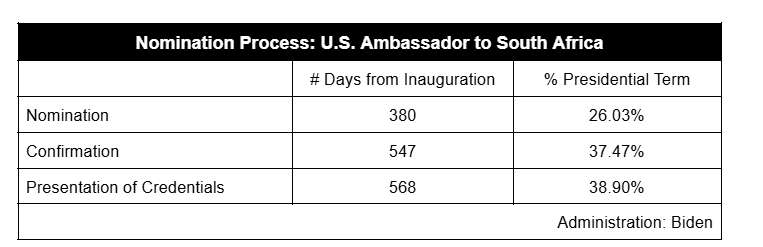

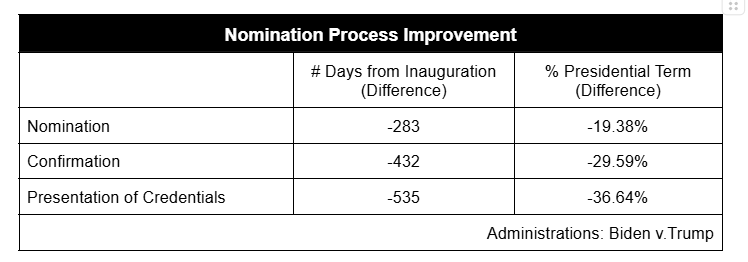

A rapid review of primary and secondary sources shows that the Biden administration may have performed better than the Trump administration when it comes to filling the post-inauguration vacancy of the US ambassador to South Africa. But there was still a long latency in the processes from the nomination to presentation of credentials of its new ambassador.

Biden administration

The Biden administration failed to nominate its US ambassador to South Africa until 380 days into its four-year term. Then, it took more than another 167 days for its pick to get confirmed by the US Senate. In the end, ambassador Reuben Brigety did not present his credentials to the South African government until 568 days into its term in office.

Trump administration

The Trump administration performed even worse. It failed to nominate its US ambassador to South Africa until 663 days into its four-year term.Then, it took another 316 days for its pick to get confirmed by the US Senate. In the end, ambassador Lana Marks did not present her credentials to the South African government until 1,103 days into its term of office.

Strategic planning

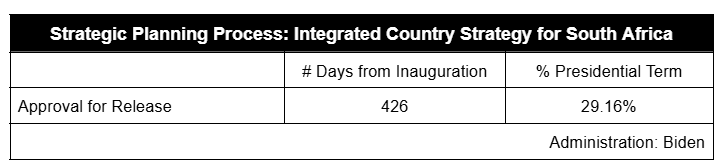

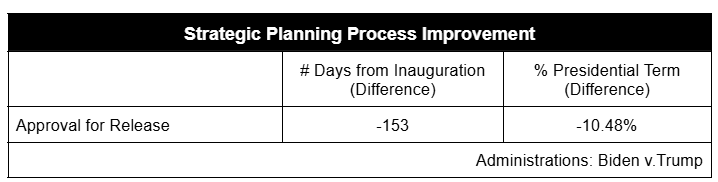

A rapid review of primary sources shows that the Biden administration performed better than the Trump administration on having the US Mission to South Africa produce a public country-level strategic plan following the inauguration. But there was still a long latency in its production.

Biden administration

The Biden administration failed to publish a public country-level strategic plan for the US Mission to South Africa until more than a year after the inauguration. Ultimately, it took 426 days before the Integrated Country Strategy for South Africa was approved for release. By that point, the Biden administration was more than a quarter of the way through its term in office.

Trump administration

Again, the Trump administration performed even worse. It failed to publish a public country-level strategic plan for the US Mission to South Africa until more than a year and a half after the inauguration. Ultimately, it took 579 days before the Integrated Country Strategy for South Africa was approved for release. By that point, the Trump administration was almost two-fifths of its way through its term in office.

Why It matters

A rapid review of the scholarly literature suggests that the failure of the Biden administration to fix these perennial challenges matters to American foreign policy. This is because it has likely had a negative effect on the performance and accountability of the US Mission to South Africa, including the mission’s accountability to the US Congress and, ultimately, the American people. Among other things, those are problematic states of affairs because they weaken the validity of the claim to political authority for country-level foreign policy by the US Mission to South Africa.

Performance of American foreign policy

A rapid review of the scholarly literature suggests that US diplomatic missions that have weak executive leadership are likely to be less effective and efficient at implementing American foreign policy than US diplomatic missions that have strong executive leadership. Prior scholars have shown that transformational leadership can influence the performance of subordinates, an executive leader can influence the performance of an organisation, and management systems can be used to increase the performance of an organisation. In reviews of empirical studies, scholars have shown that organisational leadership can have an effect on organisational performance.

To cite a couple of examples, Robert Hogan and Robert Kaiser showed that good leadership produces “effective team and good performance” by way of a review of the scholarly literature, while Bruce Avolio et al showed that “leadership interventions produced a 66% probability of achieving a positive outcome versus a 50–50 random effect for treatment participants” by way of a meta-analytic review of the scholarly literature on leadership impact studies. Given these findings, it is not surprising that many scholars assume that strong leadership is a key determinant of whether organisations “survive and prosper in today’s turbulent, uncertain environment”. It is reasonable to extend this assumption to US diplomatic missions.

A rapid review of the scholarly literature also suggests that US diplomatic missions that have low quality public country-level strategic plans are likely to perform worse at implementing American foreign policy than US diplomatic missions that have high quality ones. Prior scholars have long argued that strategic planning produces better outcomes than “haphazard guesswork” or “trial-and-error learning”. From a theoretical perspective, they predict that successful organisations will not only “anticipate and address environmental turbulence through strategic planning”. They will be successful by maintaining “flexibility in strategically planning decision options about how they will adapt when the environment changes, in a preparatory or ‘ex-ante’ state”.

Through empirical research, John Rudd et al showed that there is a significant correlation between strategic planning and organisational performance once one takes into account the mediating factor of flexibility in strategic planning. Separately, Peter Brews and Michelle Hunt found that high quality strategic plans are more likely to result in better outcomes regardless of the operating environment in their analysis of the planning practices of 676 firms. In reviews of empirical studies, scholars have suggested that the quality of strategic planning matters for organisational performance. To cite an example, Chet Miller and Laura Cardinal found that “strategic planning positively influences firm performance”, with “methods factors primarily responsible for the inconsistencies reported in the literature”, in their famous synthesis of two decades of empirical research. Given these findings, it is not surprising that many scholars assume that strategic planning has a significant effect on “the organisation’s ability to survive.”

Accountability to Americans

The US department of state declares that one of the purposes of the public country-level strategic plans is to help the US government “provide greater accountability to its primary stakeholders and the American people”. Prior scholars have argued that four questions need to be asked whenever one seeks to make sense of government accountability: 1) Who is the actor responsible for rendering the account; 2) To whom are they responsible for rendering the account; 3) What are they responsible for rendering the account; and 4) Why does the actor feel compelled to render the account?

Some of the answers to these questions appear obvious in the context of a US diplomatic mission. Among other things, it is clear that the US secretary of state has the legal responsibility to render an account of the implementation of American foreign policy by US diplomatic missions to the US Congress. But the current legal framework does not provide much granularity on what the US secretary of state is responsible for rendering in their account.

Per 10 USC §113, the US secretary of defence has the legal responsibility to provide the congressional defence committees with an annual summary of their “priority posture initiatives” of the commanders of the geographic combatant commands. Per 22 USC §2656 or elsewhere, the US secretary of state has no similar statutory requirement to provide congressional foreign policy committees with an annual statement of the priority mission initiatives of the chiefs of the diplomatic missions. That is why 18 FAM 301.2 is so important. It sets the standards for what the chiefs of mission are responsible for rendering in their accounts to institutions of answerability and enforcement (for example, National Security Council and the US Congress).

With respect to these standards of assessment, a rapid review of the scholarly literature suggests that US diplomatic missions that produce low quality strategic plans are likely to be less accountable to the American people than US diplomatic missions that produce high quality strategic plans. Prior scholars have not only argued that an important distinction needs to be drawn between transparency of standards, answerability for actions, and enforcement of standards on the grounds that transparency of standards is not a sufficient condition for the achievement of organisational accountability.

They have also argued that an important distinction needs to be drawn between the quality and quantity of transparency of standards and answerability for actions. To cite some examples, Alasdair Roberts showed that redacted information has a significant negative effect on government accountability, David Heald revealed that the direction and variety of transparency can have a significant effect on the quality of the valued objects that are achieved, and Archon Fung et al found that the relationship between targeted transparency and transparency effectiveness is significantly affected by the degree to which the former is user-centric and sustainable.

Given these findings, it is not surprising that many scholars not only assume that the quality of strategic planning has a significant effect on the degree of organisational success. They also assume that it has a significant effect on organisational accountability. It is reasonable to extend this assumption to the public country-level strategic plans of US diplomatic missions.

The common good

Prior scholars have long argued that low-quality government institutions have a significant negative effect on the service of governments to the common good. To cite a couple of examples, Janine Wedel showed that shadow elites can effectively undermine the service of governments to the common good by undermining the “rules of accountability and business codes of competition”, while Thuy Mellor and Jak Jabes argued that the openness, accountability and responsiveness to the community of government institutions has a significant effect on their service to the common good. If one accepts the normative argument that “state had no other purpose than to serve the common good”, then the failure of US diplomatic missions presents a serious problem for the US government. It effectively undermines the validity of its claim of political authority over foreign affairs. The US Congress may therefore want to consider these perennial issues with strategic management at US diplomatic missions before the next presidential administration comes into office in a few months.

Michael Walsh is an affiliated researcher at the Georgetown School of Foreign Service and a visiting researcher at Ludwig Maximilian University of Munich. This commentary presents preliminary findings from his current research project.